Dawlen Tirkey, a nurse in one of India’s poorest and least developed states, had decided that she and her husband could afford to have just one child.

Their son, Abhinaw, was born in an uncomplicated home delivery in 2006 in the small town of Bero in the state of Jharkhand. But Tirkey yearned for a daughter and so, when the couple’s finances improved, they decided to try for a second baby.

At the age of 34, Tirkey gave birth to a girl in a private hospital in the state capital of Ranchi. Elated, she named her Abhilasha — “wish” or “desire” in Hindi.

Dawlen Tirkey's husband, Manoj, and their son, Abhinaw

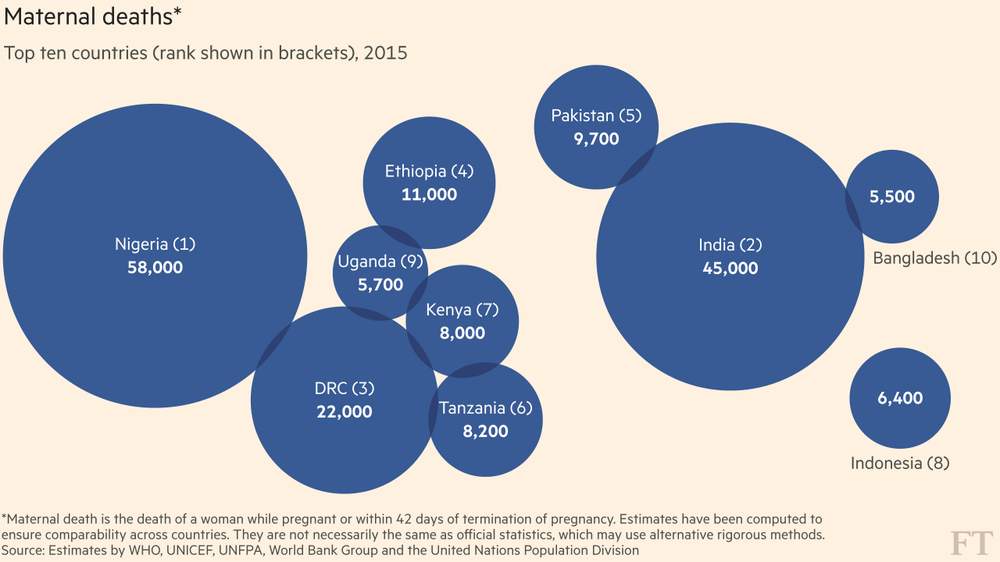

Her happiness was short lived. Fewer than 12 hours later, Tirkey was dead, one of the estimated 45,000 women to die in, or soon after, childbirth or from related causes in India last year.

“I was hoping she would be OK, like in the movies, where we see people coming back to life again after dying,” says her husband, Manoj Khalko. “But it didn’t work that way.”

Until recently, most Indian women — especially in rural areas — gave birth at home, attended by traditional village midwives.

But, in 2005, the government began handing out cash incentives (the equivalent of about $20) for women to give birth in “institutional settings”, mostly government clinics. It was a bid to stem the numbers of maternal and infant deaths, which in absolute numbers are the worst in the world.

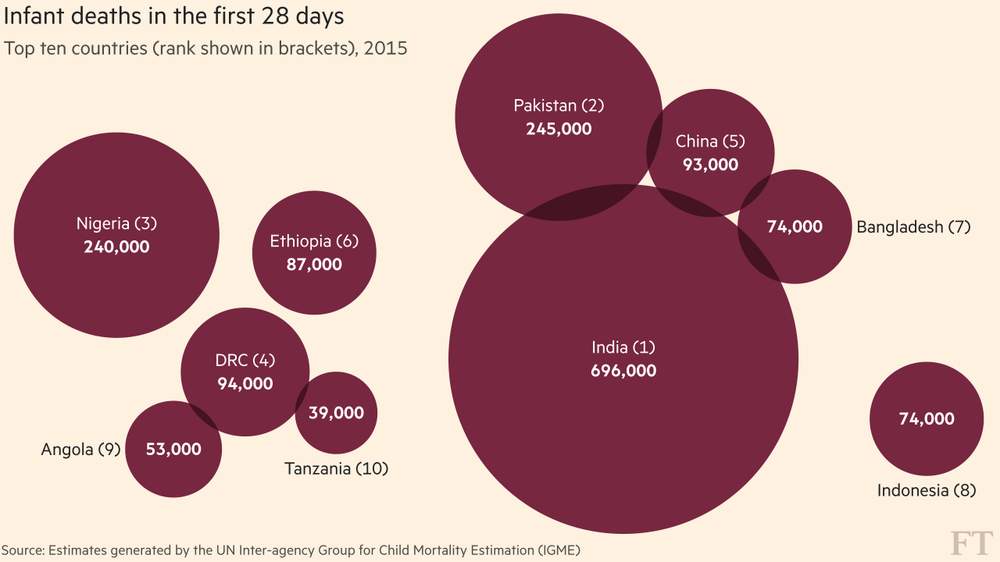

India ranks first in the world for number of newborn deaths

Today, public health officials say that nearly 70 per cent of Indian babies are born in some type of medical facility, but the underfunded public health system is struggling to cope with a rush of new patients.

