Good news reader! It is the first day of 2020 and the FT has gifted you $100 to track the US stock market. If you had used that money to follow the S&P 500 index in the past, the average gain would have been about $10.50 a year in the last five years. Let's see how 2020 shapes up.

Follow $100 through 2020

Early January gives few clues of what lies ahead. US stocks hit a record high. Big topics are global trade and Brexit.

On January 10 you read China has announced 59 cases of a new coronavirus, or Sars-like, disease. Both the World Health Organization and the Chinese authorities say it “does not transmit readily between people”.

By January 23, investors and analysts are getting jumpy.

It’s important that we don’t panic... but really look to history as a guide,” says Kristina Hooper, chief global market strategist at Invesco.

JPMorgan notes that markets have often dipped only slightly and rebounded swiftly from other virus outbreaks.

You end the month having lost all your early gains.

Even now, the expected impact of coronavirus globally is mild, though Chinese stocks provide a warning, dropping 9 per cent on February 3 — the biggest fall in nearly 13 years.

But markets recover swiftly at the beginning of February, with some investors happy to have picked up bargains.

“It usually pays to buy when others are panicking,” says Trevor Greetham, head of multi asset at Royal London Asset Management.

Morgan Staney economists conclude the virus will “not derail the economic recovery”. In Asia, however, cities are locked down, and ports and factories are closed.

US equities set a record once again.

But the resilience in stocks is starting to unnerve some markets veterans.

“I have never in my career seen anything as crazy as what's going on right now,” says Guggenheim’s Scott Minerd.

Then, the complacency snaps. The trigger: Italy. The country starts shutting down and cancelling events. Suddenly for investors in the US and Europe, the virus feels closer to home.

