'Sarasota works hard to keep unpleasantness, whether real or imagined, hidden from view'

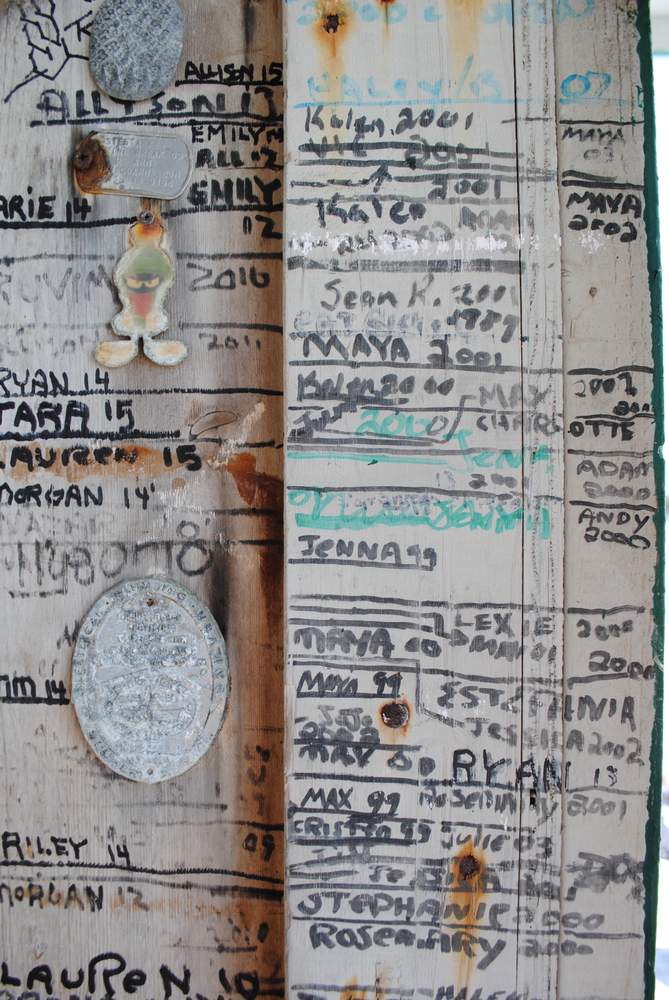

“It’s all part of the experience. I’m part of the experience too. The parasail [ride-selling] guys, the free-taxi drivers who make every single person feel they are welcome. One kind person or one great conversation and that will make you come back.”

He makes no attempt to dislodge Buggy, a homeless man who has spent the night underneath his watchtower. “Guys like him come and go,” says Scoot. “Why would I chase him away? We have plenty of facilities in our park system and guys like him can do alright if they maintain a low profile.”

Buggy not only looks like Brad Pitt: there is even a touch of radical Hollywood in his politics.

“It’s not the homeless who are the problem but the system,” declares the 25-year-old, born to middle-class parents as Robert Baker. “We’re all enslaved to the dollar, a piece of paper that means nothing.”

