Waking to a nightmare

The nightmare for Yoshiaki Kawata would start at midnight with a huge earthquake under the waters of Suruga Bay. Most people in the coastal cities of Fuji, Shizuoka and Hamamatsu in Japan’s Tokai region would be at home asleep as their homes begin to shake from tremors far stronger than those that struck the Tohoku region in 2011. Five minutes later, a 10m tsunami arrives.

“People in houses will be hurt by [the] shaking and then a tsunami coming,” says Mr Kawata, an earthquake expert and professor of safety science at Kansai University. Hundreds of thousands of people could die.

This is not an alarmist message from a university professor but the Japanese government’s official worst case scenario for a disaster it considers highly likely to occur within the next 30 years: an earthquake of between 8.0 and 9.0 magnitude in the tectonic plate boundary called the Nankai Trough. While the worst case is not the probable one, the government publicised the scenario in 2013, with Shinzo Abe, prime minister, calling on the Japanese people to be “calmly and appropriately afraid”.

The recent magnitude 7.3 earthquake on the southern island of Kyushu, which killed at least 49 people and destroyed thousands of homes, is a reminder that Japan remains exposed to frequent natural disasters. But a big earthquake in the Nankai Trough, or directly below Tokyo, would be an economic shock of global significance. It would cost as much as 40 per cent of Japan’s gross domestic product and disrupt worldwide supply chains at companies such as Toyota, with repercussions for everything from the yen to national defence and the country’s public debt.

“If we have a disaster on this scale now, the country will go under,” says Kimiro Meguro, professor of earthquake mitigation engineering at the University of Tokyo. “There are plenty of examples of this in world history.”

Understanding the risks and potential consequences of a disaster, such as a Nankai Trough earthquake, is therefore crucial to understanding Japan’s future — and preparing for it.

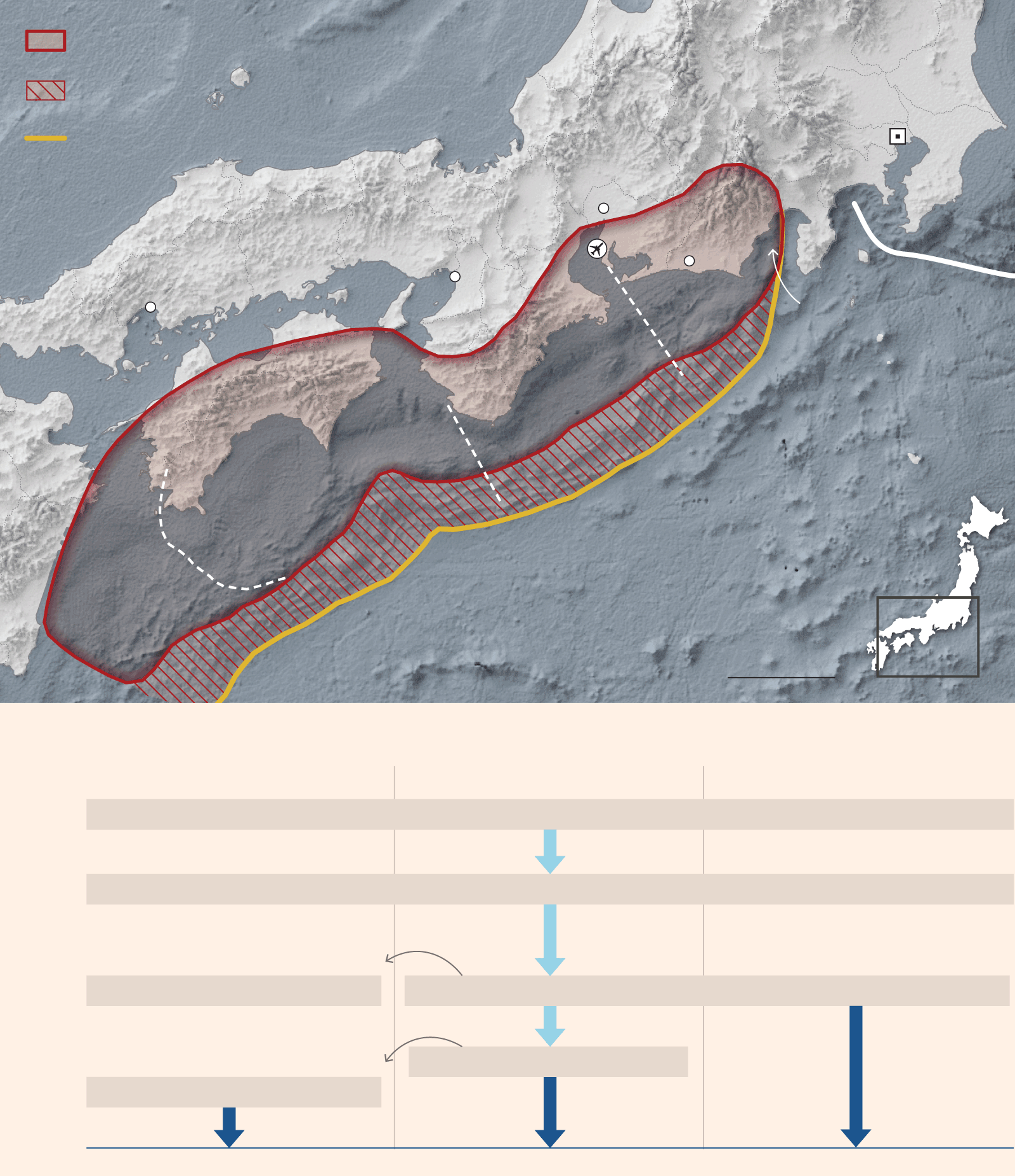

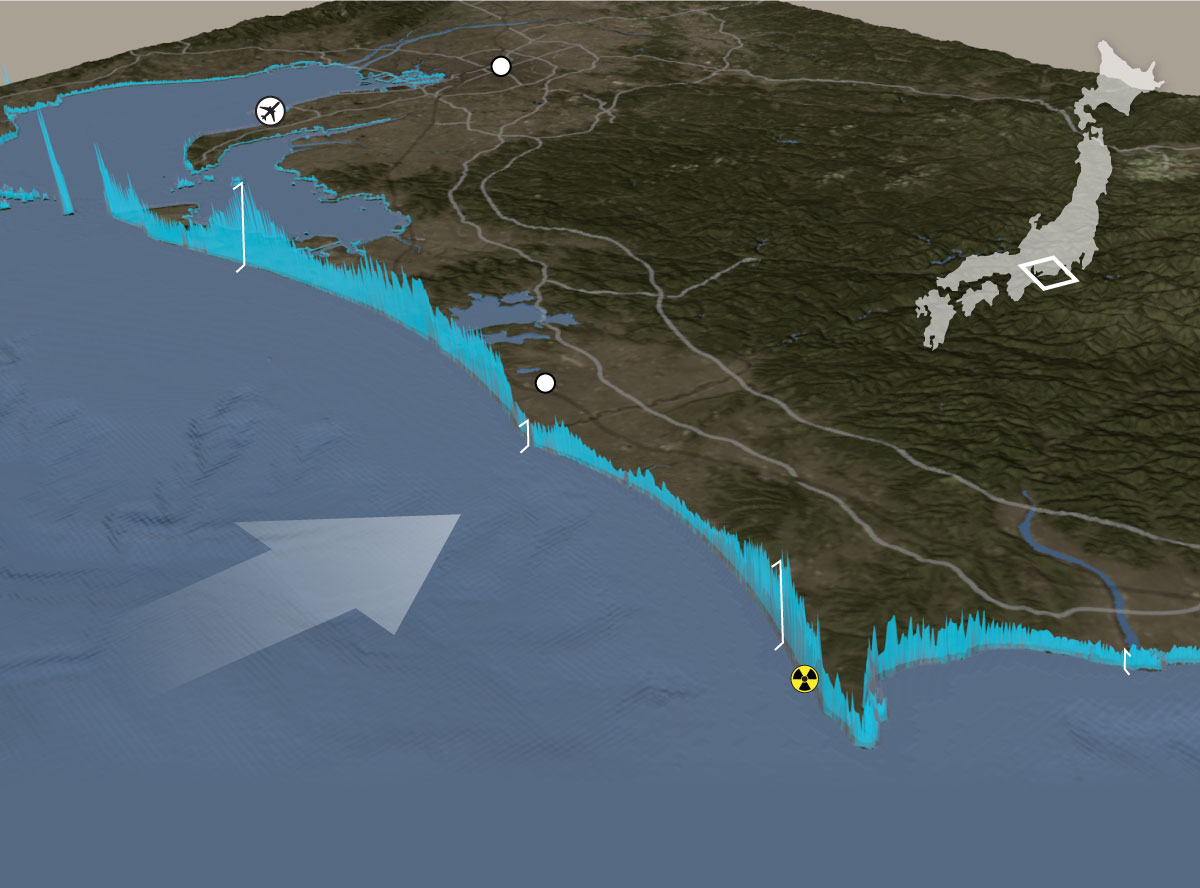

A precarious trough

The country’s precarious seismology is simple to understand. It sits at the boundary of four tectonic plates, shot through with faults like crazy paving. Those plate boundaries give rise to “megathrust” earthquakes in the seas off Japan’s Pacific coast such as the magnitude 9.0 Tohoku earthquake in March 2011. In the western part of Japan, the plate boundary is marked by an underwater trench called the Nankai Trough. The Sagami Trough runs further east, facing Tokyo.