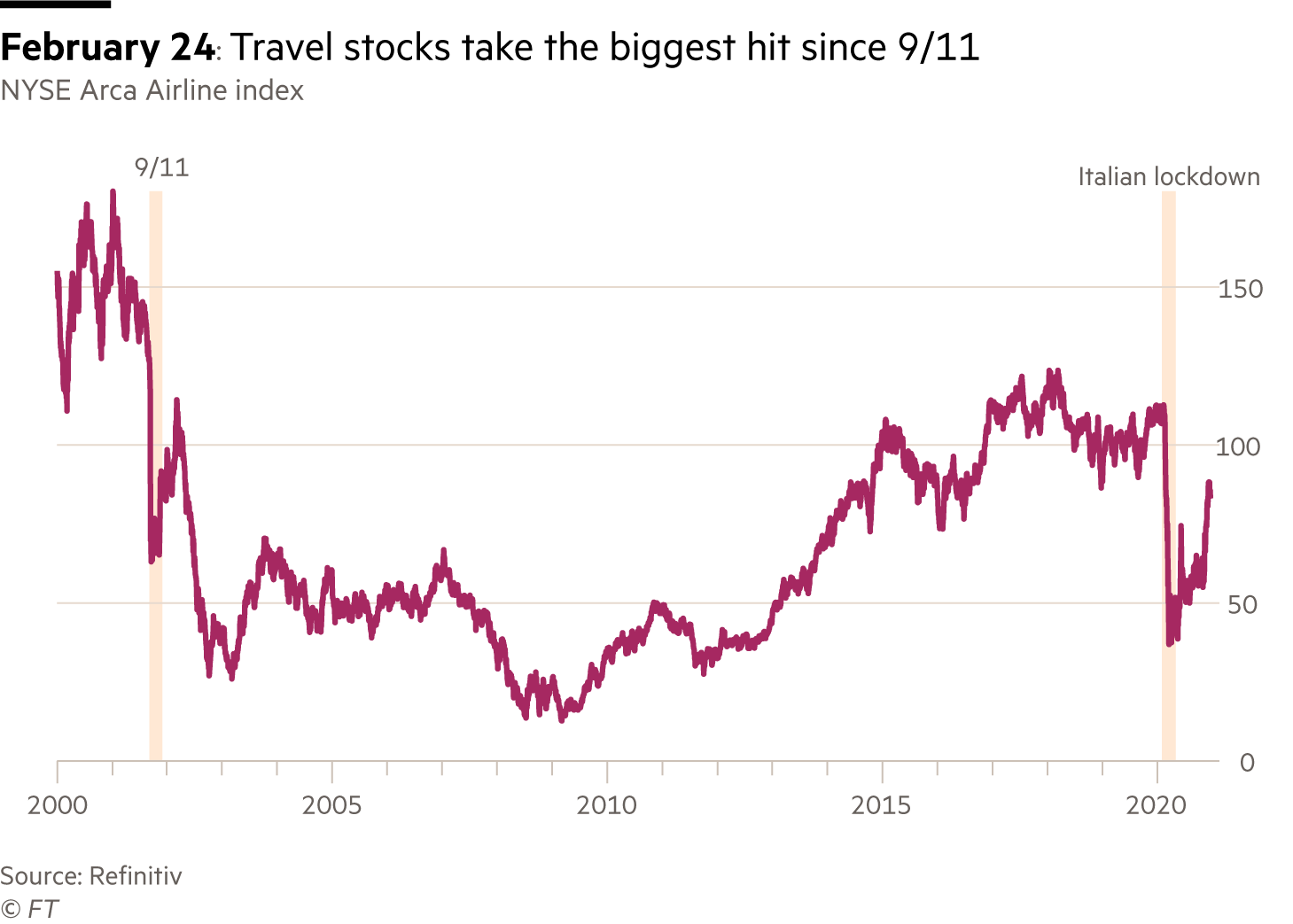

Stocks take the biggest dive since 2008. Travel stocks take the biggest hit since 9/11, and US government bonds start flying as investors scramble for safety.

The message from the White House: buy the dip. “Stock Market starting to look very good to me!” tweets Donald Trump.

It is not looking so good to investors, however. In one week, the S&P 500 tumbles 12 per cent, dropping into a correction — a more than 10 per cent fall from a recent high, putting your $100 at just $91.43.

As March starts, the tension builds. Banks and investors are preparing to send everyone, including traders, to work from home. No-one really knows if the trading infrastructure will cope. Finance ministers say they are ready for battle.

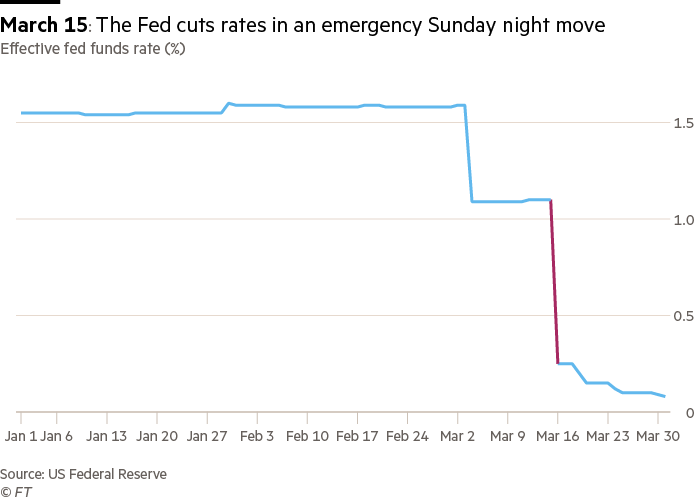

The central bank fightback begins. The US Federal Reserve announces a rare emergency rate cut. Normally that would boost your stock holdings. But this time, the stock markets are not buying it. The depth of concern is evident in the US government bond market, which is in hot demand, pushing prices so high that 10-year yields sink below 1 per cent for the first time.

The tone starts to get panicky.

It’s pure fear — you can see it in the empty supermarket shelves and you can see it in the bond market,” says Dickie Hodges, a fund manager at Nomura Asset Management, on March 6.

Just as fragility starts to build in both stocks and bonds, a curve ball arrives from the oil market, which has already dropped by a third since January after the virus hammered demand.

On March 9, oil crashes by 30 per cent within seconds — the biggest drop since the Gulf war in 1991 — after Saudi Arabia starts a price war with Russia.

Assets linked to crude oil come under pressure. European stocks sink into a bear market. Safe bonds, such as UK government debt, meet huge demand — UK yields drop below zero for the first time.

The S&P 500 suffers its worst day since the financial crisis in December 2008, plunging 7.6 per cent and triggering circuit breakers designed to smooth panicky trading — the first time they have been used since 1997.

“The market is in the process of pricing a global recession,” says Deutsche Bank.

On March 11, the Bank of England starts its offensive, with a “powerful” package of measures including an unscheduled rate cut — the first since 2008.

Again, the Fed acts, expanding its intervention in short-term lending markets for the second time in a week.

And again on March 12, the Fed pledges to pump trillions of dollars into the financial system. The European Central Bank also rolls out a package of measures.

But then comes a crucial mis-step. ECB president Christine Lagarde says the central bank is “not here to close spreads” in the bond market — taken as a hint that she will not support Italian debt at all costs. Italian bonds sustain the biggest fall on record. Ms Lagarde apologises three days later.

From here the pressure on stocks is relentless.

The S&P 500 suffers the worst day since the 1987 Black Monday market crash and you’ve lost nearly a quarter of your initial $100 investment.

Adding to the storm, Donald Trump announces a ban on flights from Europe.

This was the most expensive speech in history,” says Luca Paolini, chief strategist at Pictet Asset Management. “Investors are voting with their feet, and I don't blame them.”

By this point, daily double-digit declines in stock markets around the world have become the norm and corporate bonds become impossible to trade.

Then we hit the point of peak fear.

The reason: the government bond market.

