If you live in a big city, you may have thought about cycling to work. You will have weighed up the pros and cons: the health benefits, the low cost, the speed – versus the fact that you might be hit by an 18-tonne articulated lorry. On balance, you may have decided you didn’t want to take the risk.

You would be in the majority. In 2014, 64 per cent of people surveyed by the UK’s Department of Transport said they believed it was too dangerous for them to cycle on the road. These decisions are often based on gut feelings or anecdote: a friend who has had a great experience commuting by bike can inspire us to follow suit, while seeing or hearing about a bad cycling accident may put us off for life.

Such experiences are important. But what do the data say? As cities grow busier, obesity levels rise and climate change becomes a more pressing concern, we asked the FT’s transport correspondent and two of our specialist data journalists to investigate the risks and benefits of commuting by bike in big cities, something all of them do regularly. Here they give us their verdict: is it worth it?

Death and accidents

When a new cycle superhighway opened along London’s Blackfriars Road this year, a long-standing danger was removed. The traffic lights were phased so that cyclists didn’t have to go through the junction at the same time as motor vehicles.

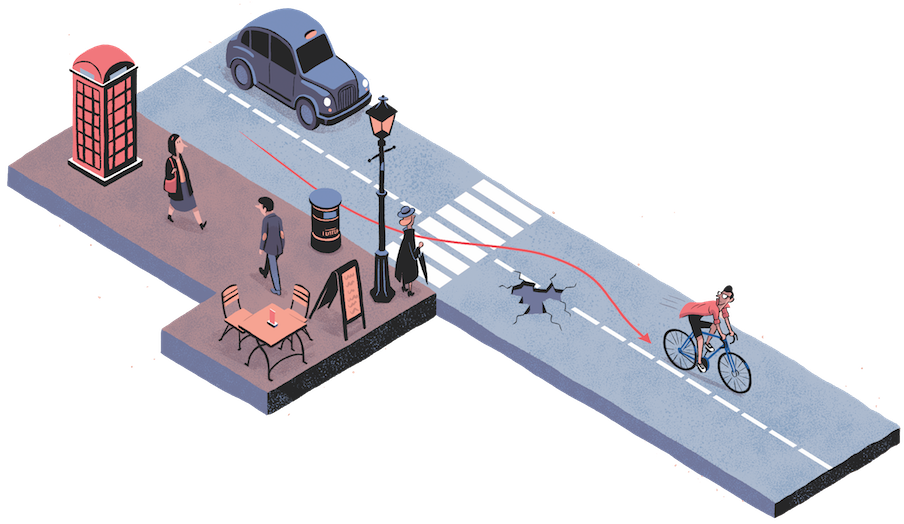

Nine cyclists died riding in London in 2015, all of them hit at intersections, highlighting the concentration of danger at these key pressure points. The designers of London’s new cycle superhighways have made safer junctions a priority. Transport for London, the government agency responsible for the capital’s transport system and the creator of superhighways, is also pushing truck operators to introduce new types of lorry with better visibility, because big trucks are involved in a disproportionately high number of crashes affecting cyclists.

These steps are typical of the efforts under way across the industrialised world to make urban cycling safer. Policy makers hope that, by providing better spaces for cyclists to use, they can encourage the growth of a clean, low-cost transport mode that will take some strain off existing transport systems.

“What we know is that the single biggest thing which deters non-cyclists from cycling is the fear of being injured by a car or a lorry,” says Ben Plowden, a senior director of planning at TfL.

Mile by mile, people in the UK are actually more likely to die walking than cycling, according to figures from the Department for Transport. For every billion miles cycled last year, 30.9 cyclists were killed, while 35.8 pedestrians were killed for every billion miles walked. Both activities are significantly safer than riding a motorbike – 122 motorcyclists are killed for every billion miles driven.

Of more concern are the statistics around injury. The UK’s overall casualty rate for cyclists, a broader measure which counts serious injuries and slight injuries as well as deaths, was around 5,800 per billion miles in 2015, not far off the casualty rate for motorcyclists – and almost three times higher than the 2,100 per billion miles for pedestrians. As well as cutting the fatality rate, TfL hopes its safety improvements can reduce the rate of injuries.

The front rank of cycle-safe cities worldwide are in northern Europe. City Cycling, published in 2012 and edited by John Pucher and Ralph Buehler, calculated the average number of annual cyclist deaths over the previous five years for every 10,000 daily cycle commuters in big European and American cities. London, with an average of 1.1 deaths per 10,000 commuters, fared better than New York’s 3.8. But both lagged far behind the 0.3 annual average deaths in Copenhagen and 0.4 in Amsterdam.