A large earthquake has struck the Nankai Trough every 100 to 150 years. The trough is split into three main sections, known, from west to east, as Nankai, Tonankai and Tokai; quakes hit the two easterly sections in the mid-1940s, but the Tokai section has been quiet for 158 years.

Revised tsunami source area (2012)

Additonal source rupture and tsunami area (2012)

Tokyo

Nankai Trough

Japan

Nagoya

Honshu

Hamamatsu

Chubu

Sagami Trough

Osaka

Tokai

Hiroshima

Suruga Bay

Tonankai

Shikoku

Nankai

Kyushu

JAPAN

100km

Large earthquakes in the Nankai Trough since 1600

Nankai

Tonankai

Tokai

1605

Keikyo (mag 7.9)

102 years

Houei (mag 8.6)

1707

147 years

32 hours later

Ansei Tokai (mag 8.4)

Ansei Nankai (mag 8.4)

1854

90 years

Tonankai (mag 7.9)

1944

2 years later

Nankai (mag 8.0)

1946

162 years

70 years

72 years

2016

Tokyo

Japan

Nagoya

Honshu

Hiroshima

Tokai

Sagami

Trough

Osaka

Suruga Bay

Tonankai

Shikoku

Nankai

100km

Revised tsunami source area (2012)

Additonal source rapture and tsunami area (2012)

Nankai Trough

Large earthquakes in the Nankai Trough

since 1600

Nankai

Tonankai

Tokai

Mag 7.9

1605

102

years

Mag 8.6

1707

147

years

32 hours later

Mag 8.4

Mag 8.4

1854

90

years

1944

Mag 7.9

2 years later

1946

Mag 8.0

158

years

66

years

68

years

2016

That long and ominous silence has made a Tokai earthquake the most feared and anticipated in Japan. “The worst case is that Tokai, Tonankai and Nankai earthquakes occur simultaneously,” says Mr Kawata. “That would have a magnitude of 9.0. Independently, a Tokai earthquake could be 8.0.”

The government’s figures put the odds of a magnitude 8.0-plus Nankai Trough earthquake at 50 per cent in the next 20 years, 70 per cent in the next 30 years and 90 per cent in the next half century.

These official numbers have some critics. Robert Geller, a seismologist at the University of Tokyo, has argued that such precise forecasts are spurious, urging Japan to prepare for the unpredictable. The Kyushu earthquake, like Tohoku and the 1995 Kobe disaster, was merely the latest to occur in an area the government classed as low risk.

Whatever the precise odds, a Tokai quake is the most studied and modelled, making it a useful guide on the economic and social consequences of a large quake in a core industrial area.

Deep impact

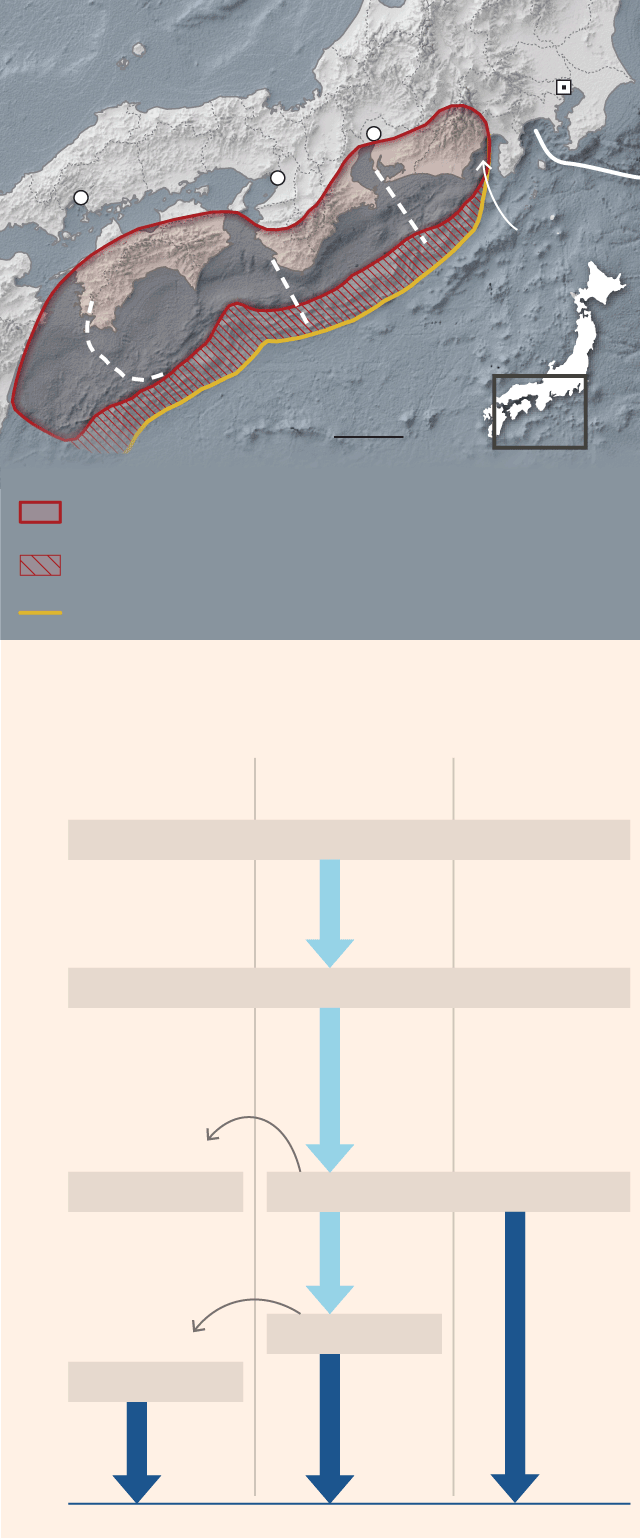

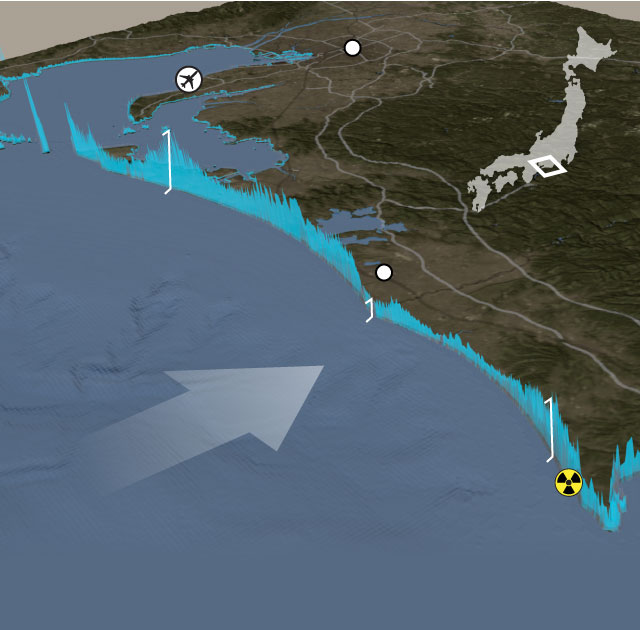

A Tokai earthquake could be more devastating than Tohoku, which left 18,800 people dead and missing, thousands homeless and crippled the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear facility. It is a densely populated area and the potential epicentre is close to shore.

The tsunami caused by the Tohuku quake took at least 25 minutes to reach land and struck during daylight when the population was awake and able to react.

“But in Shizuoka prefecture [in central Japan, about 200km west of Tokyo], a tsunami more than 10m high could strike within five minutes,” Mr Kawata says. “That makes it very difficult to evacuate.”