US government bonds, or Treasuries, are ultra-safe assets that always rally when the going gets tough, helping to balance out portfolios when stocks are in trouble. It is one of the most reliable dynamics in finance.

But Treasuries first become hard to trade, and then start falling. Ordinary investors and savers want their money back out of markets, and fast. The firms that manage their money can’t keep up with demand.

Normally, traders can hop in and out of Treasuries easily but now the system struggles to cope. The market is “overwhelmed by liquidity concerns”, as Bank of America analysts put it.

“It’s just not functioning. It is freaking people out,” says Gregory Peters, a senior portfolio manager at PGIM Fixed Income.

The Fed acts yet again on March 15, with an emergency Sunday night move ahead of the market open, slashing rates to zero and pledging to buy bonds in huge volumes.

But it’s still not enough. Short-term lending markets are frozen, and stocks are in freefall.

The Fed keeps going, first supporting the overnight lending market and then committing to buying commercial paper, in a facility last wheeled out in the 2008 crisis. But we are in meltdown.

By March 18, the UK is preparing to go into lockdown, bonds are still sliding as investors dump anything they can.

At this point, your $100 has shrunk to just $73.61.

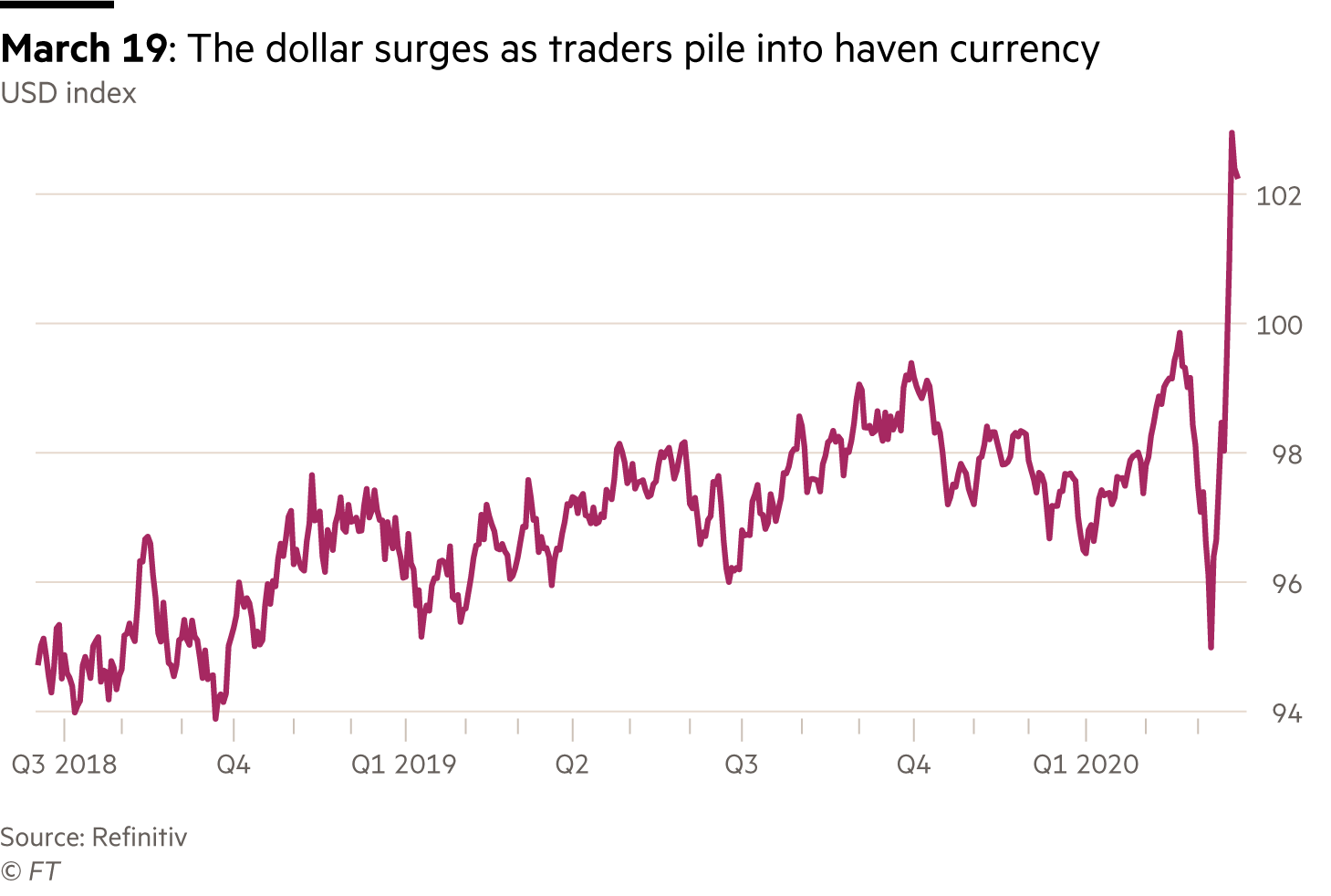

The pressure point now is the dollar. Companies and investors are rushing into the currency because it is considered the most stable in times of crisis. This result pressures most other currencies, such as sterling, the yen and the Australian dollar.

