Lessons in Britishness

Why the rarefied world of UK boarding schools appeals to parents around the world

By Emma Jacobs

Perplexed and afraid. That is how 17-year-old Subomi Ajibola felt when she saw a hunt for the first time last year. In her home city of Lagos, dogs are commonly kept for security, so she was aghast when packs of yapping foxhounds descended on the Italianate gardens of her boarding school in Gloucestershire in the west of England. “It was quite shocking. I don’t do well with dogs — I’m not really an animal person,” she reflects. The memory makes the Nigerian teenager — who speaks with precision and projects a steely, calm air — animated and agitated.

This year, the head girl of Westonbirt School resolved to enjoy this quintessentially English pastime, so she attended a lecture on the history of the Duke of Beaufort’s trail-hunt and met the riders. “That’s an experience I can speak about in the future if I meet anyone English elsewhere. Having been to an English boarding school, it’s really nice to say you have seen it.”

Such shared upper-crust experiences are part of the reason Subomi's father, a lawyer who also attended an English boarding school, sends his daughter to Westonbirt. He is far from alone. About 20 per cent of Westonbirt’s intake is from overseas. Pupils come from 17 different countries, with the largest cohorts coming from mainland China, Nigeria and Germany. The school lays on transport to and from airports.

There is nothing new about sending children overseas to such schools. In the days of the British empire, boarding schools thrived as colonial administrators and local rulers sought to imbue their children with British culture and character. They are a staple of fiction, from Enid Blyton’s Malory Towers to Ronald Searle’s St Trinian’s and, more recently, Hogwarts, the school for wizards in JK Rowling’s Harry Potter series. Boarding schools’ image as purveyors of a gold standard of education has enticed wealthy foreign families in the 21st century to dispatch their children to the likes of Roedean, Wellington and Eton.

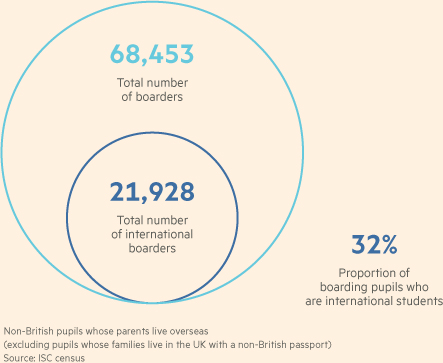

Today, 32 per cent of the UK’s boarding school pupils are non-British nationals with parents living overseas, according to the Independent Schools Council, the representative body for the UK’s independent education sector. Of the total number of non-British pupils at all the UK’s fee-paying schools — both day and boarding — with parents living overseas, the greatest number is from Hong Kong (4,704). However, among the steepest rises in recent years have been the numbers of pupils from mainland China and Russia. In 2007, 2,345 Chinese children attended UK boarding schools; last year the figure had almost doubled to 4,381. Over the same period, the number of Russian pupils more than trebled, from 816 to 2,536.

Story continues after advertisement

New worlds

As emerging markets have matured, British boarding schools have gone from being the preserve of the wealthy elite in those countries to being an object of aspiration for the middle classes, too. Families are also starting to send their children away at a younger age. According to Susan Hamlyn, director of the Good Schools Guide’s advice service, more parents from Russia and China are placing their children in British preparatory schools from the age of eight, rather than straight into senior schools at 13.

“There is massive interest in all top independent schools. We could fill the school several times over with international students,” says Anthony Seldon, master of Wellington College, a leading boarding school in Berkshire, southeast England. Such enthusiasm has even prompted some of the best-known schools, including Harrow, Sherborne and Wellington, to set up satellite schools in locations such as Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Hong Kong, Bangkok and Qatar.

‘Chinese kids work very hard and are focused on academics. The UK system can find an area for them to flourish in and build their confidence’

Education is a status symbol, but while sending a son to Eton might provide a chance to brag at a Beijing dinner party, it is not purely about acquiring the educational equivalent of a Gucci handbag. Parents, particularly in China and Russia, want to give their children more creative opportunities at school than they might gain from the rote learning and tough academic teaching in their own countries.