Chubu

airport

Nagoya

Ise Bay

JAPAN

17m

Hamamatsu

9m

Tsunami reaches land in less than five minutes in some areas

19m

6m

Hamaoka nuclear

power station

Suruga Bay

Tsunami reaches up

to 30m in height

Chubu

airport

Nagoya

JAPAN

17m

Tsunami reaches land in less than five minutes in some areas

Hamamatsu

9m

19m

Hamaoka nuclear

power station

Tsunami reaches up

to 30m in height

Chubu

airport

Nagoya

17m

JAPAN

Hamamatsu

9m

19m

6m

Hamaoka nuclear

power station

Suruga Bay

Tsunami reaches land in less than five minutes in some areas

Tsunami reaches up

to 30m in height

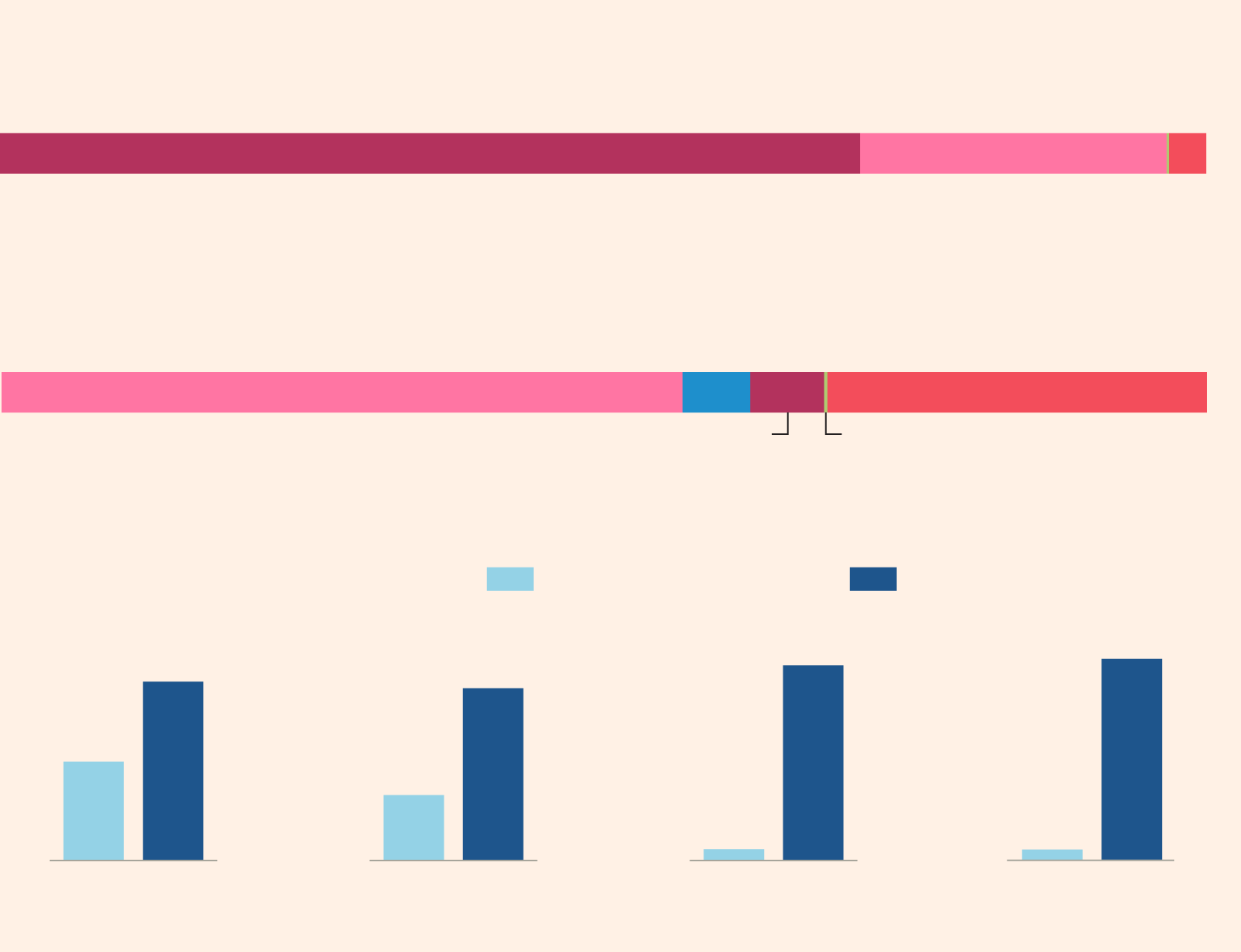

The estimates of casualties are frightening: in the worst case, the government expects 323,000 deaths. Of these 230,000 would be due to the impact of the tsunami, 82,000 from the collapse of houses and 10,000 due to fire. As many as 2.4m houses would be destroyed.

Rail and road links connecting eastern and western Japan would be cut. Most houses in the region would initially be without water and electricity. The region’s only nuclear plant is mothballed — as is every Japanese nuclear plant bar one — but a disaster on this scale could have unpredictable knock-on effects.

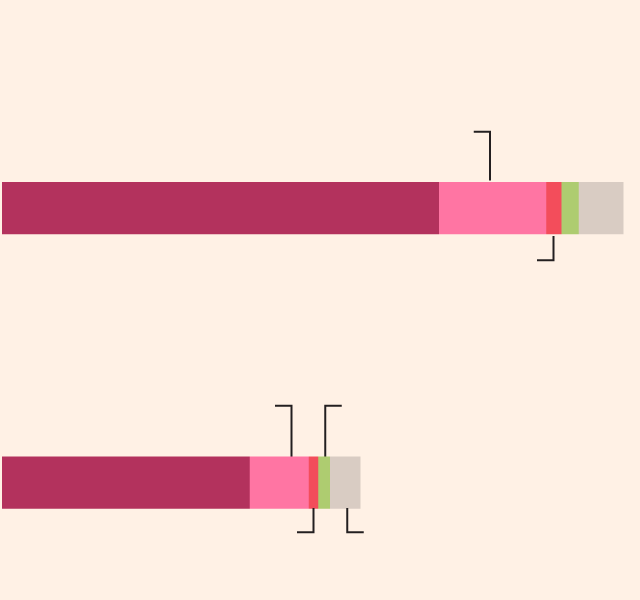

Estimated damage – worst case

Deaths

Tsunami

230,000

Tremor

82,000

Landslide

600

Total: 323,000

Fire

10,000

Buildings

Tremor

1.3m

Tsunami

146,000

Fire

750,000

Liquefaction

134,000

Landslide

6,500

Total: 2.4m

Comparison between Tohoku and worst-case Nankai earthquake

Tohoku (mag 9. 0)

Nankai (mag 9.0)

2.39m

323,000

1,015

1.63m

561

0.62m

18,800

0.13m

Wetted surface

area (km2) 1

Population of

wetted area 1

Dead and

missing 2

Building damage

(completely destroyed) 3

Estimated damage – worst case

Deaths

Total: 323,000

Tsunami

230,000

Tremor

82,000

Landslide

600

Fire

10,000

Buildings

Total: 2.4m

Tremor

1.3m

Tsunami

146,000

Fire

750,000

Liquefaction

134,000

Landslide

6,500

Comparison between Tohoku and

worst-case Nankai earthquake

Nankai (mag 9.0)

Tohoku (mag 9. 0)

Wetted surface area (km2) 1

1,015

561

Population of wetted area 1

1.63m

0.62m

Dead and missing 2

323,000

18,800

Building damage (completely destroyed) 3

2.39m

0.13m

Estimated damage – worst case

Deaths

Tsunami

230,000

Tremor

82,000

Landslide

600

Fire

10,000

Total: 323,000

Buildings

Tremor

1.3m

Tsunami

146,000

Fire

750,000

Liquefaction

134,000

Landslide

6,500

Total: 2.4m

Comparison between Tohoku and worst-case Nankai earthquake

Tohoku (mag 9. 0)

Nankai (mag 9.0)

2.39m

323,000

1,015

1.63m

561

0.62m

18,800

0.13m

Wetted surface

area (km2) 1

Population of

wetted area 1

Dead and

missing 2

Building damage

(completely destroyed) 3

1: Assumed wetted surface area when seawalls and floodgates function properly during earthquake motion

2: Damage when earthquake motion is landward, tsunami level is 1, it is midnight in winter and the wind speed is 8m/s

3: Damage when earthquake motion is landward, tsunami level is 5, it is evening in winter and the wind speed is 8m/s