“We are seeing disorderly moves and forced selling as investors either liquidate positions or seek safety in US dollars,” says Claudio Piron, head of Asia rates and currency strategy at Bank of America Securities.

The newly-installed governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, says markets are “bordering on the disorderly”.

Yet again, the Fed steps in, expanding dollar swap lines with a range of other central banks to cool the runaway dollar, which is threatening to cause problems of its own for companies and countries around the world with outstanding debts in the currency.

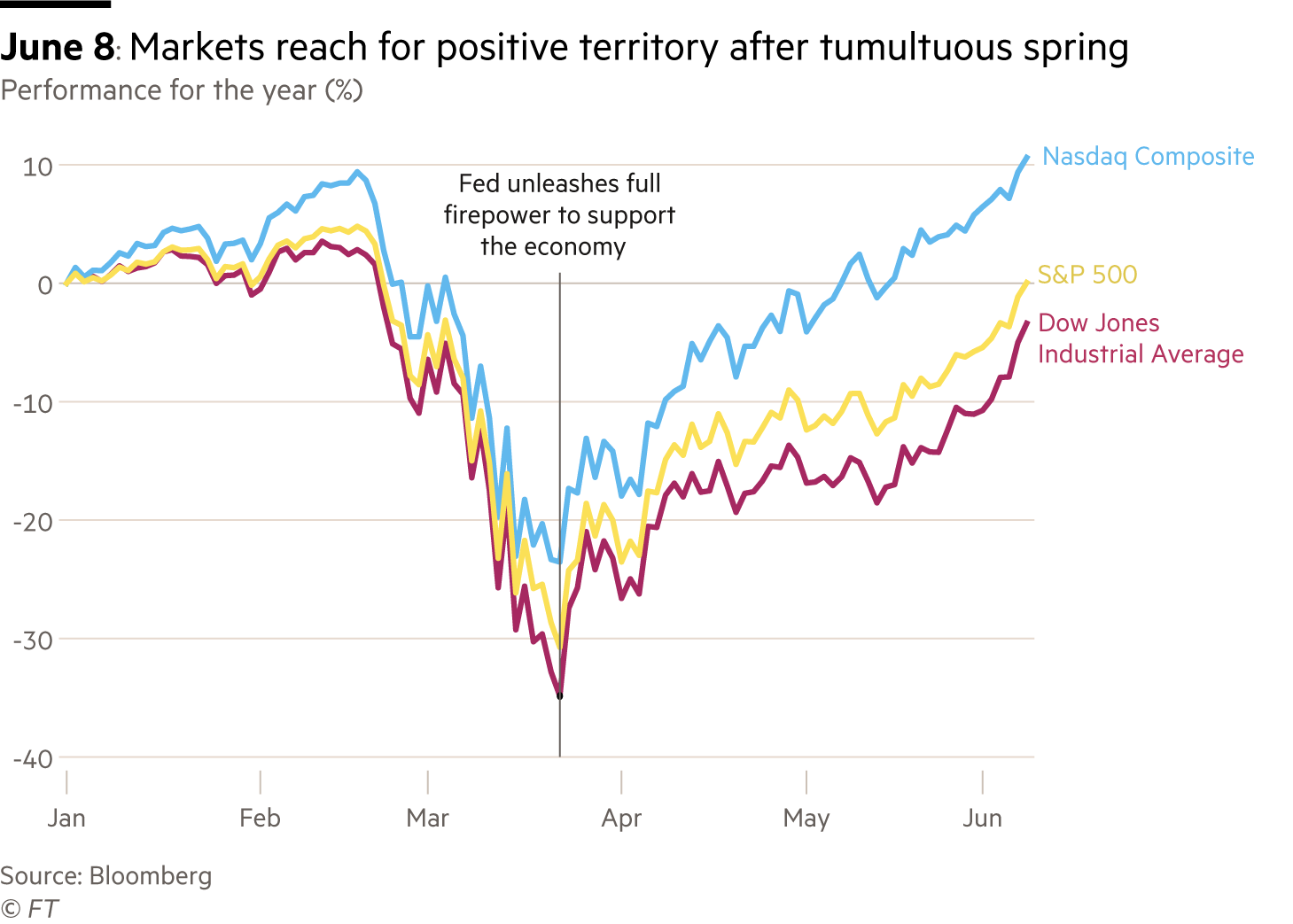

With equities and bonds collapsing, investors have nowhere to hide. Action is needed not just from central banks, but from governments too. This is most apparent on March 23, when the Fed promises to buy an unlimited amount of Treasuries — a stunning move — but traders fret that Congress will struggle to agree on fiscal stimulus.