Private clinics are springing up to meet the extra demand, but they are largely unregulated.

While the number of maternal deaths has fallen in recent years, the drop has not been nearly as sharp as policymakers hoped.

“Earlier, deaths were occurring at home. Now they are occurring between facilities,” says Dr Suranjeen Pallipamula, a Jharkhand-based maternal health expert with India’s Public Health Resource Network.

“People are coming to the first facility. Then, for a complication, they are being referred to a second facility, and they are dying between facility one and facility two.”

As a nurse, Tirkey was well aware of the potential dangers in giving birth in a poorly staffed or under-equipped facility. So when she went into labour on a Saturday evening in August 2015, it was with some reluctance that she checked into her local state-run health centre, across the street from her home.

The clinic is intended to be a small but fully functioning hospital serving the town and surrounding villages — a catchment area of more than 177,000 people. Staff say it is meant to have 10 doctors, including specialists in obstetrics and gynaecology and an anaesthetist, as well as 19 highly-trained nurses. But the reality is different.

The state-run Community Health Centre in Bero, Jharkhand

There are currently just six physicians, none of them specialists, and two senior nurses. A rudimentary operating theatre stands unused. There is no blood bank. Women with any kind of birth complication — whether an obstructed labour requiring a Caesarean section or severe bleeding necessitating a blood transfusion — must be referred to a better-equipped hospital.

Blood tests had already revealed that Tirkey was mildly anaemic — a pervasive problem among Indian women, which stems from poor nutrition and raises the risk of shock from postpartum bleeding.

Khalko, a clerk in a state school, tried to reassure his wife, but when he visited her on Sunday, the day after she had checked in, she was still in the early stages of labour and insisted on being transferred to another hospital.

While at the clinic, she had witnessed a baby die during an obstructed labour after its mother rejected the doctors’ advice to transfer for an emergency delivery. “The baby was stuck. It couldn’t come out,” says Khalko. “Somehow they delivered the child. But she saw it die.”

So Khalko obtained a referral for his wife, which made the couple eligible for a free ride into Ranchi, under a state scheme to provide women in labour with free transportation to healthcare facilities.

The Rajendra Institute of Medical Sciences, a large public hospital

Usually, rural clinics refer patients to hospitals such as the free and well-equipped Rajendra Institute of Medical Sciences (otherwise known as Rims) in Ranchi, where demand is so high that women sometimes lie two to a bed during labour, or on mattresses in a corridor during post-delivery observation.

In spite of the overcrowding, Rims can and does save lives. But Tirkey and Khalko ended up somewhere else. The driver of their free ambulance, who was by chance an old classmate of Khalko’s, urged the couple to try a private hospital called City Trust.

Despite her mother’s death, Abhilasha is thriving. She now lives in Lohardaga, a town 75km from Ranchi, with her maternal grandmother and aunt, Savita Tigga, a nurse married to Tirkey’s brother.

Tigga had been trying to have a baby for years when Abhilasha came to live with them.

“They’re raising her as their own baby,” says Khalko. “They are not from outside, they are members of the family. So I feel my daughter is still with me.”

Luz Betsaida Orozco Pineda stands in the doorway of her mother-in-law’s house in Juchitán de Zaragoza, Mexico. She is 14 years old.

The house, which doubles as the local grocery store, is in a new neighbourhood known as 6 de Noviembre, on the outskirts of the town in the southern state of Oaxaca.

Orozco’s young life has been shaped by the ancient indigenous customs of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. At 13 she was “stolen” from her father’s house by her boyfriend and taken to live with his family.

To western ears, the verb sounds violent, but it is a term used commonly by locals to describe a marriage ritual of the indigenous Zapotec people.

While Mexico has outlawed marriage under the age of 18, many young girls become unofficial wives and mothers much earlier.

In Juchitán, teenage pregnancy is expected, even prized.

The five-week-old baby Orozco now cradles in her arms, José Miguel, was born in January 2016.

Orozco sees him as an escape from a strict father, who banned her from going to the park or to parties like other teenagers, little knowing she had been seeing a local boy in secret since the age of 10.

The custom of “stealing” a bride is an ancient one and carries no social stigma, although it is often considered a lower-class tradition. Orozco says she was stolen — robada in Spanish — but sometimes the term novia huida or “runaway bride” is used interchangeably, underscoring the fact that under-age girls often view marriage as a path to freedom.

When Orozco arrived at the home of her in-laws, her relationship was consummated and, according to custom, her virginity was proved to the waiting family with a blood-stained cloth, proudly put on display and adorned with rose petals.

Surrendering what few vague dreams she had for her future, Orozco became one of the half a million adolescent Mexicans who get pregnant every year.

Mexico has by far the highest teenage pregnancy rate in the OECD — more than four times the average of this club of rich and upwardly mobile countries. Half of all sexually active teenage girls in Mexico have been pregnant, according to Marie Stopes, a family-planning organisation campaigning to reverse the trend.

There are two main reasons. First, many girls are either too shy to ask for the free contraception that is available on the national health service, unable to buy it elsewhere or simply ignorant of its existence.

Second, when teenage girls do become pregnant they have few options. As in most Latin American countries, the majority of Mexican women have no access to abortion. It is legal only in Mexico City and in a handful of exceptional cases elsewhere in the country.

Backstreet abortions are the fourth-biggest cause of maternal mortality in Mexico and one of the main causes of death in 15 to 19 year-olds is complications from pregnancy.

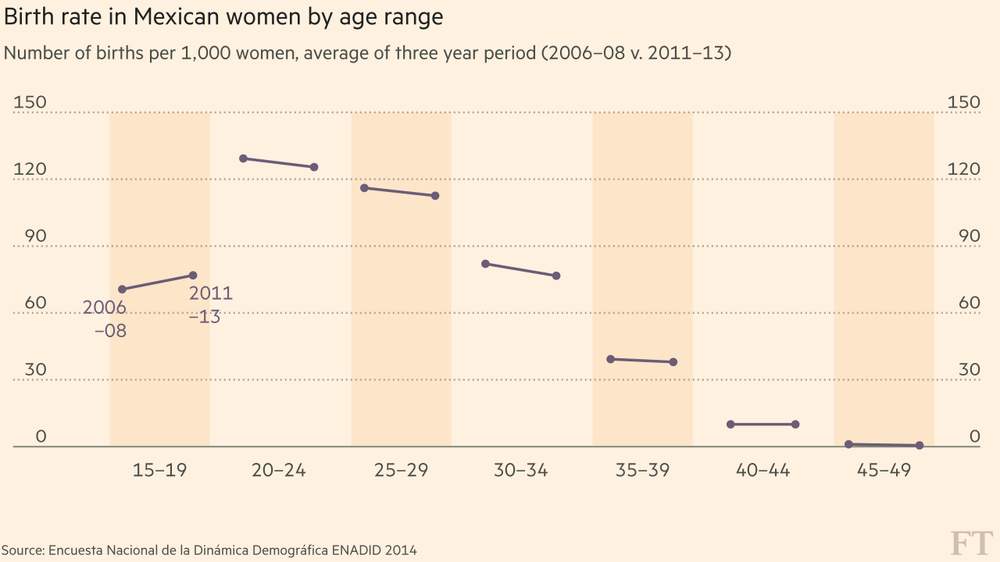

Teenagers are the only group whose fertility rates rose between 2006–13

The statistics have pushed Mexican officials into action. In January 2015, the government launched a national campaign to promote sex education.

Enrique Peña Nieto, Mexico’s president, wants to halve the birth rate in 15 to 19-year-olds by 2030 and eradicate it completely in under-14s. This will be a tall order: in 2013, there were 11,300 mothers aged between 10 and 14, according to government statistics.

“We have to … eradicate macho culture,” Peña Nieto said at the campaign launch.

Machismo is entrenched in Mexican society. In Mexican slang, when something is great, it is called padre, the word for father. Conversely, if something is worthless, Mexicans say, Me vale madre, literally “It is worth a mother to me”.

Contraception never crossed Orozco’s mind: “Once I got married, I talked to my husband and said I wanted to have a baby. He said, ‘Me too. If you want to, let’s’.”

Luz Orozco explains why she wanted to have a baby at 14

After she has observed the traditional 40-day quarantine period, when new mothers are confined to the house with covered heads in an effort to prevent illness, Orozco will begin her new role as housewife. But, like many of her friends, she dropped out of school when she moved in with her new family.

“If your mother-in-law says you can still go to school, you can go. But some say no because you might meet a boy you like more,” she says. “I wanted to carry on studying but they wouldn’t let me.”

Seventeen-year-old Xochiquetzal Sánchez Escobar is an exception. The eldest of three siblings, she lives in the more upmarket town of El Espinal, near Juchitán, with her mother and other relatives.