Breaking the chain

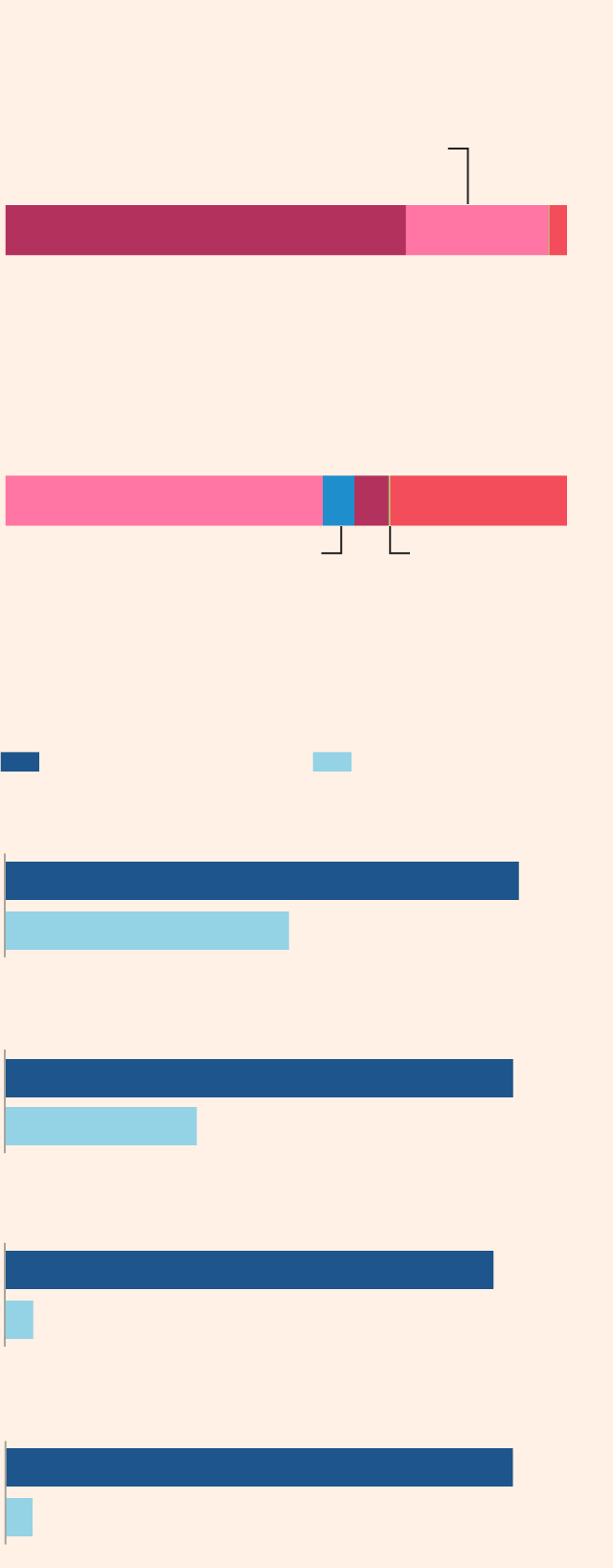

The global impact of the Tohoku earthquake surprised many. Car plants as far afield as Louisiana and Ohio had to halt production for a lack of parts, from microcontrollers to paint.