“Fundamentally what the market is looking for is a very solid fiscal response,” says Anik Sen, global head of equities for PineBridge Investments. “If the main issue is businesses shutting down, then monetary policy from the Fed has limited efficacy.”

You have lost $31.32 from your initial investment in January.

Finally, by March 24, a break in the clouds. Congress passes a massive stimulus deal and stocks rebound.

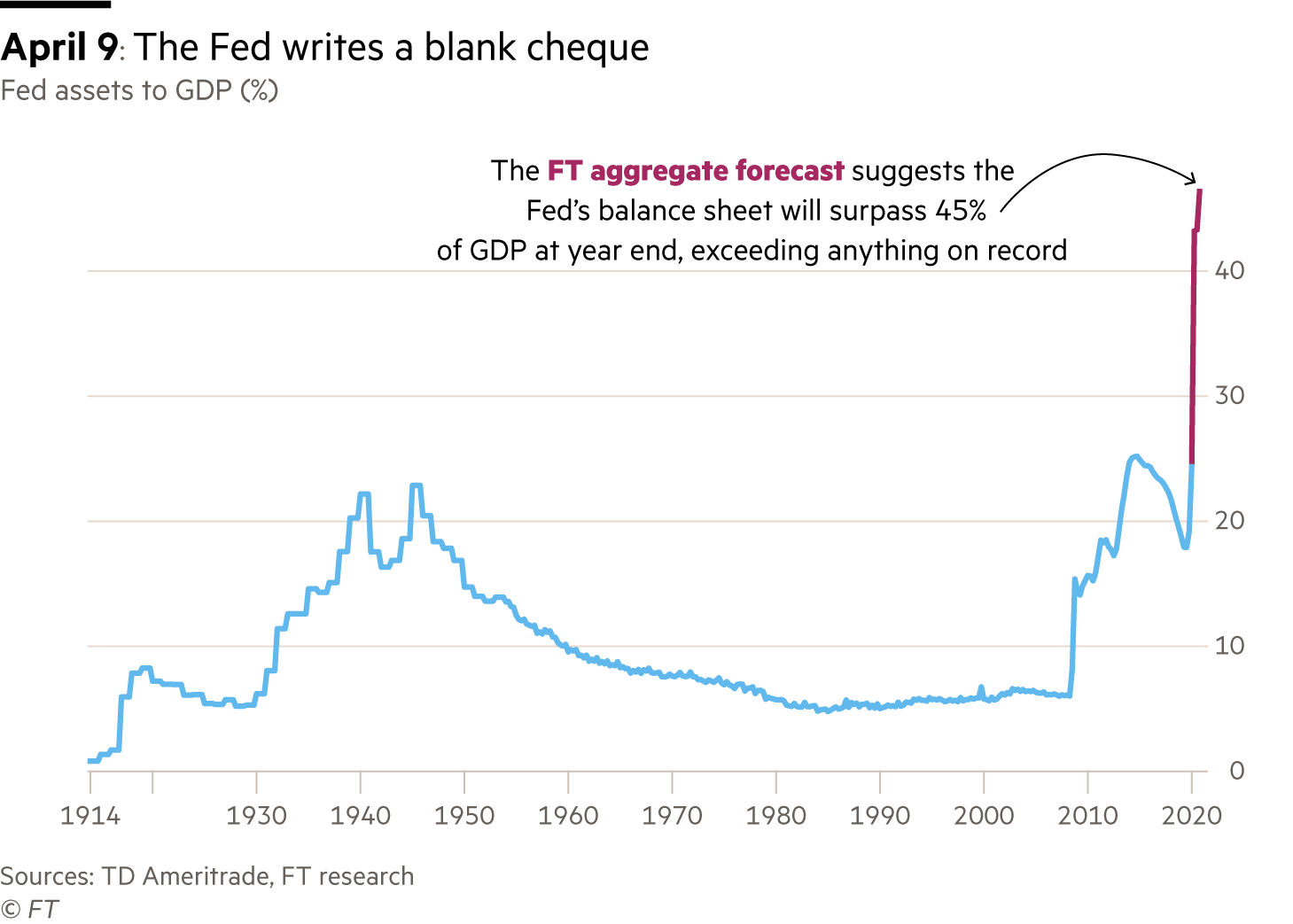

April 9 stuns investors. The Fed pledges $2.3tn in 11 emergency facilities to fund lending to a variety of markets, from municipal debt to small businesses.

We've heard from the Fed that they have their checkbook out, and it's a blank check,” says Randy Frederick, vice-president of trading and derivatives at Charles Schwab.

This new commitment is a forceful message that the central bank intends to use its power in creative ways. The old adage holds: Don't fight the Fed.