Simon Munk, infrastructure campaigner for the London Cycle Campaign, says the evidence suggests cycling is higher in cities with safe, segregated lanes and well-designed junctions. While cyclists in London still enjoy only patchy areas of segregation from traffic, their counterparts in Amsterdam and Copenhagen often spend their whole commutes isolated from cars.

Patchy information in the industrialised world makes it hard for statisticians to be more precise than Pucher and Buehler. Data for cities in the developing world – such as Delhi and Beijing – are still more incomplete. “In the cities where people feel under threat, they probably are under threat,” Munk says.

New York and many other world cities are planning similar road improvements to London to increase cycle safety. Paul Steely White, executive director of Transportation Alternatives, a cycle-advocacy group, says his organisation has worked with New York’s Department of Transportation to devise plans for safer junctions. Michael Schenkman, 78, hit in Bayside, Queens, on August 24, became the 16th cyclist to die in New York this year. Such tragic deaths tend to be concentrated, White says, on the city’s periphery, much of which lacks specialist facilities for cyclists, while traffic is heavy and fast-moving.

Some people may never be tempted on to their city’s roads until cycle paths are entirely separate, as in many parts of the Netherlands. In more than 20 years of urban cycling in the UK, I have been knocked off by motor vehicles twice and once by another cyclist. It was only by good fortune that I escaped serious, long-term injury. But the bald facts of those incidents fail to capture anything like the whole, complex picture of the risks I’m taking. Heart disease, cancer, stroke and a tendency to put on weight all pose far more serious risks to my life expectancy than the relatively small risk of a fatal crash.

All forms of transport entail some risk. I was knocked down as a child while crossing a street. I crashed my dad’s car off the road during my first driving lesson. I’ve been caught underground in a subway train during a track fire. Riding a bicycle represents, even under current sub-optimal conditions, a good trade-off between risks and rewards. And as urban design becomes more protective of cyclists, that trade-off can only improve.

Pollution

On a recent London commute, I was surprised to see what looked like the villain from the post-apocalyptic film Mad Max: Fury Road at the lights near Southwark Bridge. I belatedly realised the cyclist was simply wearing a state-of-the-art anti-pollution mask.

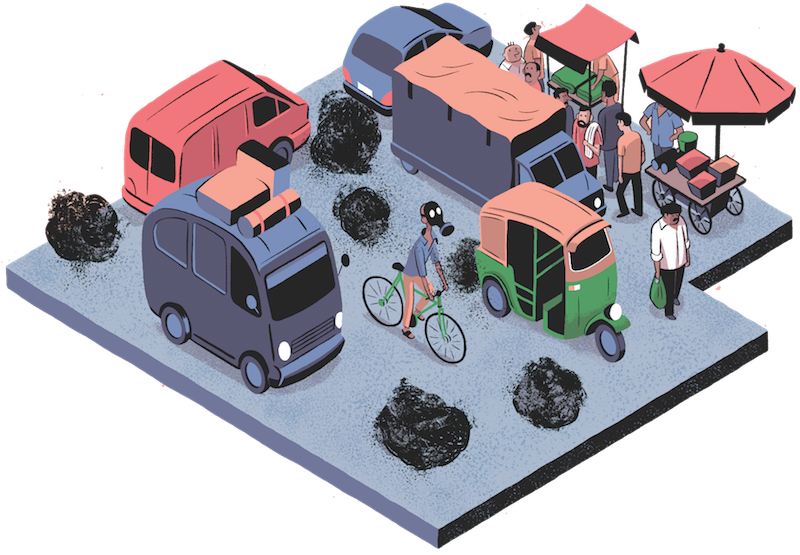

Who could blame him for protecting himself? London’s air pollution, which is caused primarily by traffic and diesel fumes, is responsible for 9,500 premature deaths each year, according to a 2015 study by King’s College, London. As a result of their proximity to a parade of exhaust-emitting cars and lorries, cyclists can expect to be exposed to higher levels of carbon monoxide, ozone and nitrogen dioxide than pedestrians. Not just that, but because cycling is more physically demanding than walking, cyclists breathe more heavily while on the road, which means inhaling more fine particulates.

Researchers from the London School of Medicine looked into this issue in 2011. According to their findings, bicycle commuters inhale more than twice the amount of black carbon particles as pedestrians making a comparable trip. The only way to reduce this is to avoid traffic hot spots by taking alternative routes wherever possible.