“Chinese kids work very hard and are focused on academics. The UK system can find an area for them to flourish in and build their confidence,” says Emma Vanbergen, education consulting director at BE Education, an advisory service for Chinese parents. She tells the story of one boy who was sporty but not a rote learner. “We found him a school that encouraged his sportiness,” she says. “It helped boost his confidence and he did better in other subjects.”

Irina Shumovitch, originally from Leningrad (she left the Soviet Union before the city was renamed St Petersburg), is an educational consultant to Russian families. She operates from her house in London — home to a hodge-podge of contemporary artwork and trinkets. Formerly a Russian teacher at St Paul’s Girls’ School in west London, she describes the educational system of her homeland as “very rigid”. “The children are not encouraged to experiment, to think for themselves, to analyse,” she says. “They’re always afraid to make a mistake. They’re not encouraged to fail. And, of course, if you don’t make a mistake and if you don’t fail you can’t move on — you can’t develop anything.”

Ms Shumovitch thinks Russian parents love the idea that their children are not “humiliated and shouted at… [they] are taken as individuals, and their abilities are noticed and developed”.

The headmistress of Westonbirt, Natasha Dangerfield, notes similarities in the Chinese system with Ms Shumovitch’s description of Russian education. “That ability to develop an all-round person is something the Chinese don’t do in the way that they educate. It is very formulaic. It is about grades and it is about performance, but it is not very much about individual development.”

Yet parents also have a desire for their children to immerse themselves in British culture and speak the lingua franca of business in preparation for the global workplace. Simon Tso, a parent from Hong Kong, sent his daughter Stephanie to Charterhouse, a boarding school in Surrey, southeast England. He hoped she would widen her horizons, familiarise herself with the west’s culture and history and develop her English. Despite his fears that she would find it hard to settle and suffer homesickness, he detects that she has gained “confidence and is more determined” in her studies.

‘Children in boarding schools win out in graduate labour market. They are self-confident, resilient and networked’

William Richardson, general secretary of the HMC (the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference), says British boarding schools are very good at making children resilient adults who can earn a good living. “Children in boarding schools win out in the graduate labour market. They do well all round, and are self-confident, resilient and networked,” he says.

Story continues after advertisement

Fees and fears

There is no shortage of overseas families that want to send their children to UK boarding schools, but the schools themselves are keen to exploit this market, the reason being, in short, the money.

Sitting in her wood-panelled office, Natasha Dangerfield is candid about the boarding school’s dependence on foreign students. Running a school is not purely about the education — it is also about the finances. About 80 per cent of her time is spent overseeing the business and 20 per cent is devoted to the curriculum.

She regularly tours Russia and China, marketing the school to interested families. The school, she says, has been “reliant on the international market”, although she is working hard on other revenue streams — for example, renting out the 210 acres of land and the former stately home that is the main school building for weddings.

International pupils hold appeal for schools such as Westonbirt because, in large part, private education has become unaffordable for many British families, Ms Dangerfield says. Fees have risen steeply in recent years: the cost of sending a child to a UK boarding school has increased 38 per cent since 2007. As the global markets went into meltdown after 2007, the average cost of a term’s tuition and boarding was £6,949; last year it was £9,596.

As the Good Schools Guide’s Susan Hamlyn observes: “Sending two or three kids to a boarding school is expensive.” Patricia Stevenson, Westonbirt’s director of admissions, who has worked at various schools over the past 17 years, has seen great changes. “Long gone are the days of following in parents’ footsteps. [Those] families who traditionally made up the lion’s share of independent school pupils now find the cost of such an education beyond their reach,” she says.

Last year, Andrew Halls, headmaster of King’s College School in Wimbledon, south London, made the headlines when he drew parallels between the banks’ excess before the financial crisis and current private school fees. He warned of an impending fee crisis, because private schools were charging too much. “We have allowed the apparently endless queue of wealthy families from across the world knocking at our doors to blind us to a simple truth: we charge too much,” he wrote in a blog.

‘The traditional English boarding family no longer sends their children to boarding school. Society has changed’

“First the nurses stopped sending children to us, then the policemen, then armed forces officers, then even the local accountants and lawyers... The most prestigious schools in the world teach the children of the very wealthiest families in the world.”