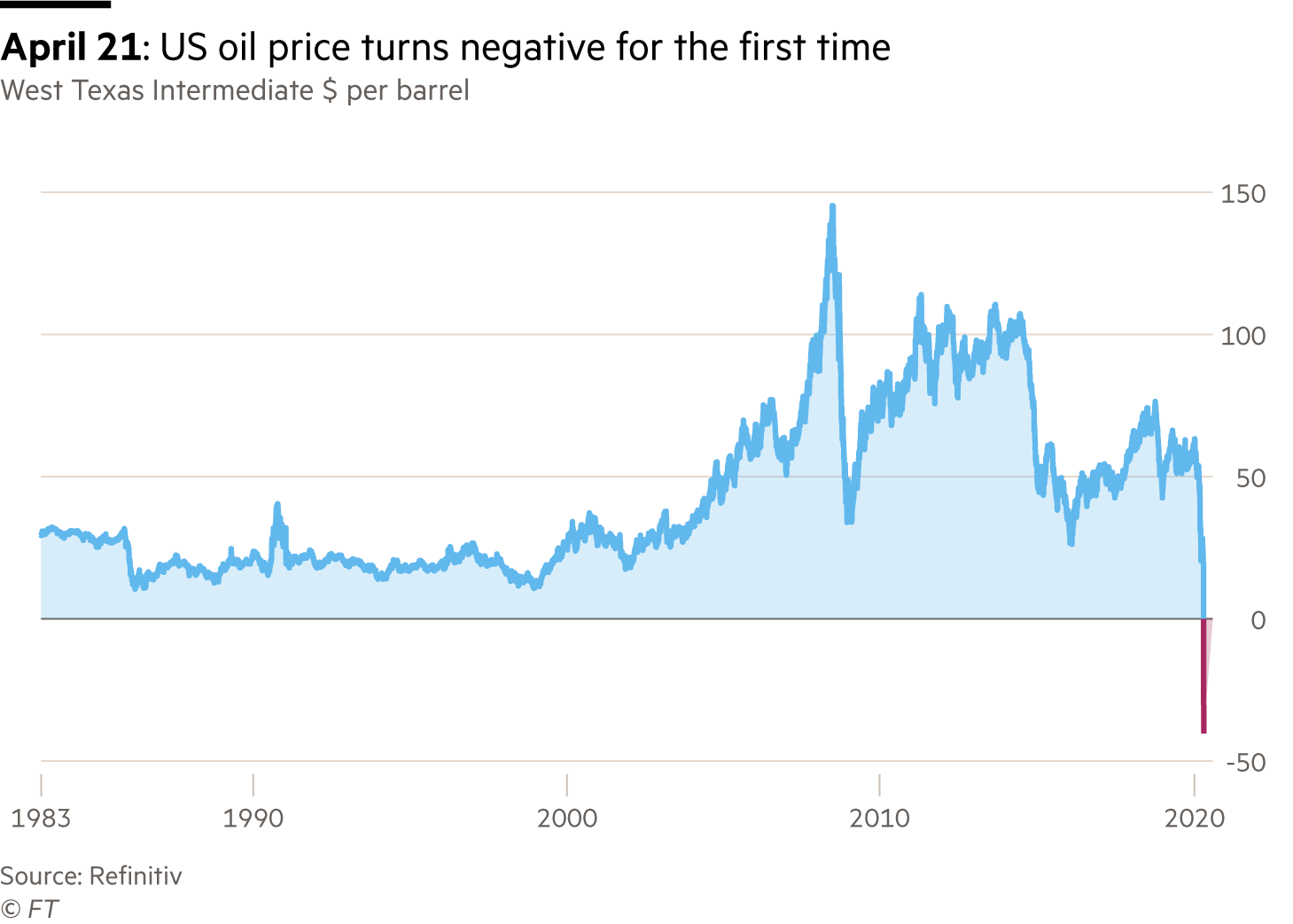

But just as markets start to get back to normal, the oil market does something stunning.

Saudi Arabia and Russia had ended their price war, but it’s too late. With economic activity at a standstill no-one has a need for all that oil sloshing around. Oil companies are trying to stash fuel away in caves, ships and disused trains.

The benchmark US price of oil plunges below zero for the first time. This means producers are paying for people to take the commodity off their hands. It tumbles to minus $40 in a record-breaking drop.