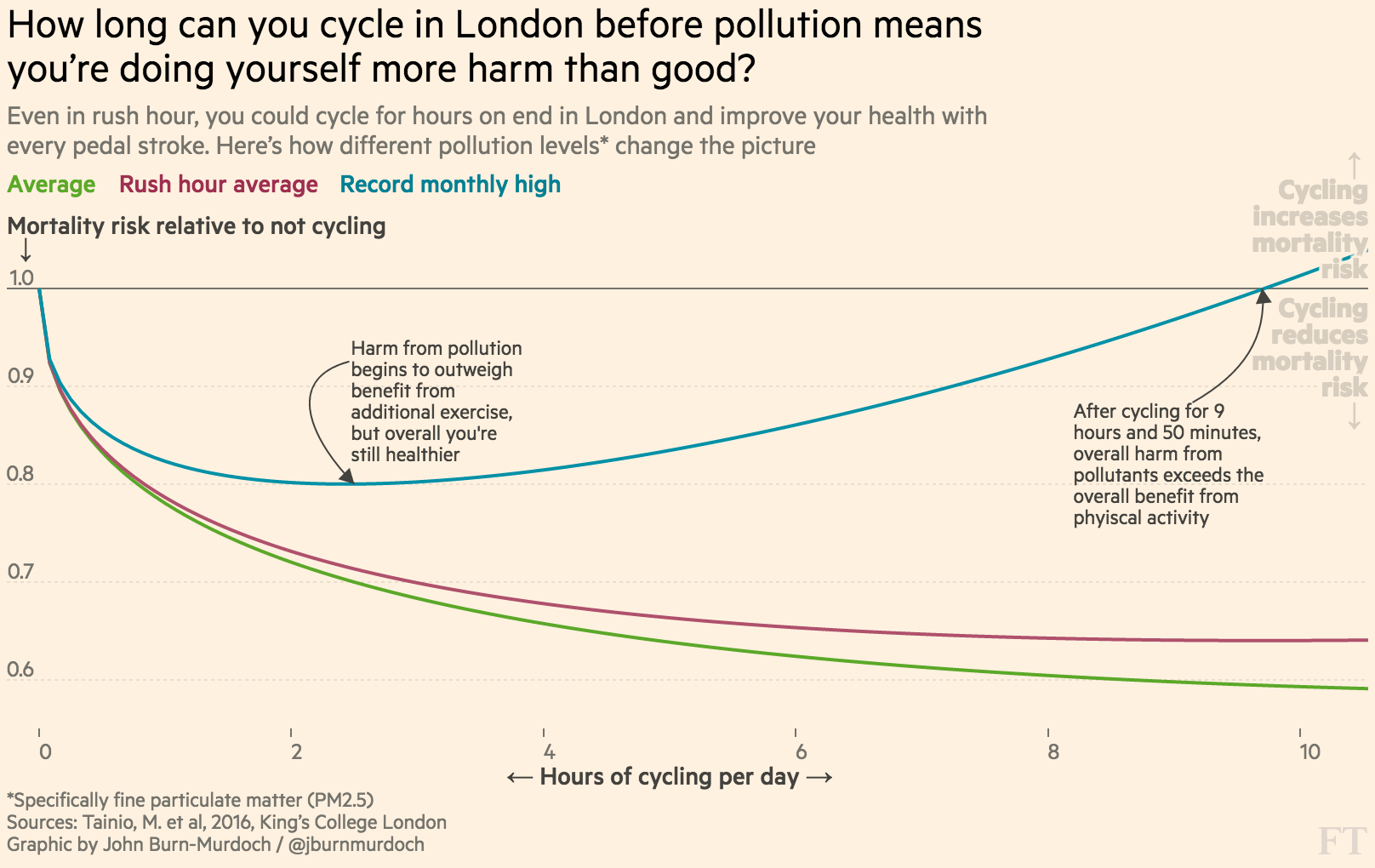

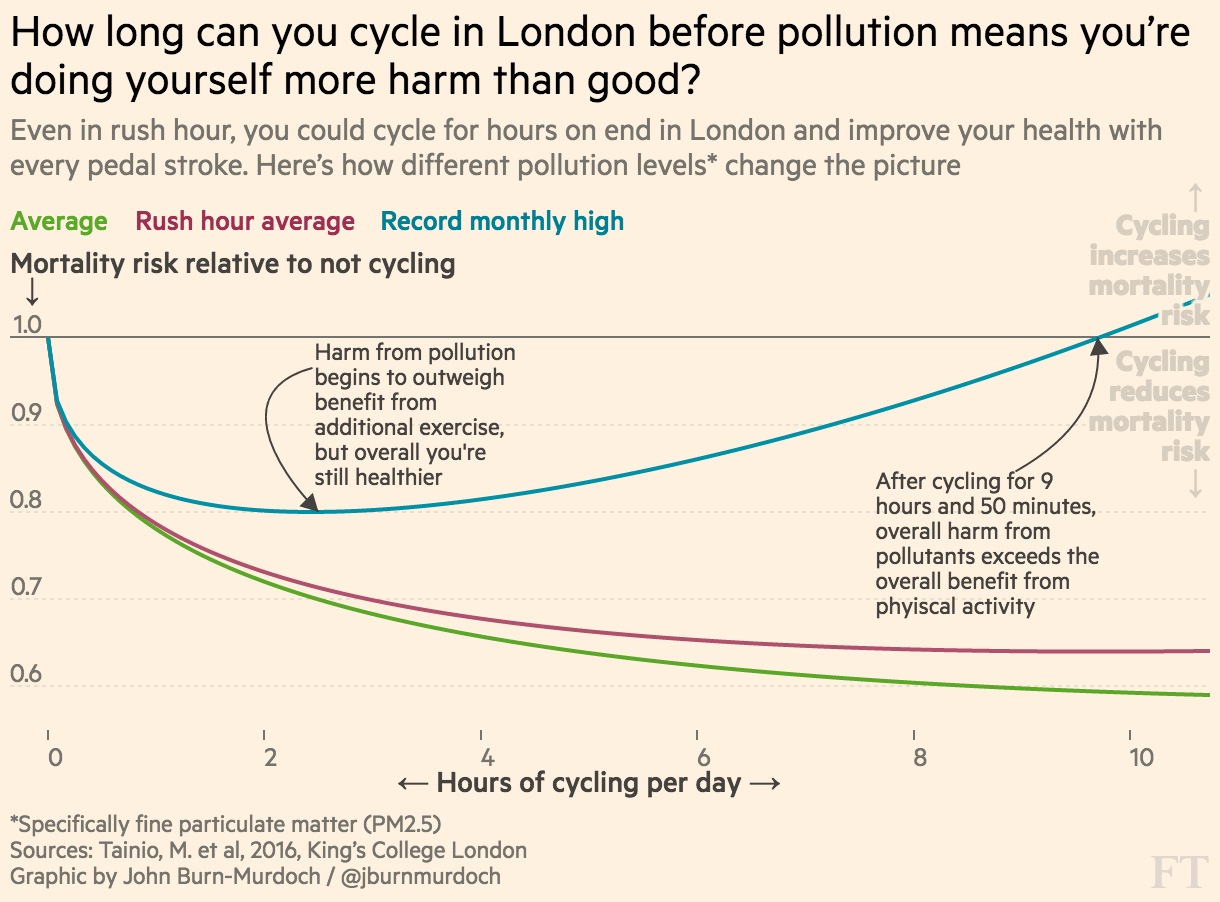

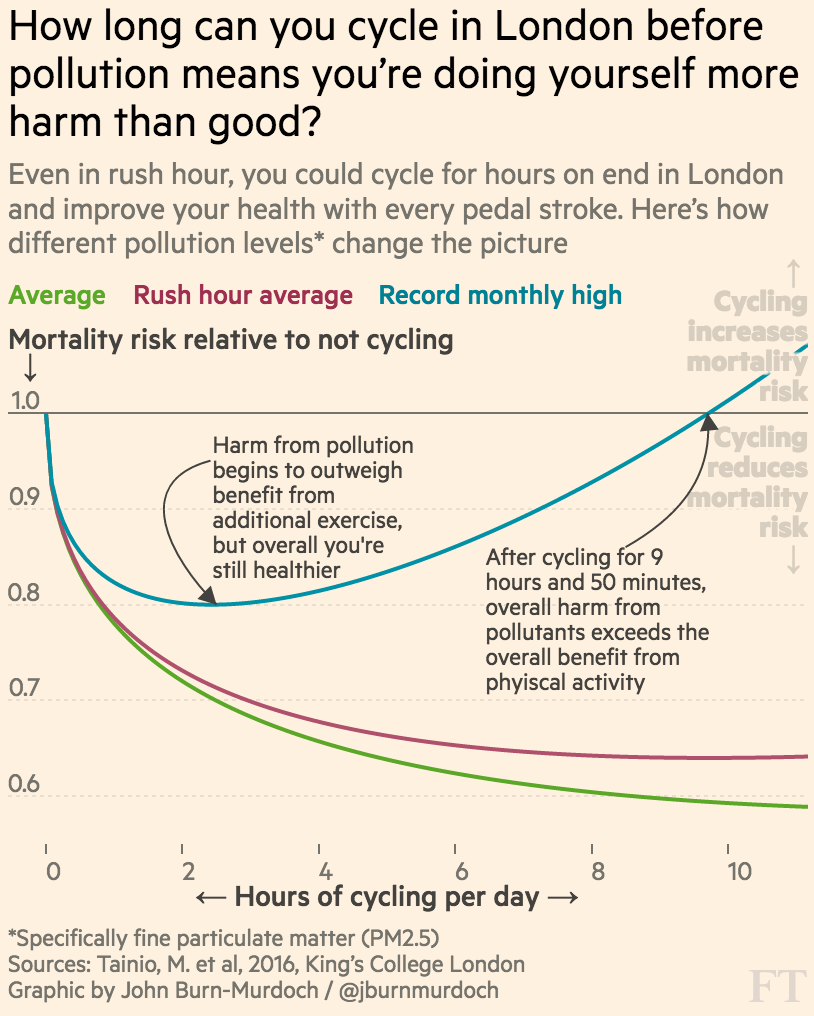

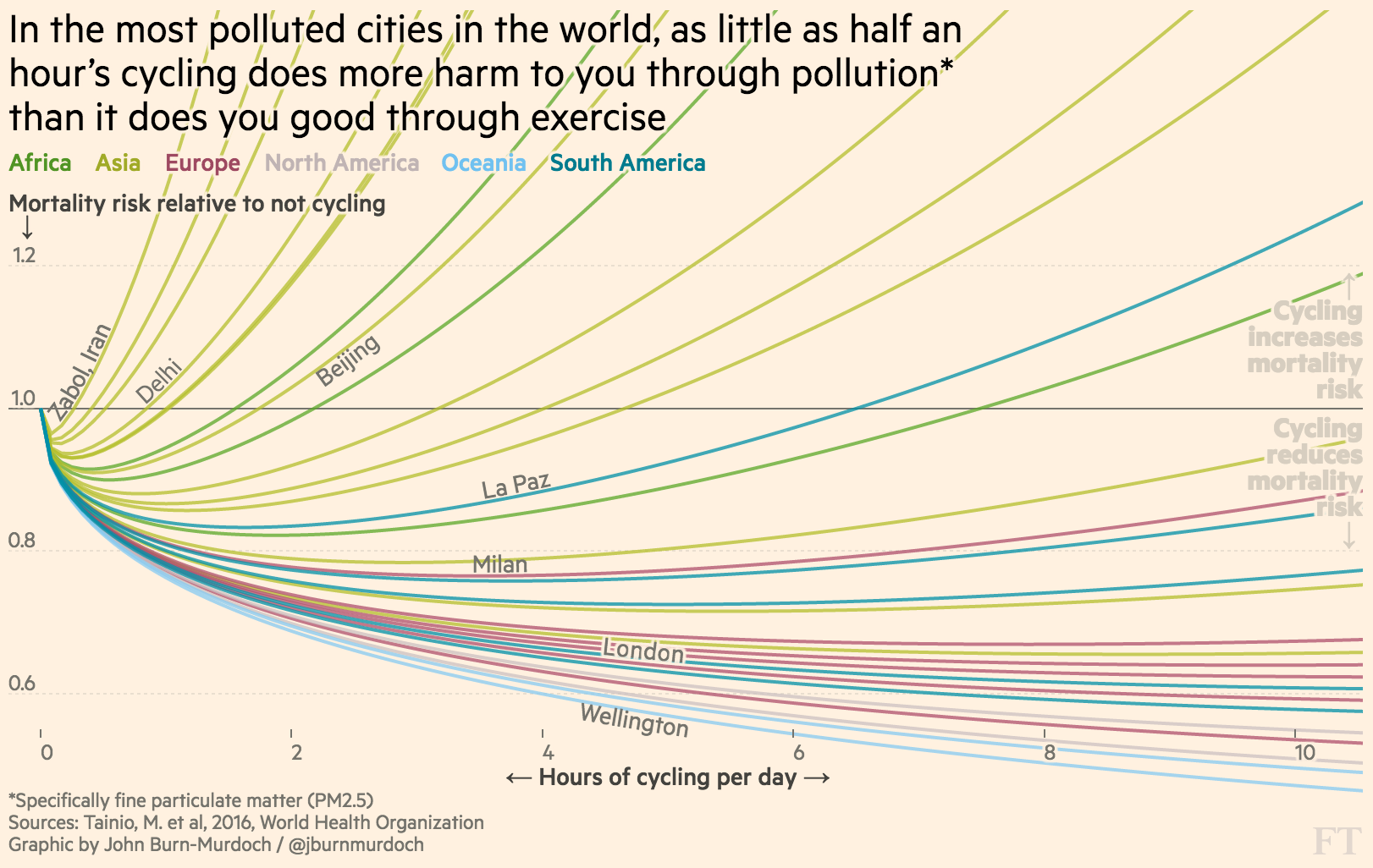

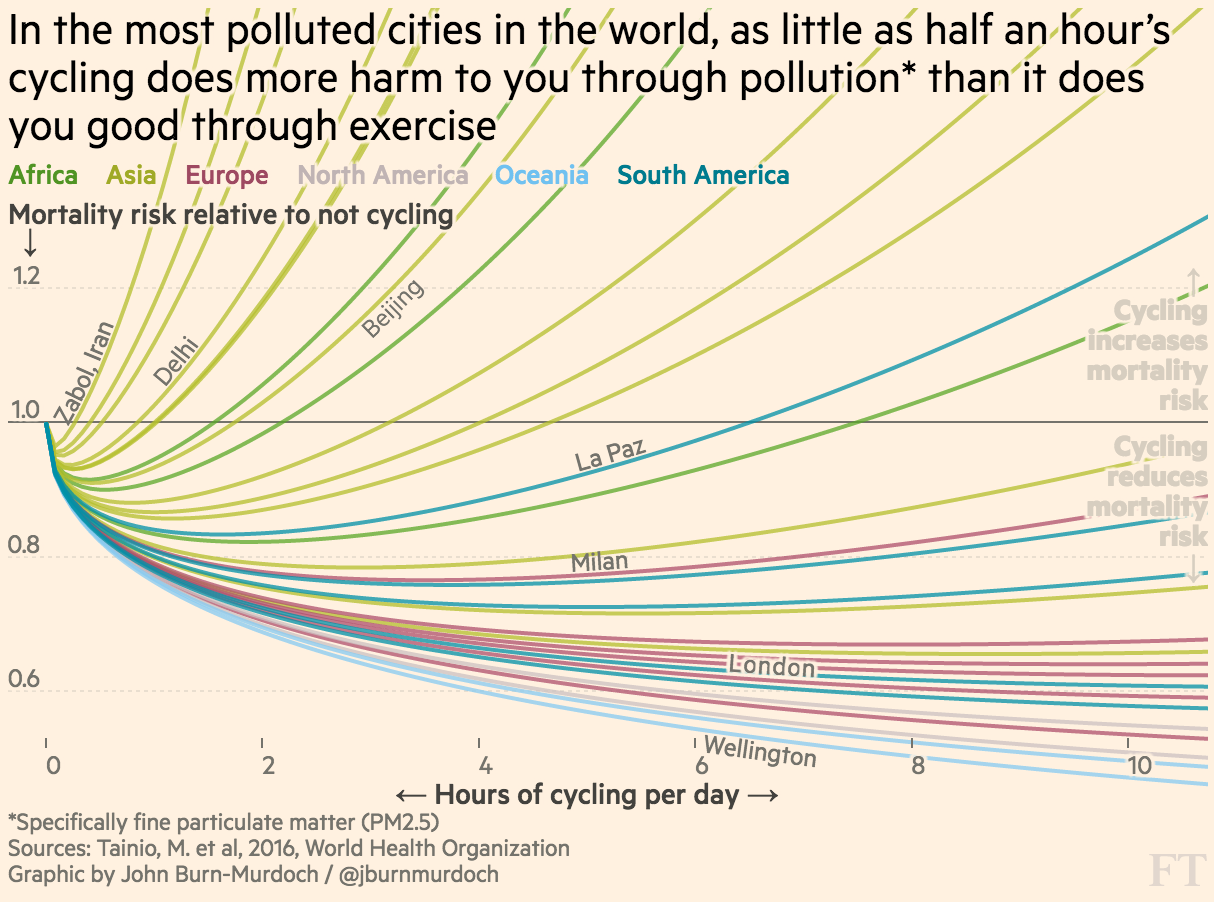

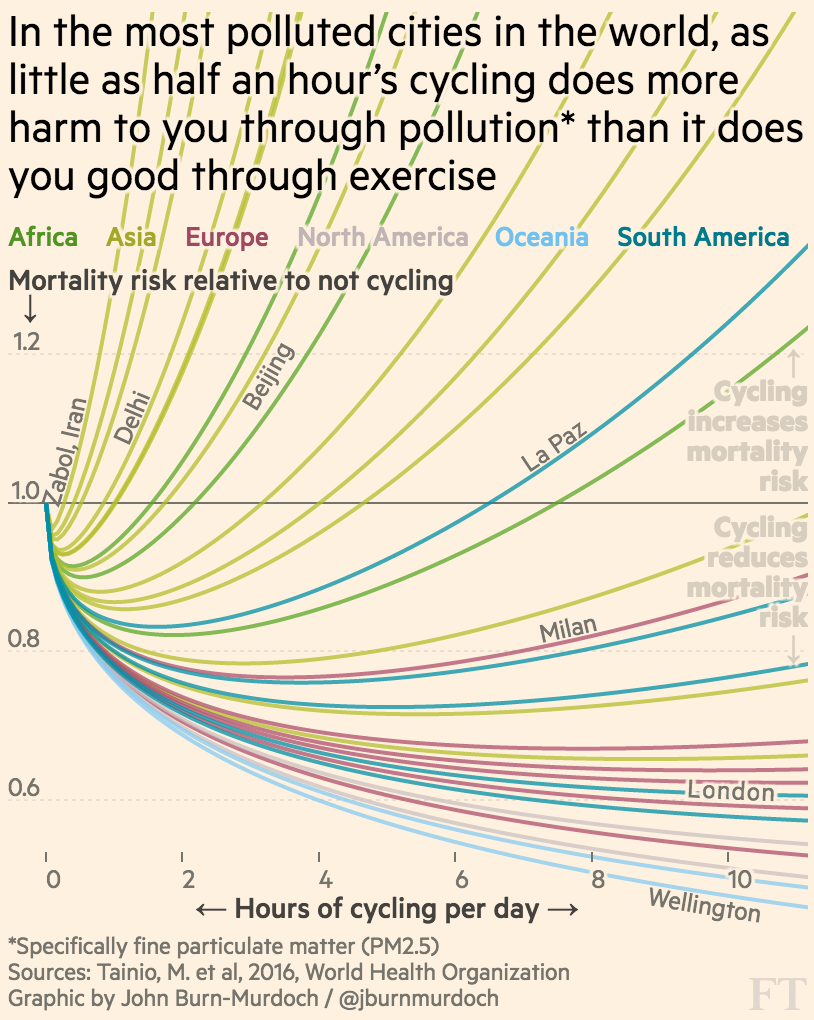

As a cyclist, the stink of petrol fumes as you sit in traffic behind a lorry can be deeply off-putting, but it’s worth putting the issue in perspective. A recent study by Cambridge University found that the health benefits of cycling – as well as walking – outweigh the risks caused by air pollution in 99 per cent of cities.

After examining the different levels of air pollution in thousands of cities in the world monitored by the World Health Organisation, the researchers established a tipping point – the length of time after which there was no further health benefit, and a break-even point, when the harm from air pollution began to outweigh the health benefit.

“Even in Delhi, one of the most polluted cities in the world – with pollution levels 10 times those in London – people would need to cycle over five hours per week before the pollution risks outweigh the health benefits,” says Dr Marko Tainio, who led the study. In London you could cycle for hours on end every day. The worst city in the study is Zabol, in Iran – but the high level of particulates in the air there is caused by dust storms, not exhaust fumes.

This is not to say that air pollution is harmless, and indeed more needs to be done to tackle the problem at the root. For people who suffer from asthma, have heart conditions or respiratory issues, it’s a serious concern. Cyclists can consider arming themselves with a Mad Max respiratory mask, take quieter routes – and keep the broader benefits in mind.

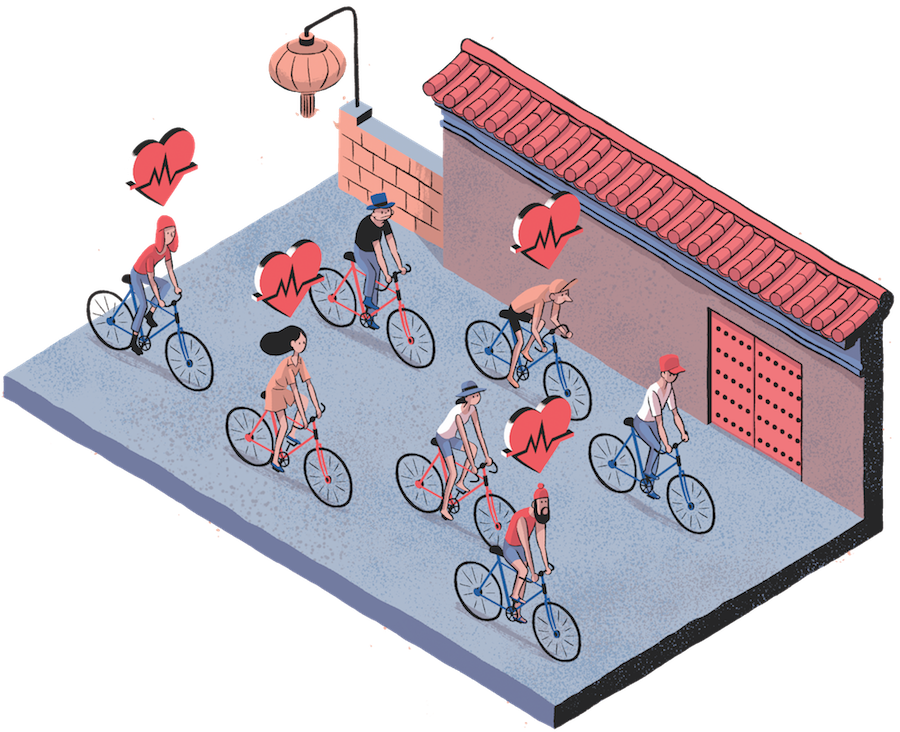

The health benefits

The risk of serious injury from road accidents is elevated for cyclists compared with car drivers and pedestrians – so is the safest thing to avoid travelling by bike altogether? A broad base of evidence says no. On a population level, the dangers you face are offset by the many benefits associated with an active commute, which will translate for most people into increased life expectancy overall.

I pedal to work come rain, shine or hail, but of course the decision to cycle is an individual preference. What are the arguments in favour of cycling? As the aphorism goes, the best nutrition or exercise regime is not the most extreme, but the one that you can stick with. There can be few better – and easier – ways of doing this than by incorporating physical exercise into an activity you are contractually obliged to do.

Not only is an active commute practical, there is evidence that for some it may be crucial. Official bodies recommend around half an hour of moderate aerobic activity per day for maintaining general health, but multiple studies have shown that even this baseline level of exercise does not always prevent weight gain.

Regardless of individual circumstances, moving beyond the basic recommendation of 2.5 hours of aerobic exercise per week has consistently been shown to impart additional reductions in the risk of cardiovascular disease. For many people, going beyond half an hour per day may mean they simply do not have enough leisure time to fit in sufficient exercise, with the corollary that the additional activity must be built into the working day.

Compared with other forms of exercise, cycling has two objective points in its favour. First, convenience, in the form of speed. If we take 30 minutes as a conservative upper limit on how long the average person would want to spend travelling to or from work under their own steam, few busy professionals are lucky enough to be within a truly walkable distance of their workplace.

The maximum reasonable commuting distance under an individual’s own steam is 1.5 miles; jump on a bike, however, and that figure escalates to six miles, all without breaking into the kind of sweat that might necessitate specialist, body-hugging gear or needing to shower and change at the office.

A steady run to work may be a more intense workout than a steady cycle – an 11-stone person, running at a nine-minute mile pace (6.7mph) burns just over 400 calories over half an hour, compared with about 300 for a cyclist at 12mph. But pounding the pavement can take its toll on your knees in a way that the more fluid motion of pushing the pedals won’t.

How long could you cycle in your city before the negative impacts of pollution would outweigh the benefits of exercise?

You could cycle before harm from pollution would outweigh the health benefits from exercise

Do you cycle to work?

We would like to know what you think about urban cycling. Instagram a photo of you and your bike on your commute, telling us why you choose to travel by bike OR your favourite cycle route, and tag @ft_weekend. We may publish a selection of entries on FT.com