As Robin Fletcher, national director of the Boarding Schools’ Association, points out, in the context of private education, the “squeezed middle”, is not those on average incomes, but those who earn about £100,000 a year, and complain that they cannot afford boarding schools.

Yet it is not only the cost that is deterring British families — attitudes have also shifted. “The traditional English boarding family no longer sends their children to boarding school. Society has changed. They like to see their children at home,” says Ms Hamlyn.

Ms Dangerfield agrees: “Parents have a different approach to boarding. They don’t ship their child off in the UK any more like they once did.”

Many ex-boarders have spoken out in adulthood about their traumatic experiences at school. Prince Charles, who attended Gordonstoun in Scotland, described his time there in the 1960s as a prison sentence: “Colditz in kilts.”

Therapists have criticised the practice of sending children away from their families. Joy Schaverien, a psychotherapist, proposed the classification of a cluster of symptoms and behaviours as “Boarding School Syndrome”. In a 2011 paper in the British Journal of Psychotherapy she wrote: “Children sent away to school at an early age suffer the sudden and often irrevocable loss of their primary attachments; for many this constitutes a significant trauma… In order to adapt to the system, a defensive and protective encapsulation of the self may be acquired; the true identity of the person then remains hidden. This pattern distorts intimate relationships and may continue into adult life.”

A support group, Boarding School Survivors, was founded in 1990 to help adults affected by boarding. Stories of sexual abuse by teachers in decades gone by have done much to undermine parents’ confidence in the system.

Boarding schools counter that much has changed since Prince Charles’s time. Pastoral care is a priority today and technology makes families just a Skype call away. William Richardson, HMC general secretary, says boarding schools have modernised and many offer a mix of boarding and day schooling — attractive to families in which both parents work.

“The boarding sector is quite confident — proponents of boarding believe they have strong story to tell of pastoral care,” says Mr Richardson. In a fast-changing world fraught with parental anxiety about children’s safety, particularly online, such an education is an attractive proposition.

Foreign pupils not only offer British boarding schools the prospect of revenue but academic gain too. For schools dependent on league tables as marketing tools, Russian and Chinese children, who have been drilled in exams, can be a tempting way to bolster performance.

Culture shock

With so many foreign pupils come problems. On a personal level, a child far removed from family is vulnerable to homesickness. While English boarders may be able to escape school for the night, weekend or half-term at home, such excursions are not viable for a pupil from Beijing.

There is also the culture shock. Subomi at Westonbirt says she found the isolation of her boarding school difficult. When she arrived at Westonbirt, she went a whole week unable to speak to her family because she did not know how to get a Skype connection.

Technology can shrink the distance from home. Mobile phones, Skype and WhatsApp may lessen the pangs but can sometimes exacerbate them. A teary email from a child after flunking a maths exam might escalate in a way that it would not if the parent could talk to the child at the kitchen table.

The demands of the English education system can require a big adjustment, too. Subomi says she has occasionally found adapting difficult. “The way we learnt [in Nigeria] is, you learn it, not particularly understand or apply it. You’re not asked to explain or evaluate. I struggled when I had to give my own opinion. [In Nigeria], black is black and white is white. But here you have to explain why black is black.”

She still has problems with the food, though. Two of her friends are drawn into the conversation about school lunches. Sixteen-year-old Lucrezia Antinori from Rome says that when she first spied the cream on puddings she thought it was “gross”, but now she is rather partial to it. Chloe Au, 18, from Hong Kong, longs for Sunday roasts. “I love Yorkshire pudding,” she says.

Rogue agents and advisers preying on parental anxiety can also be problematic. Some agents are paid on a commission basis, placing their charges in unsuitable schools simply to earn the cash. Another trick is to persuade parents to keep moving children to different schools. With each move, the agent charges another commission — a process Ms Dangerfield describes as “handbag shopping”.

Ms Hamlyn says many agents are “completely unscrupulous [and] have never even been to the UK”, so are in no position to recommend schools. She remembers one call from a Chinese mother who said she had heard Harrow was the best school and wanted to send her daughters there. No one had told her the school was exclusively for boys.

Guardians provide a home away from school at weekends and half-terms and if a medical emergency arises. Many are nurturing hosts but, as with rogue agents, others are just in it for the money. Stories are rife of ruthless guardians packing children into rooms with numerous bunkbeds. Ms Dangerfield came across one who only let his charges use the bathroom for seven minutes in the morning and made no effort to include them in home life. Consequently the girls did not leave their room for a whole weekend.

Ghettoised communities within schools are another problem. Integration can prove difficult. Many boarding schools have been criticised by parents and in the UK press for accepting too many children from one nationality, with the result that those children make little effort to speak English or adapt to school life.

When Ms Dangerfield arrived at Westonbirt two years ago, she felt there were too many Chinese girls. “It meant they were able to be one group and not integrate with the rest of their school, which made the reason for them coming here completely redundant.” She set about reducing the intake and trying to integrate various nationalities. Girls are permitted to speak in their mother tongue only in the evenings or at weekends, for example.

Subomi believes the balance today is right. “Sometimes I wish there were more Nigerian girls. But if there were, I wouldn’t [have] the full English boarding school experience,” she says.

Ostentatious wealth can also be difficult. There are a few girls who have “an awful lot of money”, says Ms Dangerfield. They go to London “and come back with bags full of Louis Vuitton and ridiculous amounts of money spent — and not a lot of work going on”.

The future is now

A school and all its pupils benefit from a diverse and international intake, says Wellington College’s Anthony Seldon. “They give an unbelievable amount to the school culture,” he says. “Our young people are going to be working abroad and it gives them a good foundation. If you can get to know foreign pupils as individuals, you use the perfume they bring to enrich the school.”

Robin Fletcher of the Boarding Schools’ Association says many schools want the cultural mix that international students bring. “Having only one type of child is not good for a school,” he says.

Westonbirt’s A-level history group — just four girls — are studying pre-revolutionary Russia. Their teacher observes that the presence of a girl from Moscow has enlivened discussions. The Russian girl picks up on what she perceives to be the anti-Russian nature of some textbooks.

English education can improve Russian life generally, Irina Shumovitch believes. She tells the story of one oligarch’s child who puts his Vertu designer phone away when he goes to school in favour of an old Nokia, because he is wary of being ostentatious.

What is the outlook for British boarding schools? The proportion of international pupils dipped slightly in 2014 — to 32 per cent from 34 per cent the previous year. Mr Fletcher believes the strengthening UK economy might boost the number of British boarders in the coming years. “I am sensing a degree of confidence from schools,” he says.

There is, however, concern among schools that the poor state of the eurozone economy, as well as political instability and the plunging rouble in Russia, might stem the flow of foreign pupils. Ms Shumovitch, though, thinks the situation in Russia might mean more affluent people will take their children — and their money — out of the country.

Whatever the proportions of various nationalities, foreign pupils will remain a fixture in British boarding schools — a prospect that pleases Subomi, who sees her time Westonbirt as “a wonderful experience”.

But to get the best out of British education means being open to new ideas, she says. “If you are coming here with a closed mind, you stick to what you know and are not open to different things, it might not work as well for you.” She recommends pupils be prepared to “see odd things or experience life in a different way”.

Ms Dangerfield insists that despite the cultural differences, teenagers are the same the world over. “A teenage girl from Russia is the same really as a teenage girl from the UK. You will still have discussions about the length of your school skirt. You will still have discussions about how disgusting lunches are. And [pop groups, such as] One Direction transcend everything.”

International pupils' keepsakes and mementos from home

Story continues after advertisement

Credits:

Written by Emma Jacobs

Video filmed and edited by Charlie Bibby

Photography by Charlie Bibby

Design by Kari-Ruth Pedersen and Caroline Nevitt

Edited by Helen Barrett

Graphics by Chris Campbell

Statistics by Gavin Jackson. Source (unless otherwise stated): The Good Schools Guide

Production by George Kyriakos, Andy Mears and Phillip Parrish

Additional photography by Alamy, Dreamstime, Tim Graham/Robert Harding/Rex

Read the rest of the series

Let me know when the next part of the Distinctive Living series is published