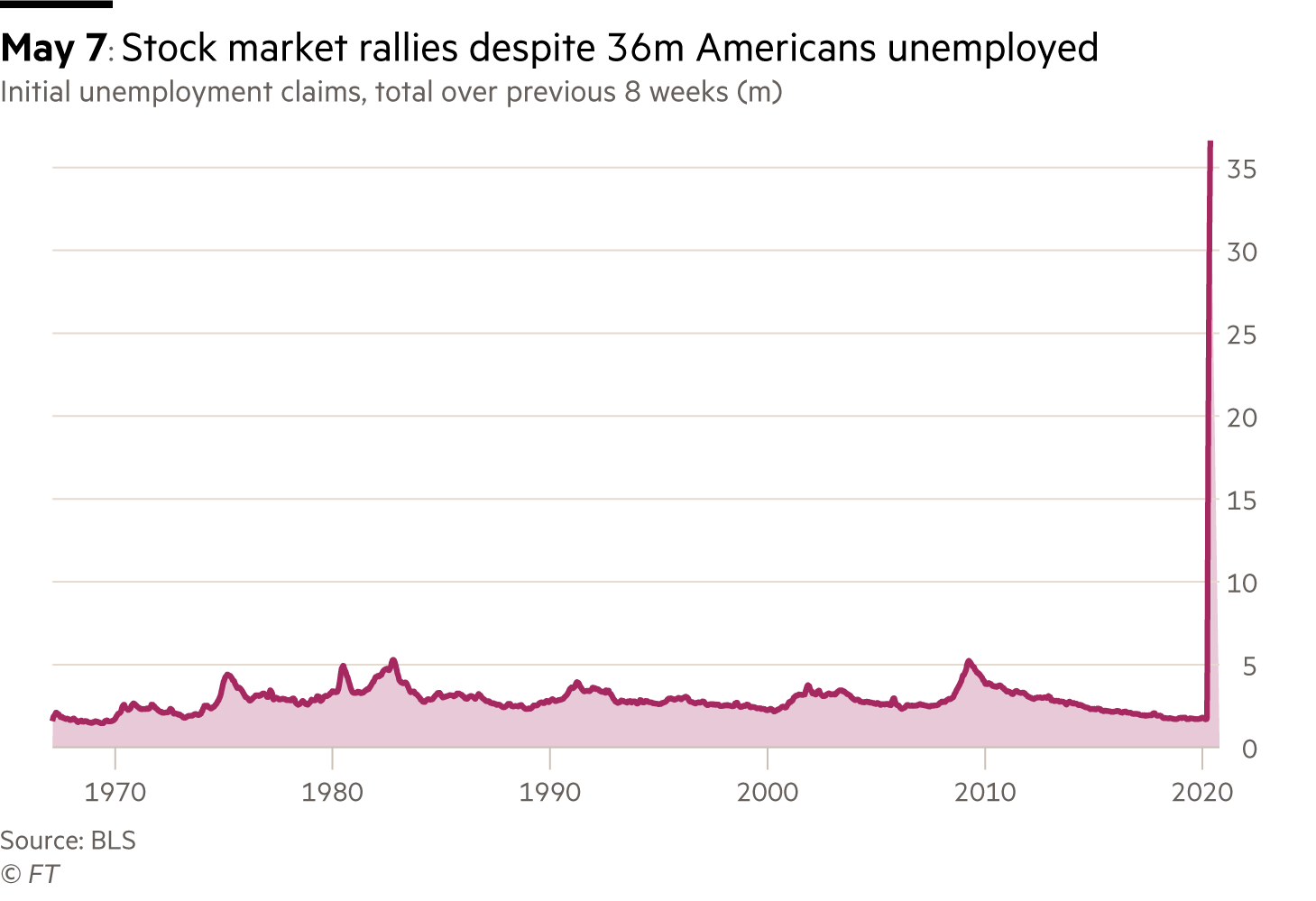

And yet stocks, particularly in Big Tech, continue to push higher. By May 7 stocks such as Apple and Amazon have risen dramatically. The Nasdaq hits a new high for the year. A world working, playing and shopping from home is all good news for the tech giants, even while sectors such as banks and energy are suffering greatly.

A month later, the S&P 500 accomplishes the same feat as the Nasdaq. Despite economic meltdown, you have regained almost all of the value you lost in February and March and you are nearly back to an even $100.

Welcome to the Terminator Rally. It simply cannot be killed no matter how bad the corporate earnings, the economy or the virus. By the end of June, US stocks have put in their best single quarter since 1998.

In early July, Chinese stocks strike their highest point in five years.

And at the end of that month, the Nasdaq makes a new record high.