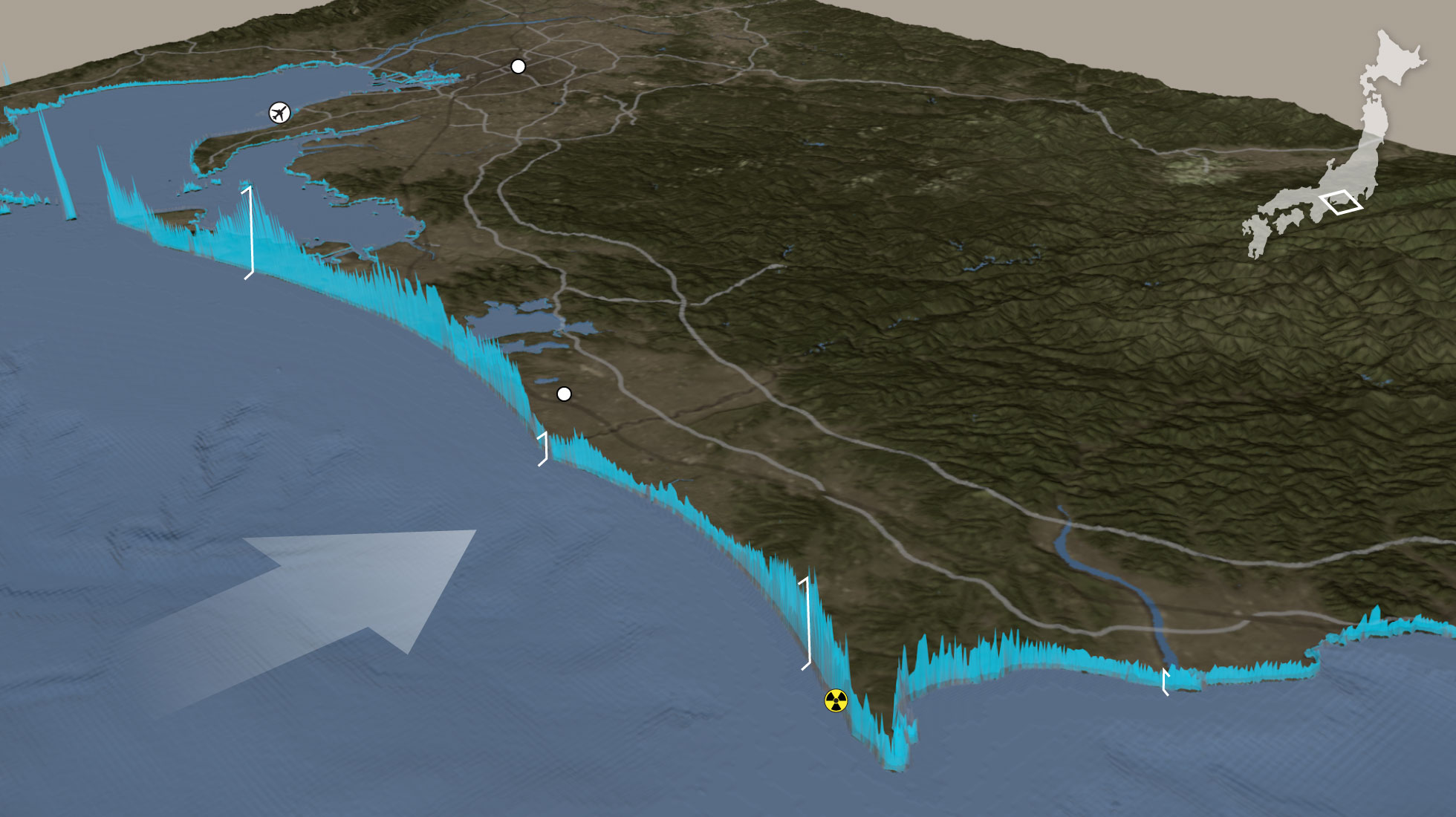

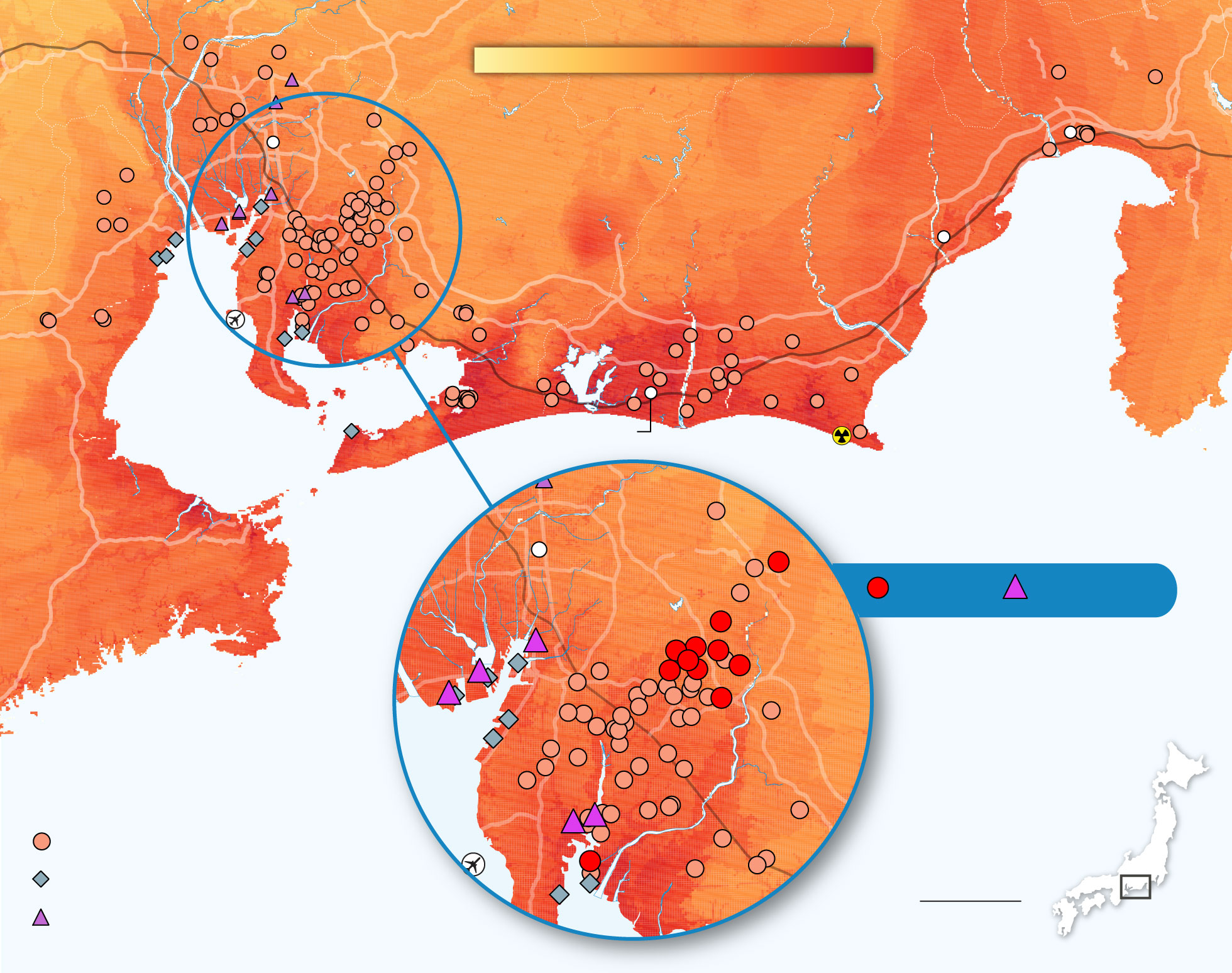

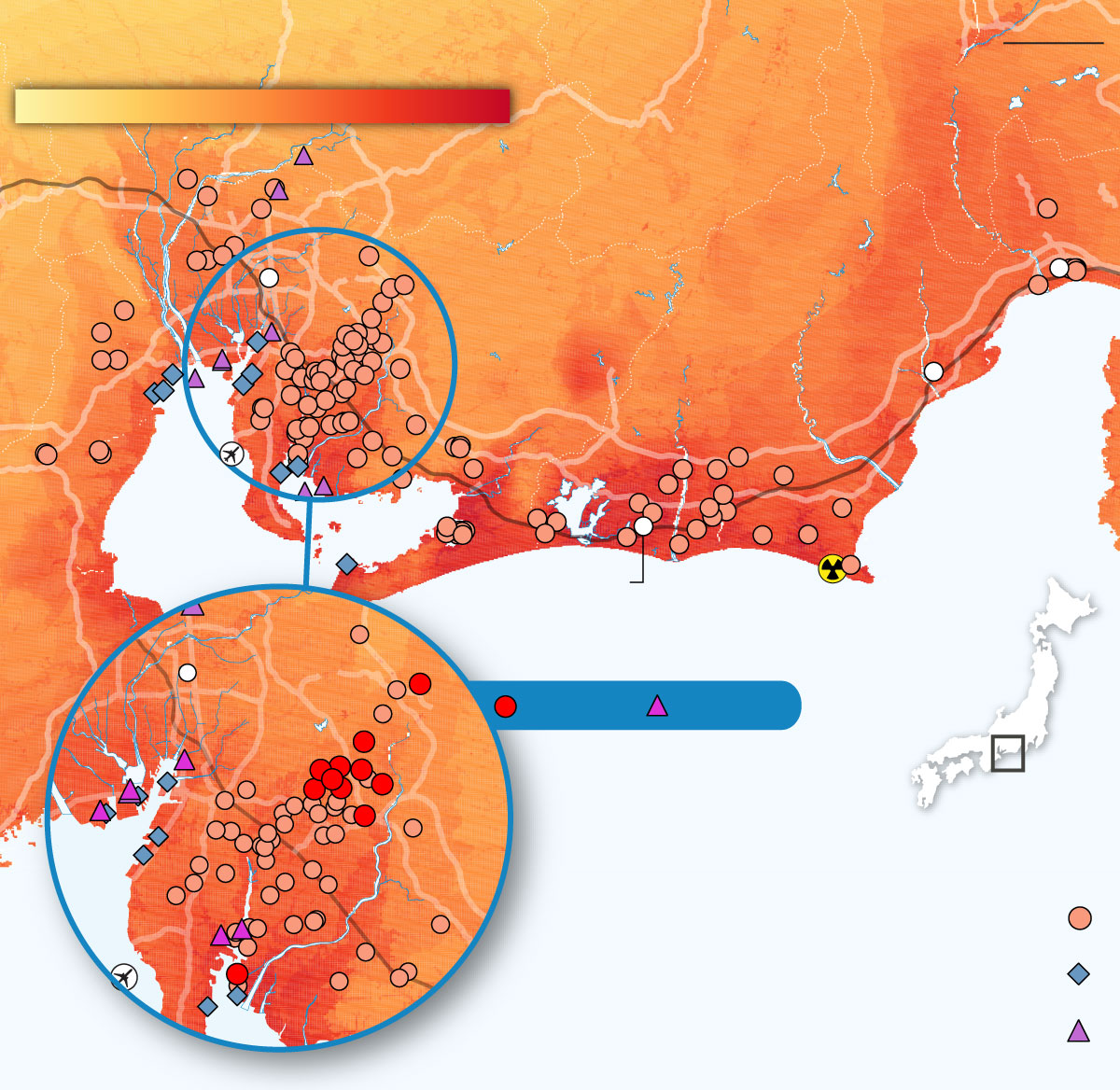

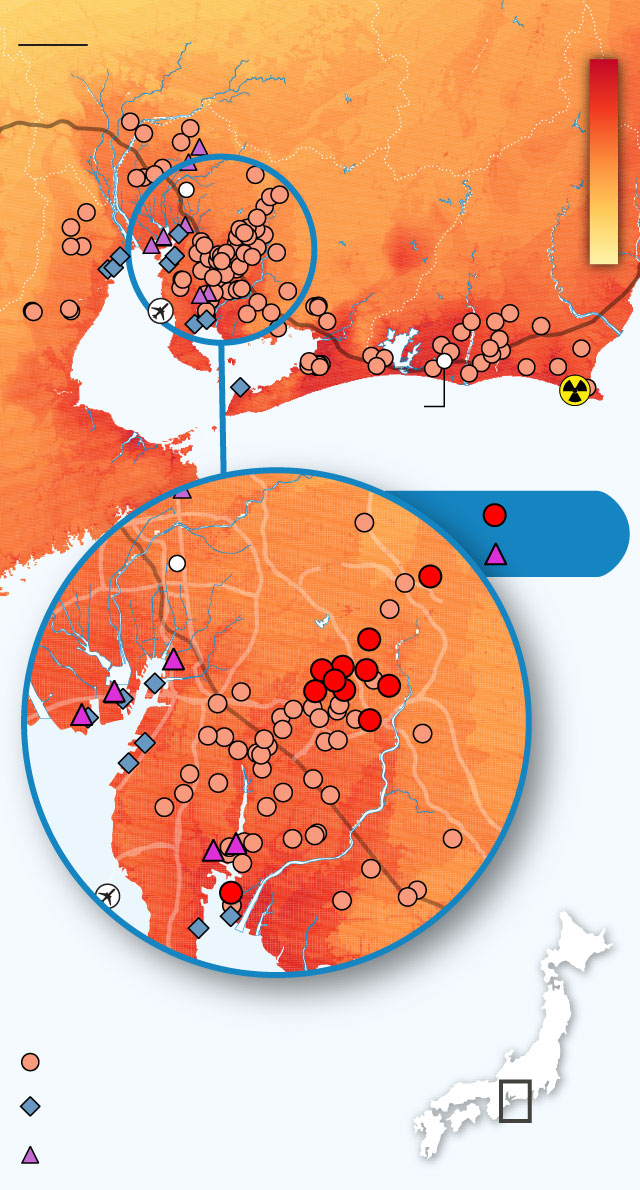

Yet Tohoku is on the periphery. Tokai is a manufacturing heartland, a link in some of the world’s most important supply chains.

Fanuc, the world’s leading maker of industrial robots, is based near Fuji. About half the world’s musical instruments, manufactured by Yamaha and Roland, come from Hamamatsu. One-third of the world’s Nand Flash memory, built into every smartphone, comes from a Toshiba factory south of Nagoya.

But even in this region, two supply chains stand out: it is home to Toyota, the world’s biggest carmaker, and to most of Boeing’s Japanese suppliers. Toyota makes about 1.6m vehicles a year in the region, similar to the entire UK car industry. Its Lexus plant on the waterfront at Tahara is often cited as the world’s leading auto factory.

4.2

7.3

Shinkansen

JMA seismic intensity scale

Fuji

Nagoya

Shizuoka

Suruga Bay

Chubu

airport

Ise Bay

Hamamatsu

Hamaoka nuclear

power station

Nagoya

Toyota

Boeing

Key structures by industry

Automotive

JAPAN

power stations

20km

Aerospace

20km

JMA seismic intensity scale

4.2

7.3

Shinkansen

Fuji

Nagoya

Shizuoka

Suruga Bay

Chubu

airport

Ise Bay

Hamamatsu

Hamaoka nuclear

power station

Nagoya

Toyota

Boeing

JAPAN

Key structures by industry

Automotive

power stations

Aerospace

JMA seismic intensity scale

20km

7.3

Shinkansen

Nagoya

4.2

Chubu

airport

Hamamatsu

Hamaoka nuclear

power station

Toyota

Nagoya

Boeing

Key structures by industry

JAPAN

Automotive

power stations

Aerospace

Effect of earthquake on reinforced-concrete buildings

| JMA seismic intensity | High resistance | Low resistance |

|---|---|---|

| 5 upper | - | Cracks may form in walls, crossbeams and pillars |

| 6 lower | Cracks may form in walls, crossbeams and pillars | Cracks are more likely to form in walls, crossbeams and pillars |

| 6 upper | Cracks are more likely to form in walls, crossbeams and pillars | Slippage and X-shaped cracks may be seen in walls, crossbeams and pillars. Pillars at ground level or on intermediate floors may disintegrate, and buildings may collapse |

| 7 | Cracks are even more likely to form in walls, crossbeams and pillars. Ground level or intermediate floors may sustain significant damage. Buildings may lean in some cases | Slippage and X-shaped cracks are more likely to be seen in walls, crossbeams and pillars. Pillars at ground level or on intermediate floors are more likely to disintegrate, and buildings are more likely to collapse |

Human reaction to earthquake

| JMA seismic intensity | Reaction |

|---|---|

| 4 | Most people are startled. Felt by the majority of people walking. Most people wake up |

| 5 lower | Many people are frightened and feel the need to hold onto something stable |

| 5 upper | Many find it hard to move; walking is difficult without holding onto something stable |

| 6 lower | It becomes difficult to remain standing |

| 6 upper / 7 | It is impossible to remain standing or move without crawling. People may be thrown through the air |

Much of the wing and fuselage of the Boeing 777 and 787 is manufactured at a cluster of plants on Nagoya Bay, belonging to Mitsubishi, Kawasaki and Fuji Heavy Industries. Mitsubishi and Kawasaki declined to comment on earthquake preparedness. Toyota offered an interview but cancelled it after the Kyushu quake, saying the responsible executive was too busy.