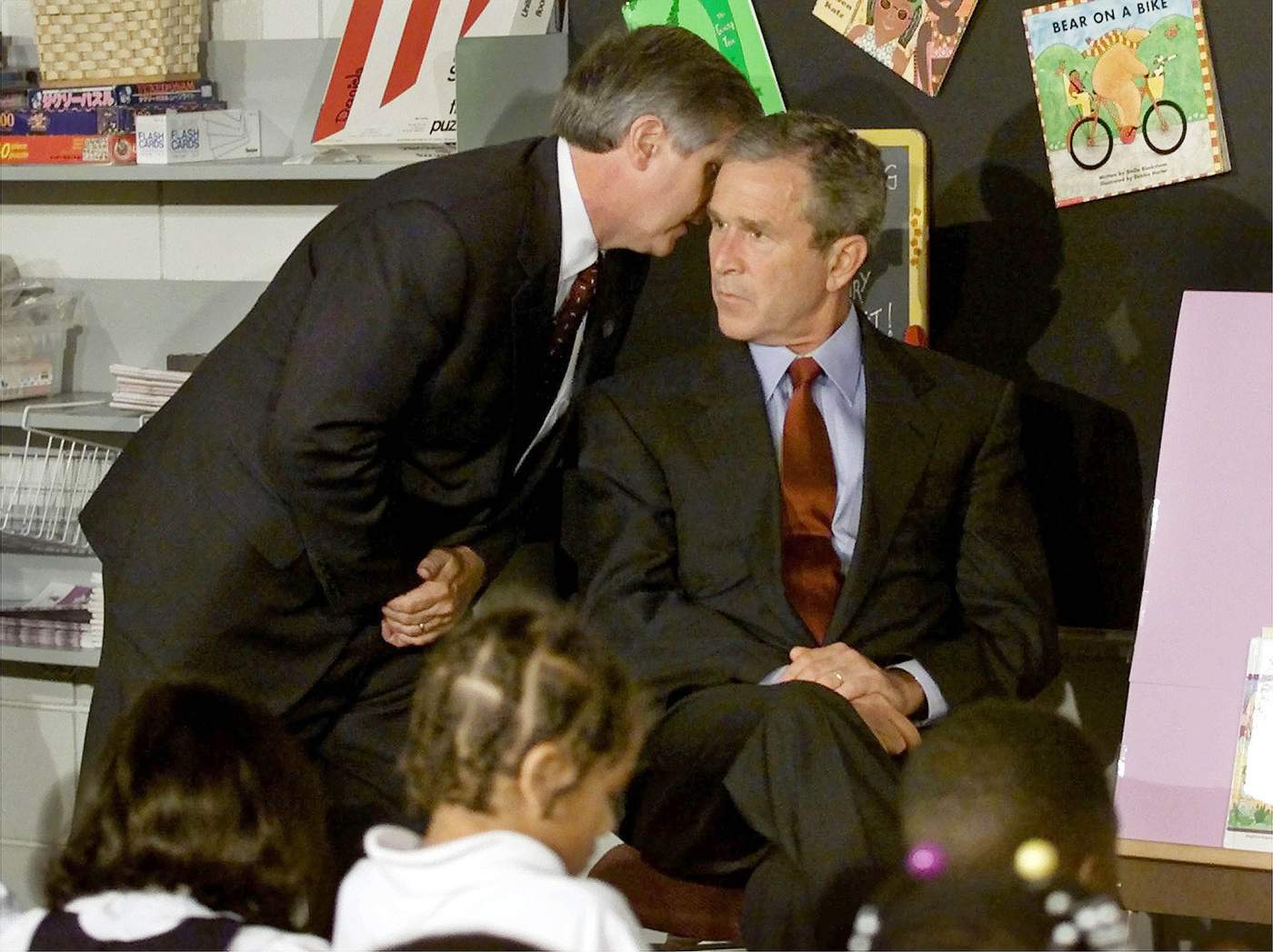

At the McDonald's on US 41, Sarasota’s first female police chief hands out her card and stresses the importance of talking to all communities — including Newtown.

Chatting at a “coffee with the cops” advertised on Twitter, Bernadette DiPino says that the murdered tourists had “wandered into a high-crime area”. Yet the charismatic police chief maintains that matters have improved in Newtown since she took over almost three years ago: “We are hitting big drug dealers because gang activity attracts violent crime.”

In line with her belief in “smarter policing”, she has also been meeting the families of young people arrested for drug-dealing and deciding, in some cases, to defer charges “so they don’t go to jail and learn even worse things”.

“When you … partner with the community as your eyes and ears, that reduces the need for policing,” says this practising Catholic. She argues for example that priests are ideally placed to persuade illegal immigrants to come forward as witnesses to crimes in return for not being questioned on their immigration status.

One of Chief DiPino's subordinates, Chris O’Donnell, is in no doubt that an officer suspended in south Carolina for shooting a black man seven times in the back a few days earlier, is guilty.

Yet he disagrees with the notion that gun control laws of the kind supported by President Obama would help curb America’s violent crime including a spate of mass shootings.

“The media portray us as a bunch of cowboys,” says the policeman, “but there is nothing further from the truth. Granted there may be one per cent of [police who are] and we should get rid of them.”

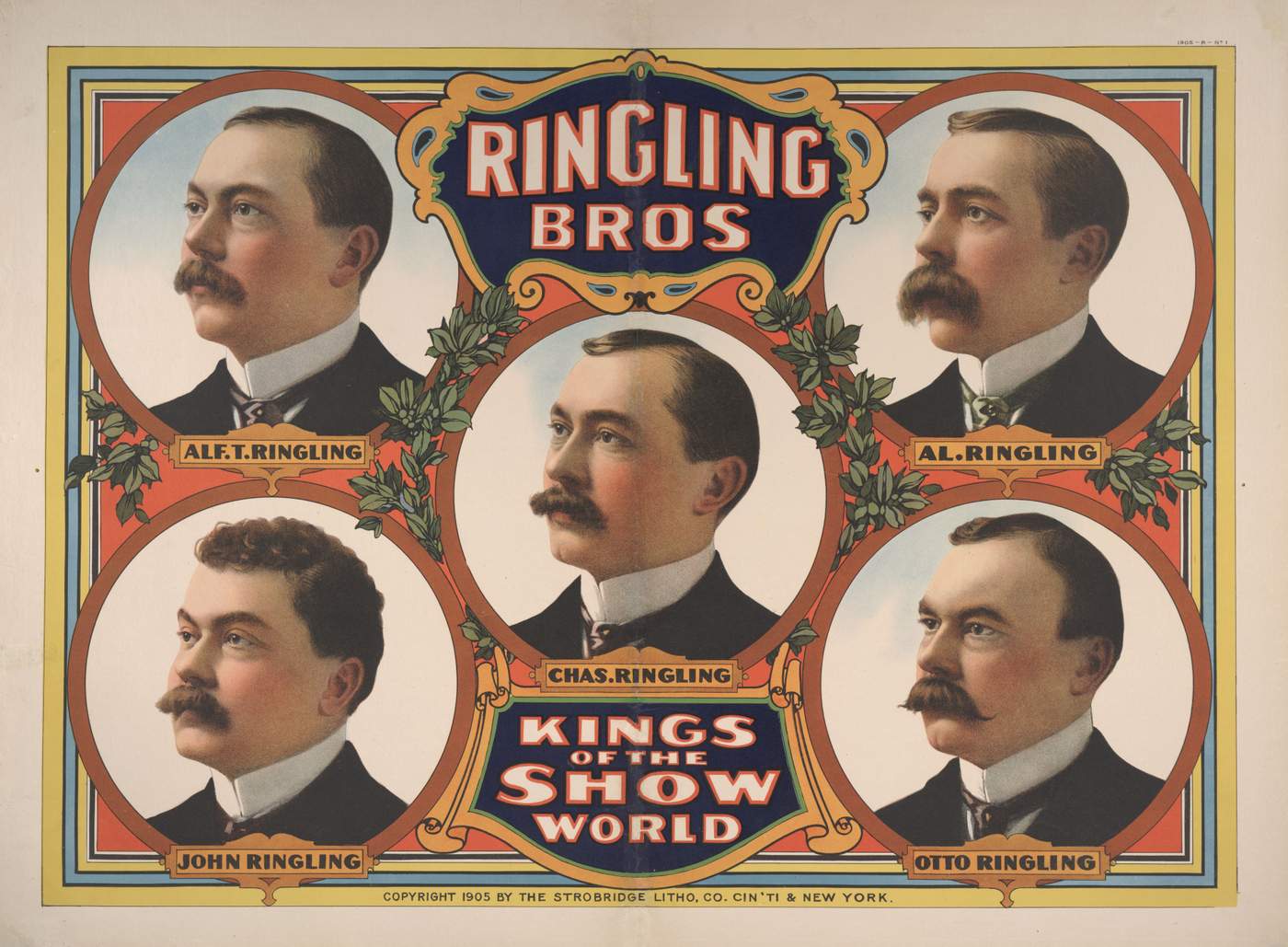

Long-term residents fret at the gradual disappearance of charming vestiges of old Florida — at the hands of the same developers satirised in Carl Hiaasen’s novels.

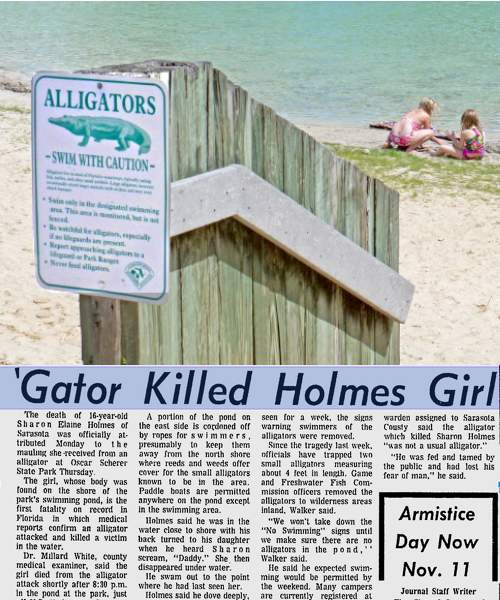

We’re destroying the environment with our own hands,” says guide Todd Terrill. “In 50 years we’ll have to go the zoo to see alligators and deer.”

Credits

Photography by Alexandra Boulton, Detlev von Kessel, John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art Tibbals Digital Collection, Reuters

Videography by Detlev von Kessel

Research by Charlie Mitchell

Design by Kari-Ruth Pedersen

Produced by Ruth Lewis-Coste

Edited by Helen Barrett

Video editing by Charlie Bibby

Picture editing by Andy Mears

Built with Shorthand