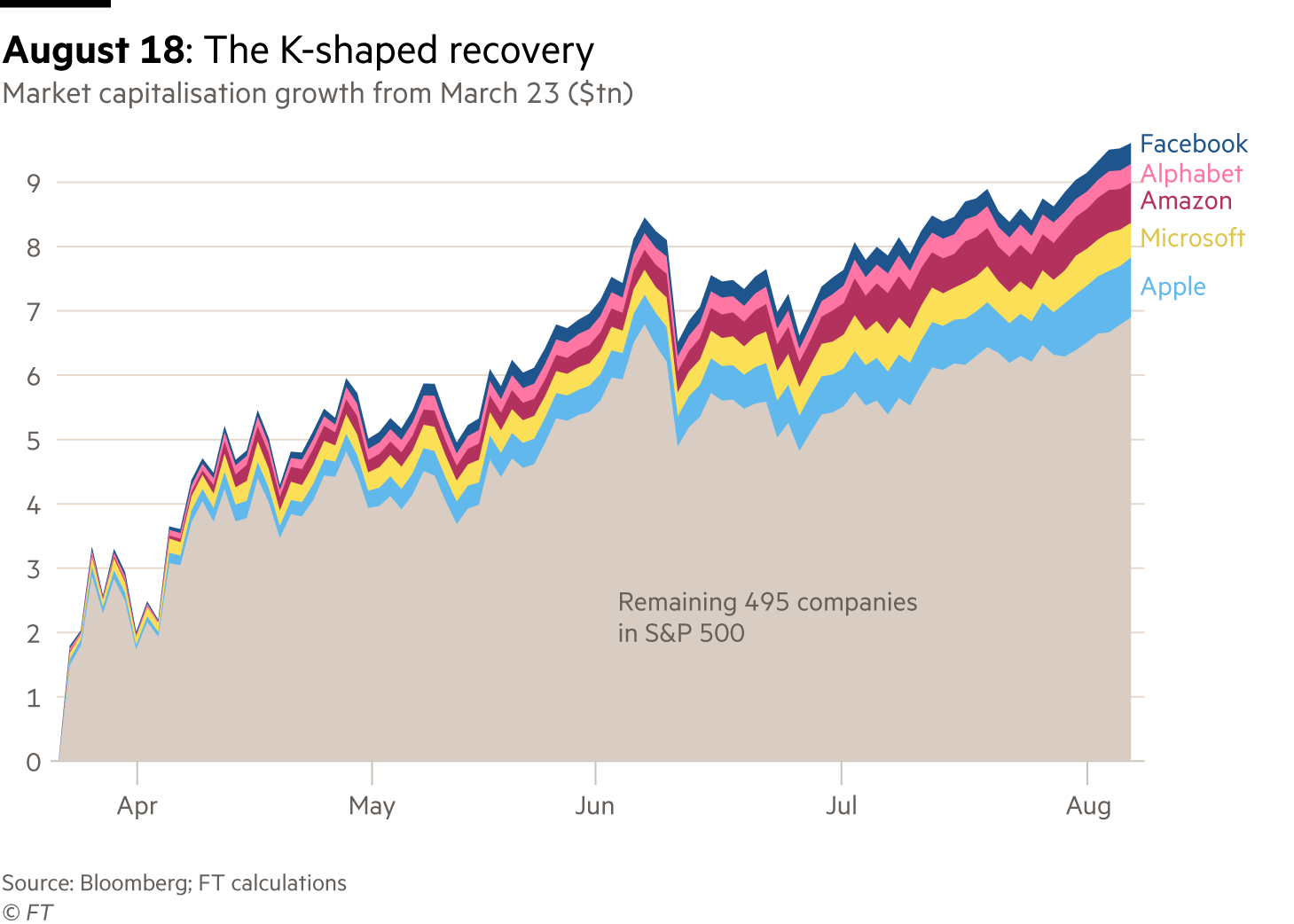

By mid-August, a huge rally in tech stocks has made the five largest companies account for a quarter of the total value of the S&P 500.

This results in a “K” shaped recovery, with a handful of companies soaring while the rest are left behind. The gap between wilting economies and runaway stock markets has never been more striking.

“This is really about a handful of stocks — not at all representing what is going on underneath the surface,” says Michael Kantrowitz, an analyst at Cornerstone.

From time to time, the cracks show. When Tesla is passed over for inclusion in the S&P 500, the carmaker's shares decline 21 per cent and the Nasdaq briefly corrects lower.

“Equities were priced to perfection,” says Alexis Gray, investment strategist at Vanguard. “That was always going to be difficult to sustain when you have a disconnect between how markets are performing and what global economies are doing.”

The next big moment for investors comes on November 9 with the announcement of a vaccine more than 90 per cent effective against Covid-19.

Stocks in beaten-up sectors such as travel start their fightback, while some of the tech whizzkids of the stock market, such as Zoom, take a knock. For the first time since March, Big Tech is not the only game in town.

Congratulations! As the year draws to a close, your $100 is now worth $114.26. Despite the rollercoaster, your annual gains are around the average over the past decade. Then again, if you'd put it instead in the Nasdaq, you’d be sitting on a nearly $40 gain.

What have we learnt? First: don’t fight the Fed. Buy whatever it buys, follow its signals. This was a huge year for central bank credibility, and they — the Fed and others — passed. How and when all this support is withdrawn is a troubling issue, but one for another day.

Second, don't fight science. One thing investors were not counting on was human ingenuity. In retrospect, they should have had more faith in a rapid vaccine.

Third, listen. The WHO did not get everything right. But warnings about the severity of coronavirus were there right at the start of the year. Investors had spent too long looking for financial crises rooted in finance and not long enough looking for economic shocks caused by things they could not control.