She is expecting a baby in June, but plans to be back in class for the start of her final year of secondary school in September.

Xochi, as Sánchez is known, looks every inch the teenage rebel, with dyed hair, elaborate piercings and tattoos. She always wanted to have a baby at a young age, but it was her 24-year-old partner Rubén Zárate Albino’s idea to try.

Xochi Sanchez worries she may have complications with her labour

MexFam, an affiliate of the International Planned Parenthood Federation, is trying to change the way young girls think. Its social workers educate adolescents about the need to protect against both sexually transmitted disease and pregnancy, and recommend using condoms together with other methods.

“If we can’t reduce the risk of sexually transmitted disease, we can reduce the risk of pregnancy,” says José Javier Jiménez Cruz, the director of MexFam’s local clinic.

But it is an uphill struggle. One of MexFam’s workshops in the area was run by a 17-year-old who ended up pregnant herself.

Luz Selena Pineda Juan, who lives in a working-class district of Juchitán, turned 16 in February and is due to give birth in April.

When her boyfriend, a married man who she says is getting a divorce, asked if he should use a condom, she said no. “I can just take the morning-after pill,” she said.

She can’t remember the number of times she has taken emergency contraception, which consists of two pills usually taken 12 hours apart, “but it was several”.

She used to scoff at the stupidity of girls at school who got pregnant. “I didn’t think it would happen to me,” she says. “If I’m using contraception, there’s nothing to worry about. But, well, I slipped up.”

Back in 6 de Noviembre, Orozco says that having her baby has offered her a measure of freedom, albeit limited.

She has struggled with the broken sleep and dirty nappies, but she has no regrets. In a region where many girls become mothers and separate from their partners before their mid-teens, she is confident that hers is a union that will last.

“I wanted to leave home, to discover,” she says with childlike directness. “If I get married, I can go out, even if it is with my husband, but I can go out.”

HIV is just one of many preventable infections that threaten mothers and children in DRC, a country that ranks among the worst in the world for maternal deaths in childbirth and infant mortality.

With a population of around 70m, that makes the country a significant contributor to the global tally of preventable illness and death each year.

“Everything is a big challenge,” says Dr Mukengeshayi Kupa, the secretary-general of DRC’s ministry of public health. He says just 5 per cent of government spending is on health.

“It is very difficult to convince the government to put more in compared with mining or agriculture, where you see the results,” he says. “Health is not very visible.”

DRC ranks third in the world for maternal deaths

When she finally decided to take action, Hutu came to the Centre Hospitalier de Kabinda in Kinshasa, run by the aid group Médecins Sans Frontières.

The unit is exceptional in many ways, not least because it offers free assistance to tackle a range of preventable diseases. Its wards are filled with patients who have infections such as tuberculosis, meningitis and respiratory problems, caused by late-stage HIV.

The Centre Hospitalier de Kabinda in Kinshasa does not charge fees

Stigma remains a hurdle to treatment. Hutu is not the only patient reluctant to acknowledge her diagnosis. “Lots of people arrive in a very bad way,” says Sofie Spiers, one of the doctors at the clinic.

“Most are women, not only because they are more vulnerable to infection, but also because their male partners tend to avoid the taboo around HIV by staying away from hospital and instead dying at home.”

In a poorly educated society with institutions constrained by lack of funding, the problems start with pregnancies in girls as young as 13. At this stage, childbirth brings a higher risk of complications and cuts women off from education.

Understanding of family planning is limited: fertility has risen from an average of 6.3 children per woman in 2007 to to 6.6 in 2013-14.

“Children are seen as wealth,” says Gaby Kasongo, reproductive health manager at PSI, a non-governmental organisation that offers family planning. “DRC is pro-natalist. There is pressure from our elders. I have three children and my in-laws and my own mother say I have not done enough.”

Medical staff and pharmacists sometimes send adolescents home empty-handed when they seek contraception, telling them they need parental permission, she adds. Under a colonial-era law, up for revision only now, half a century after independence, wives are not supposed to receive contraception without the approval of their husbands.

How can we reduce unnecessary maternal and child deaths?

Submit innovative projects with proven impact to the FT/IFC awards by April 7: details here

Credits:

India

Amy Kazmin, reporting

Suzanne Lee, photography and video

Mexico

Jude Webber, reporting

Bénédicte Desrus, photography

Cinthya Chávez, video

Democratic Republic of Congo

Andrew Jack, reporting

Charlie Bibby, photography and video

Editing and Production

Edited by Cordelia Jenkins

Graphics by Chris Campbell

Production by Ruth Lewis-Coste, George Kyriakos, Jearelle Wolhuter and Kari-Ruth Pedersen

Built with Shorthand

All editorial content in this report is created by the FT. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded our reporting but had no prior sight of the content.