Japanese business learnt a lot from the Tohoku disaster. “Our big companies changed their supply chain systems to increase redundancy,” says Mr Kawata, meaning alternative sources for crucial components. The big manufacturers have extensive continuity plans.

However, even if Toyota’s own plants managed to restart quickly, it is only as resilient as its weakest subcontractor and it relies on regional infrastructure. Car exports go mainly via piers in Nagoya Bay; Boeing’s parts are flown to the US from Chubu airport, built on artificial land in the same bay. All could be exposed to the risk of tsunamis.

Mr Meguro raises another issue. “Electricity used to come from a distance, but with the shutdown of nuclear plants after Tohoku, Tokyo’s electricity comes from combustion plants around Tokyo Bay,” he says. Similarly, Nagoya’s electricity is generated locally.

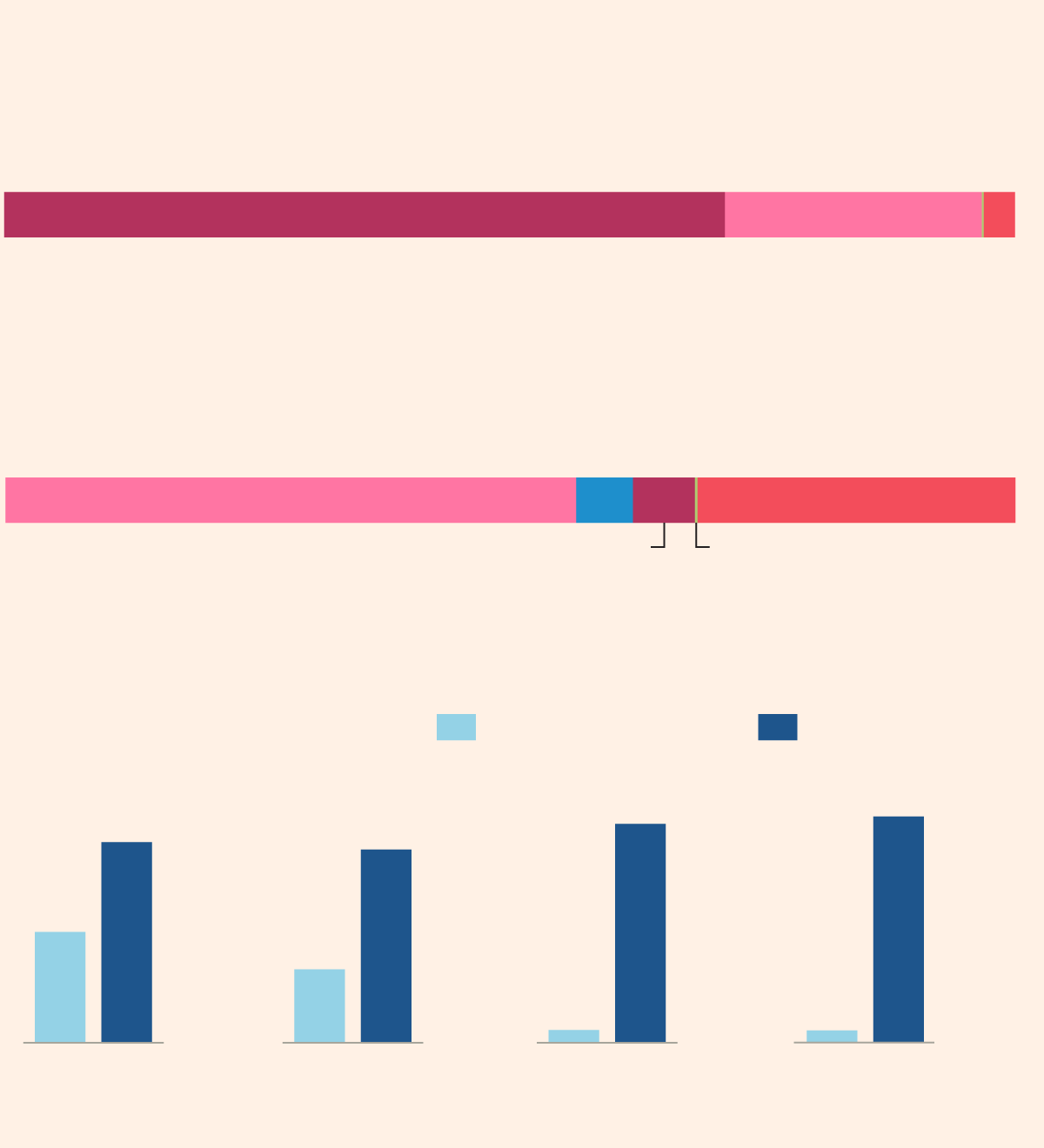

Counting the cost

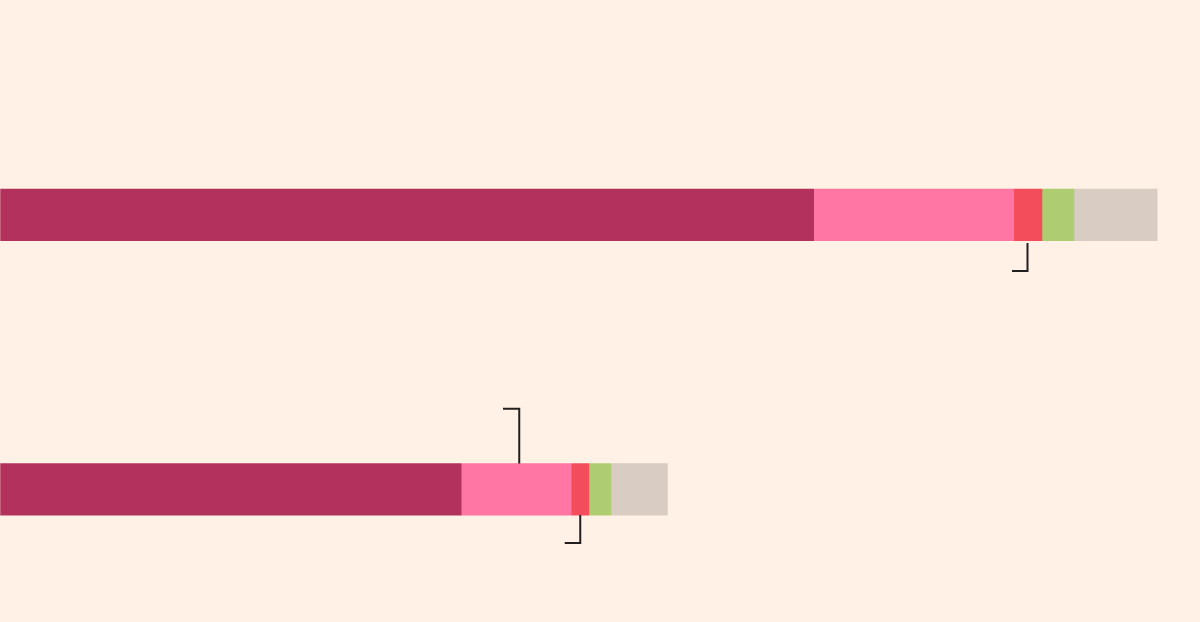

In the worst case of a magnitude 9.0 quake, close to land, Tokyo puts losses at ¥220tn ($2tn) for the first year alone. The amount is hard to imagine: 40 per cent of Japan’s GDP, equal to the market capitalisation of Apple, Microsoft, Berkshire Hathaway, ExxonMobil and Facebook combined. Around three-quarters of that is property damage, most of it privately owned, and the rest is lost economic activity.

“I think central government would need to pay about ¥100tn [$917bn],” says Mr Kawata. “In our committee, we listed about 30 kinds of social and economic damage, but we could directly estimate only 10.”

Damage to assets (in disaster area)

Land-side case1 (¥tn)

Buildings

119.1

Assets

29.3

Transport

4.7

Total: ¥169.4tn

Lifeline2

4.1

Other

12.2

Basic case

Buildings

67.5

Assets

16.1

Transport

3.2

Total: ¥97.7tn

Lifeline

2.6

Other

8.3

Damage to assets (in disaster area)

Land-side case1 (¥tn)

Buildings

119.1

Assets

29.3

Transport

4.7

Lifeline2

4.1

Other

12.2

Total: ¥169.4tn

Basic case

Buildings

67.5

Assets

16.1

Transport

3.2

Lifeline

2.6

Other

8.3

Total: ¥97.7tn

Damage to assets (in disaster area)

Land-side case1 (¥tn)

Buildings

119.1

Assets

29.3

Transport

4.7

Total: ¥169.4tn

Lifeline2

4.1

Other

12.2

Basic case

Buildings

67.5

Assets

16.1

Transport

3.2

Total: ¥97.7tn

Lifeline

2.6

Other

8.3

1: Where epicentre is close to shore

2: Utility supplies

A shock on that scale would likely cause a global recession. It could disrupt Japan’s long deflation — supply would fall sharply relative to demand — and is one of the few plausible triggers for a crisis over its gross public debt, which stands at 240 per cent of GDP.

Such risks are seldom factored into studies of Japan’s economy. Analysts from the International Monetary Fund to the financial markets assume a smooth path for Japan’s public debt.

“We don’t think about earthquakes in any formal way,” says Andrew Colquhoun, head of Asia-Pacific sovereign ratings at Fitch. “We make our baseline projection and look at risks around it.” But a big earthquake would be particularly hard to manage because GDP would fall at the same time as the reconstruction bill arrived.

One buffer is insurance, but the severity of earthquakes in Japan makes it hard to buy cover at a reasonable price; insurers paid $40bn towards the $210bn cost of the Tohoku disaster. For housing, a public reinsurance scheme can pay out a maximum of ¥7tn, although its current reserves stand at ¥1.2tn. Participation in the scheme is up to 29 per cent of households, from 9 per cent 20 years ago.

Reducing the damage

The potential scale of casualties from a Nankai earthquake means the focus is on saving lives. “How to survive a tsunami is the first priority. How to reduce economic damage is the second,” says Mr Kawata.

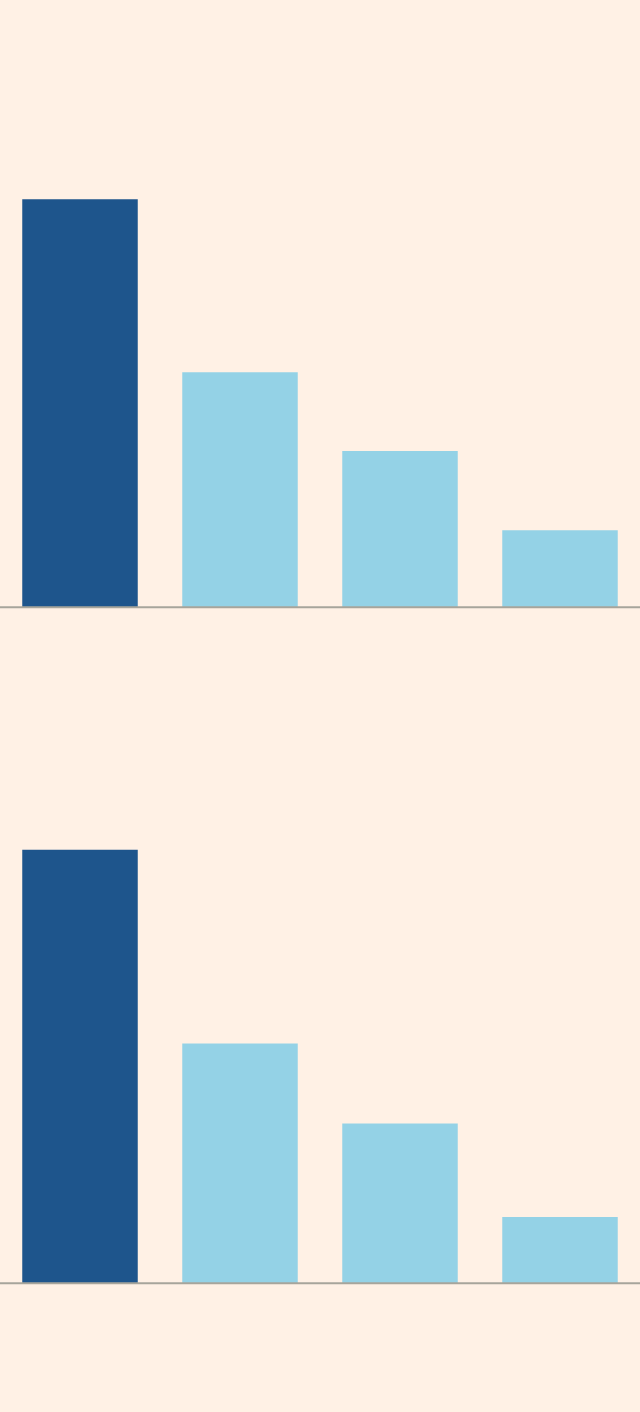

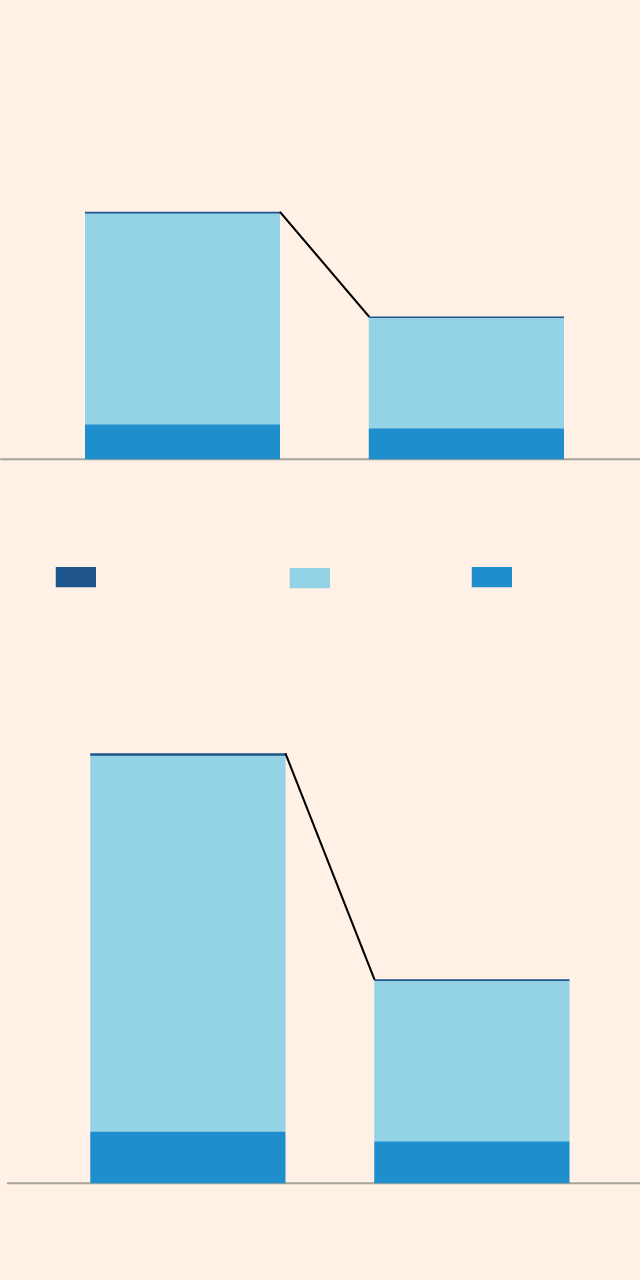

Saving of life

Buildings

Complete collapse due to quake

627,000

361,000

240,000

118,000

79%

90%

95%

100%

Earthquake resistance

Persons

Death by building collapse*

38,000

21,000

14,000

5,800

79%

90%

95%

100%

Earthquake resistance

* Midnight in winter

Saving of life

Buildings

Persons

Complete collapse due to quake

Death by building collapse*

38,000

627,000

21,000

361,000

14,000

240,000

118,000

5,800

79%

90%

95%

100%

79%

90%

95%

100%

Earthquake resistance

* Midnight in winter

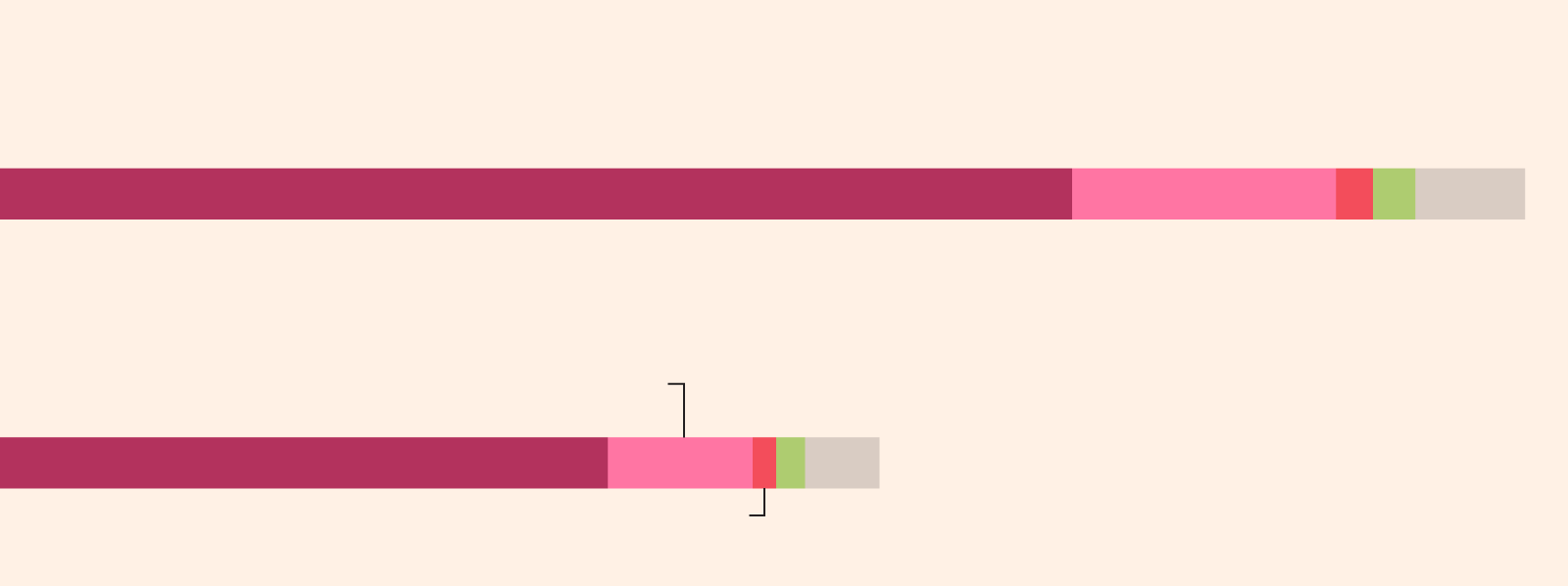

According to the government, the worst case casualty number of 323,000 could be lowered to 61,000 through a combination of swift evacuation and ensuring that all buildings are earthquake resistant, compared with 79 per cent of them now. It would not only save more lives but could halve the economic damage.

The 18,800 casualties in Tohoku, many of whom died despite the protection of seawalls, prompted a backlash against tsunami engineering. Under the slogan “from disaster prevention to disaster reduction”, some experts argue the focus should be on surviving and then rebuilding.

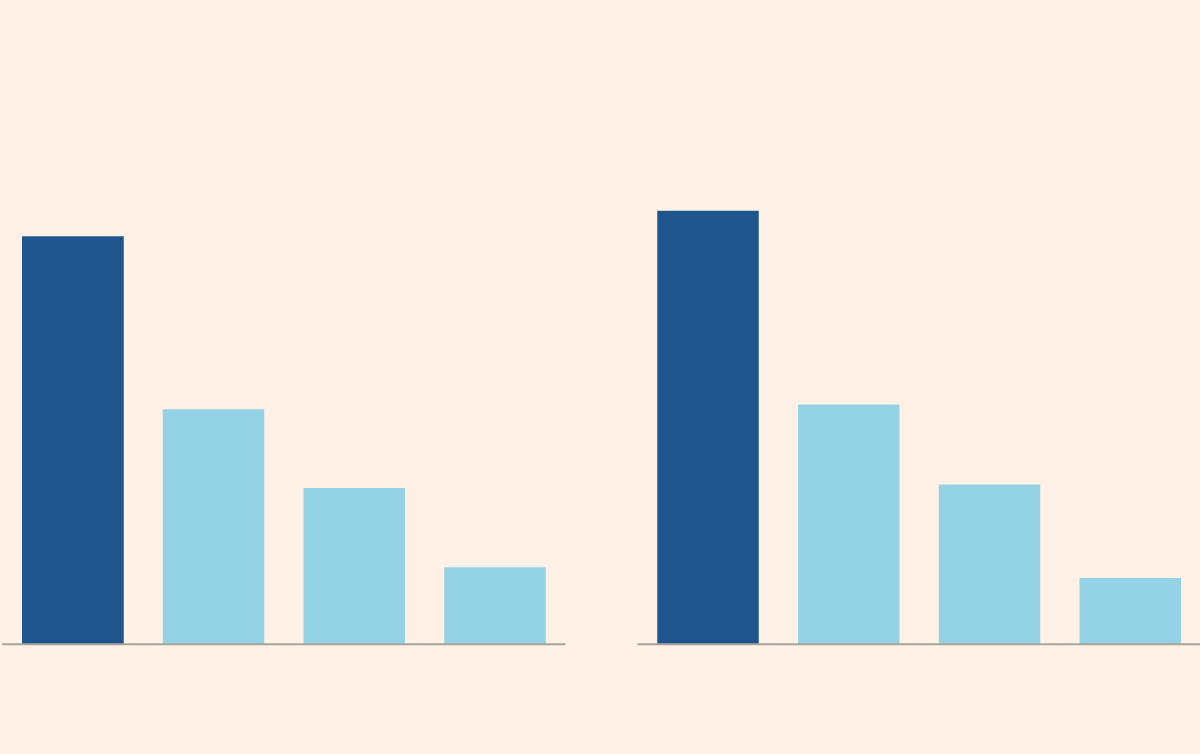

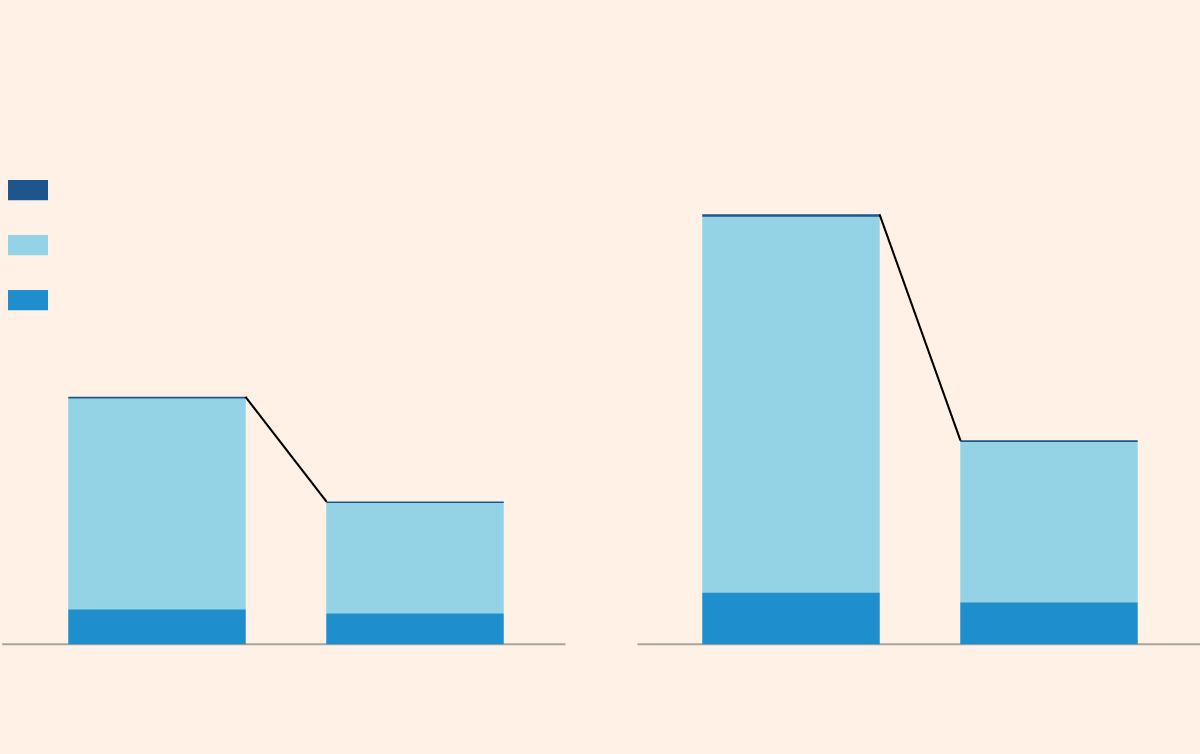

Cost of rebuilding

Basic case

¥ tn

0.6

83.4

42.5% REDUCTION

0.5

43.7

13.6

12.0

Without

With

Countermeasures

Public

Private

Semi-public

Land-side case1

¥ tn

0.9

148.4

52.6% REDUCTION

0.6

63.4

20.2

16.3

Without

With

Countermeasures

Cost of rebuilding

Basic case

Land-side case1

¥ tn

¥ tn

Semi-public

0.9

148.4

Private

Public

52.6% REDUCTION

0.6

83.4

0.6

42.5% REDUCTION

63.4

0.5

43.7

20.2

16.3

13.6

12.0

Without

With

Without

With

Countermeasures

Countermeasures

1: Where epicentre is close to shore

Mr Meguro argues that is short-sighted, saying: “A disaster that costs 40 or 60 per cent of GDP — there’s no recovering from that if you wait until afterwards.” Well-built seawalls make a big difference, he says.

The worst fatality rates in Tohoku towns were about 10 per cent, whereas historic records suggest fatality rates of half or two-thirds for unprepared fishing villages after a similar tsunami in 1896. In total, 97 per cent of people in the Tohoku inundation area survived.

That reflects the benefits of engineering, early warning and evacuation. Japan knows that one day another terrible earthquake will arrive — and if it is to mitigate against the impact of such a disaster, the time to act is now.

Sources: FT research; Japan Meteorological Agency; Nasa/Visible Earth; Disaster Management Bureau, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan