Armani Adams-Smith lives in Brooklyn, New York — she is Brooklyn, she says.

She is 10 years old, tall and lean, whip-smart and popular. She likes to look “fly” but she doesn’t care much about “pretty”. She has a “mortal enemy”, a chubby, bespectacled boy named Theodore: “You get me tight, Theodore; you get me real tight, bro.”

Ask her why she’s not worried about the upcoming standardised tests that will help determine where she goes to middle school, or why she can beat the boys in gym class, or why she cold-called a local rapper to ask if she could appear in her music video, she has a simple answer: “I’m Armani Adams-Smith.”

Armani (centre), with her mother, Arlene, and sister, Jameeyah, outside their home in Brooklyn

When Armani was four years old, her mother, Arlene, went to prison for 18 months and Armani and her younger sister, Jameeyah, joined the ranks of at least 5m children in the US (roughly 7 per cent) with a parent who has been incarcerated.

Being an adolescent girl is hard anywhere. Globally, a quarter of a billion girls live in poverty and development workers consider the period between the ages of 10 and 19 as a crucial window in a girl’s life. These are the years when decisions are made and behaviours established that can either help a girl to flourish or restrict her horizons for good.

But while America’s development dollars have often been channelled towards projects in the developing world, girls closer to home like Armani are still at risk of slipping through the cracks.

By many socio-economic measures, black America still resembles a developing country: nearly 40 per cent of African-American children live below the poverty line, according to the Pew Research Center, compared with about 11 per cent of white kids. A black girl like Armani is more likely than her white peers to be suspended, expelled or end up in the juvenile justice system.

African-American children are most likely to have had parents in jail. Nationally, one in four will have had a mother or father imprisoned by the age of 18, compared with one in 10 Latino children, or one in 25 white children. Children of jailed parents are more likely to be sent to prison themselves, according to a 2015 report by the non-profit Child Trends, and to live with people suffering from mental illness or substance abuse.

So Armani has more than her fair share of challenges to overcome — and she knows it. Her understanding of how her race and gender will shape her life is informed by experience: she sees that white people are moving into the area around her school, but that their kids do not seem to enrol at PS 256 Benjamin Banneker. She knows that one reason she quit the school basketball team was because she was the only girl.

Arlene and her daughters outside their school in Bedford-Stuyvesant

She also senses that the new Trump administration could threaten her future. “Now Donald Trump is president, we’ll have different things taken from us — financial things, medication, insurance — black people are going to have things taken from us,” she says.

Still, Armani is undeterred. She nonchalantly rattles off her many career goals — “a basketball player, an author, a producer and a director and an actor” — and displays a 10-year-old’s ability to shift between subjects weighty and light.

“My challenge is, like, my skin colour and, like, my education, because different people around the world, they don’t think girls should get education. Oh... and [to be] a girl playing basketball — that’s the number one of these challenges.”

The Adams girls are luckier than some. Each day after school they are bussed to Children of Promise (CPNYC), the only after-school programme in New York City dedicated to children whose parents have been to jail.

Resources for kids like Armani and Jameeyah are scarce at the local, state and national level. The National Resource Center on Children and Families of the Incarcerated, at Rutgers University, lists about 100 groups in its national database of vetted programmes. This amounts to just a few per state — in some states there are none at all.

Children of Promise is one reason Arlene kept the girls at their old school in the neighbourhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant, even after the family moved a 50-minute bus ride away to Ditmas Park in 2015. The programme is central to their lives. Along with tutoring, games and sports, CPNYC offers therapy with licensed clinicians for the 350 children who attend each year — and helps parents as they try to get back on their feet.

Chantal Arthurs has been Armani's counsellor since she was seven years old

Armani’s friends at CPNYC are her “real friends”, she says, because they can relate to her life: the monthly jail visits, the trauma of abandonment and the fear that people at school might find out.

“It’s pretty hard at school,” she says. “Like you can’t really tell them nothing — you can’t really tell them how you feel. Here it’s like a safe zone where you can express how you feel in any type of way. Yes, it’s a safe zone here.”

Even so, there is something Armani would prefer her “sisters” at CPNYC did not know: Arlene went to prison because she killed Armani’s father. One night in September 2010, she stabbed Jamel — known as Mel — in their apartment.

It was an accident, Arlene says. Mel was drunk, demanding sex and beating her. She grabbed a knife for protection and, when the blows became too much, she inadvertently swung the blade. She called 911 and kept pressure on the wound. Mel died on the way to the hospital. Arlene was arrested.

Armani attends Children of Promise, an after-school programme for children of parents who have been incarcerated in New York City

Arlene’s adolescence was very different from the one she wants for her daughters. She met Mel as a teenager. They grew up across the street from each other and started dating after Arlene, at the age of 14, began selling crack cocaine for a local drug dealer.

She dropped out of high school at the age of 17 when she discovered she was pregnant with Armani. The couple sold drugs together, and were kicked out of Arlene’s mother’s apartment after a police raid. They later lived on their own or in homeless shelters.

Domestic abuse was a constant of the relationship, both before and after the birth of their daughters. Arlene was not a stranger to that kind of violence. Her own mother had left her abusive husband when Arlene was 11.

Armani talks about the lessons her mother has taught her

Arlene believes Armani is exceptional — “she’s maybe a kid I wish I could have been when I was her age” — but her greatest fear is that Armani will be sucked into the same cycle of bad relationships, domestic violence and early pregnancy that she suffered.

The US teen pregnancy rate for African-American girls in 2014 was double the white rate at nearly 35 per 1,000, according to government data.

So she tries to be open with her daughter about the risks: “Armani doesn’t need to learn about drugs outside because I talk to her about drugs; she doesn’t need to learn about sex outside because I talk to her about sex.”

For Jameeyah’s ninth birthday, Arlene has thrown a Nicki-Minaj-themed party in the family’s cramped attic apartment. The rapper-singer’s music videos play on the television and the walls are papered pink. Impromptu, hair-whipping dance routines break out among the diminutive party guests.

The girls’ godmother Robi is in a pink tutu, playing the nail polish fairy. The kids drink Western Beef brand cola, orange soda and ginger ale and dine on cut-up hot dogs, spaghetti and meatballs. There is chicken in the oven for later.

Armani with friends at Jameeyah’s birthday party in Ditmas Park

During the 18 months Arlene spent awaiting trial on Rikers Island, Armani and Jameeyah lived with their grandmother. Arlene told the girls that she was in college and that their father had died of an illness.

She was eventually offered a plea deal (admit to manslaughter and go free with five years’ probation). But even after Arlene was released, in March 2012, the family remained separated. Her mother’s landlord would not let Arlene live in the apartment after the 2009 police raid, so Arlene spent the girls’ waking hours with them and left at night, after they went to bed, to sleep in homeless shelters, with friends or on subway trains.

It was Armani’s mentor at CPNYC that helped find the money Arlene needed to secure the lease on their current home in Ditmas Park. The family still struggles to get by on the $12-an-hour Arlene makes in her part-time job as an assistant at the city college she attends, with help from Kay, her boyfriend of just over five months, who works in maintenance at the same school. But they make it work.

Armani and Arlene perform Mr Telephone Man by New Edition as Kay looks on

When she graduates from college, Arlene wants to work as a counsellor and advocate for women like her. She is trying to teach her children about empathy, understanding and mental health — a problem that is often ignored in the black community, she says. She does not demonise Mel, whose photographs hang in the apartment, one above Armani’s bed.

“People never understand, but regardless of what Jamel did to me, that’s my children’s father and I never meant for that to happen to him,” she says.

The girls take two city buses to get to their elementary school. As the 103 rolls downtown, Armani lays out a series of events that will result in her ultimate dream: hanging out with the rapper Drake.

Step 1: “What if Rondae Hollis-Jefferson [the basketball player] sees me at the Nets game?”

Step 2: “And what if he remembers me [from the day he was doing an event at a local Target store and posed for pictures with Armani] and invites me to the locker room?”

Step 3: “What if he introduces me to [rival player] Russell Westbrook?”

Step 4: “What happens if I talk to Russell Westbrook and he gives me his number? I bet I’ll get it.”

“Next thing you know I’m at Drake’s house.”

Arlene asks that she not forget the little people. “I won’t forget you,” Armani replies, “I’ll send you money, but y’all can’t come to Drake’s house.”

Armani and Jameeyah ride two city buses for nearly an hour to get to school

At times, it is difficult to tell whether Armani is serious about meeting Drake. But she is part of a generation for whom fame seems attainable in a way that it never was for their parents. Like many kids her age, she thinks a lot about social media: “Facebook is for old people,” she says. Instead, her life is dominated by Snapchat and the video social network Musical.ly.

Most days, Armani can rattle off her exact number of Muscial.ly followers (it was 1,211 in early May) and ‘hearts’ (27,345). The app lets users create short videos of themselves lip-syncing or dancing to hit songs. Most of Armani’s involve her holding her phone, selfie-style, rapping to songs by Drake.

Arlene talks about the early years of Armani’s life

Armani has had to mature faster than many kids. She is often torn between the silly games of childhood and the gawky self-consciousness of adolescence. She is at an age now where she will soon leave childhood behind, when boys appear — talking, teasing, hitting. But she is holding tight to the past.

Despite ageing out of the group, she asked her counsellor at CPNYC if she could stay with the 8-9 year olds for another year. Chantal Arthurs, who has been Armani’s counsellor since she was seven, agreed because, “she’s not as exposed as the other 10s — she doesn’t curse, she’s not vulgar. She’s a really good influence on the younger girls — [she shows them] that you can be a girl and be good at math, or love reading, or be good at sports.”

At school, though, to the consternation of her teacher, Armani delivers her answers quietly, as if they were questions. “Honey, I keep telling you, you’re smart,” the teacher says. “Have confidence in your answer.”

At CPNYC one afternoon, Armani walks past a girl sitting at the next table and points at her, mouthing-but-not-really, “I don’t like that child.”

The girl is a family friend and last year, in what Armani considers an unforgivable act, she revealed to a busload of kids what really happened to Armani’s father. One of those kids was Jameeyah, who did not yet know the whole truth.

“She told my best friends my business and I felt like she betrayed me, so I don’t ever want to make that mistake again,” Armani says.

Armani and Kay at a basketball game

Armani misses her father. Arlene says she has his face, his nose, his frame, “his everything. She has that asshole thing about her — that confidence, that’s Mel.”

Arlene started dating Kay last year and Armani can be mercurial when it comes to the new father figure in her life. When he takes her to watch a Brooklyn Nets game, she leans into his shoulder, giggles at his jokes and tries to make him laugh. Kay finishes his bag of popcorn and Armani passes him hers without a word.

They see each other nearly every day, but when he is not around she will say things like, “I don’t want a stepfather”. It is painful for Arlene and difficult for Kay.

The family at an indoor bouncy castle park on the anniversary of Mel’s birthday

Chantal Arthurs says that many kids in Armani’s situation sink into depression or develop behavioural problems, but that Armani “understands what happened without letting it affect her daily life. She doesn’t blame it or use it as an excuse.” For now, at least, Armani is making great strides.

Back at the gym at CPNYC, Armani is shooting half-court shots over a group of her friends, who are hula-hooping and dancing in front of the basket. Suddenly she makes one and looks around astonished. No one is watching. She does half a victory dance and then catches herself. A smile flashes across her face — proud, sheepish, then proud again.

She tosses another one up.

Xie Yaqi is 12 years old.

Her English name is Eva. She carries it like a talisman; it reminds her of her favourite teacher back in the big city — and of her father. She has not seen her parents in two months.

Eva’s short life has straddled two worlds. Until she was seven, she was raised by her grandmother in the rural Pingshang township, while her parents moved between jobs in Guangdong province, the growth engine of China’s manufacturing industry. As soon as her father got a good enough job, he brought Eva to live with her mother and younger brother in the city and paid for her to attend a private school.

But last September, Eva’s father was forced to send his daughter back to the backwater he thought they had escaped.

Eva in her family home in Pingshang township, Hunan province

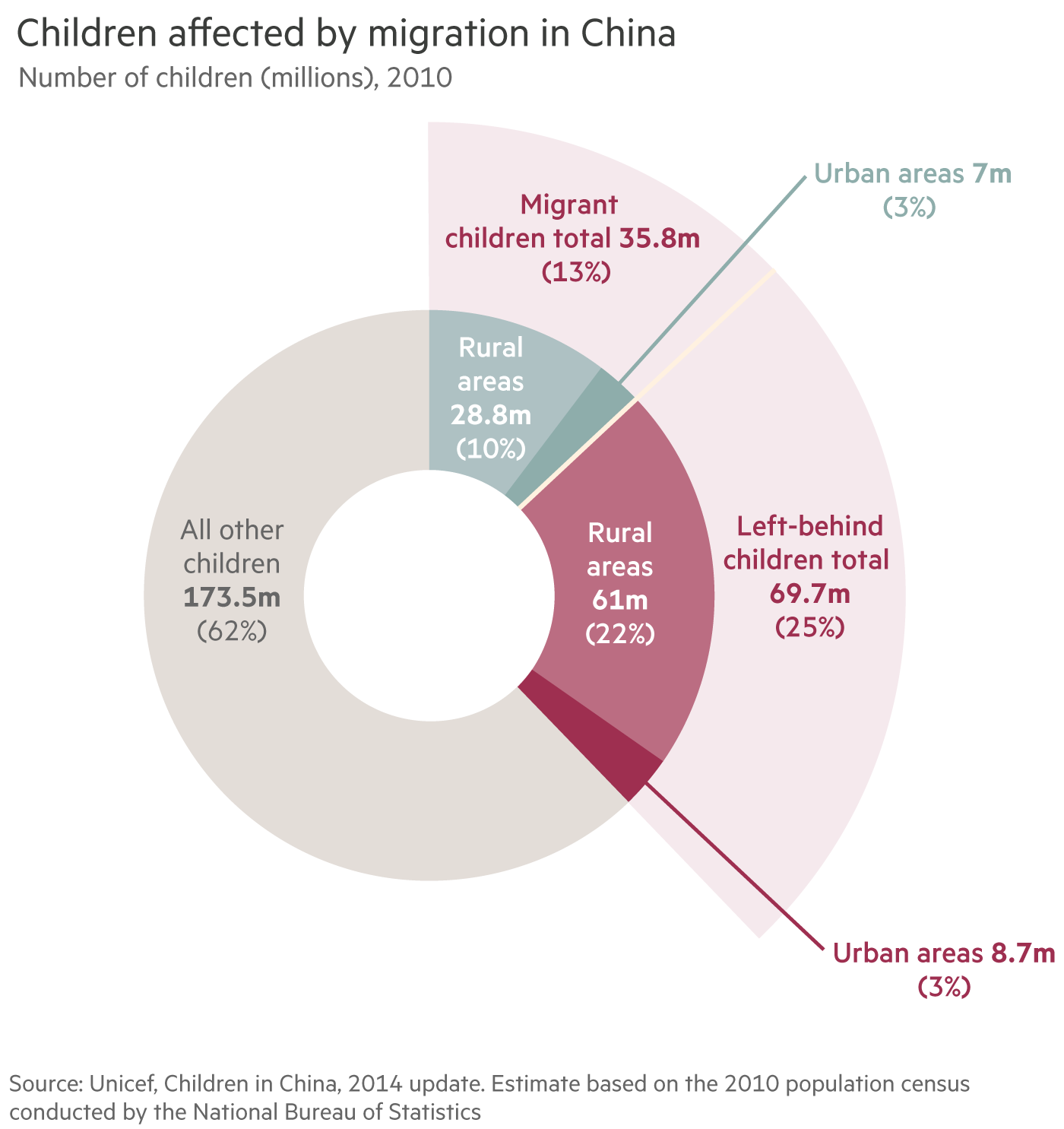

Eva is one of about 70m Chinese children who live apart from their parents, as of the latest national census in 2010.

More than 281m men and women have moved to China’s cities since a mass migration began 40 years ago — the largest and fastest shift in history. Some of their so-called “left-behind” children have never left the countryside. Others made it as far as the city but could not follow when their parents moved on again. And still others, like Eva, were brought to the city only to be sent back again.

“I begged my mother to let me stay,” Eva says. “At first she agreed, but then my father didn’t have enough money. School fees over there are expensive. Actually, my mother tricked me into coming back... she said I should visit my grandmother for the summer. I missed my grandmother so I happily agreed to go home. After I got here I found out.”

Eva’s mother broke the news by telephone. “She said, ‘Yaqi, you can’t go back to school in Guangdong because your dad has too many debts. We don’t have enough money to send both you and your brother to school.’ I was very sad. I cried and cried into the quilt.”

Eva must live in Pingshang in part because China’s school system has not kept pace with the country’s momentous population shift. Under the hukou, the household registration system that was established in the 1950s, people are still bound to their birthplace for access to education and healthcare.

The Chinese migrants who left their villages in the 1980s and 1990s left their children behind because the conditions in workers’ dormitories and their 12-hour shifts made it nearly impossible to raise a child. Later, more educated migrants found better jobs, rented private rooms and paid for their children to join them and attend unofficial schools. Today, more relaxed rules allow migrants to gain citizenship in one of the smaller cities if they can afford to buy property there.

By 2014, more than half of all children of migrants lived with at least one parent in a city, up from 30 per cent in 2010.

The logic of a migrant teenager’s education works like this: China’s highly competitive college entrance exam, the gaokao, can only be taken in the province where the student’s hukou is registered. The test requires memorising textbooks specific to that province, so students must attend high school and, usually, middle school, in that province. As a result, a migrant child’s path to the gaokao starts in the parents’ hometown, no matter how long ago they may have migrated away.

Migrant parents must choose between keeping their families together and their older children in school. The choice weighs most heavily on girls. Between the ages of six and 14, boys are more likely to join their parents in the city. Because of the cultural tradition of investing more resources in sons than in daughters, the girls who are left behind in the countryside head into their teenage years already at a disadvantage in China’s competitive education system.

Eva is one of the 61m left-behind children living in rural areas

Left-behind children, especially in the poorest villages, are more vulnerable to sexual abuse and kidnapping. Teenagers are far more likely to drop out of school or end up in jail. Sensational headlines about left-behind children killing themselves or others have shocked China, as have tales of tiny children left to take care of sick grandparents. Local governments will soon be required to provide guardians for the estimated 2m children who live without any adult present at all.

For better-off families like Eva’s, the toll is mostly psychological. “Most left-behind children maintain irregular and limited contact with their parents and feel lonely, isolated and deprived of support,” noted a 2014 Unicef report on Chinese children.

Eva’s nine-year-old brother was initially sent back to Pingshang too, but he misbehaved so much that Eva’s parents took him back to the city. As a little girl living with her grandmother, before she moved to the city, Eva felt jealous that her parents were raising her brother. Now that they are separated again, she misses teasing him.

Eva’s home in Pingshang is still half-finished, because her father ran out of money to build it. Ornate floor tiles contrast with raw concrete walls and a staircase without a banister.

Outside, frogs croak all night and roosters crow at dawn. Eva lives with her grandmother, an adult female cousin and the cousin’s two young sons, whose father is also away.

Eva squints because she doesn’t like to wear her glasses. The squinting makes her look anxious, and she is. When she lived with her parents in Guangdong, she worried that her grandmother might suffer a fall and that no one would take care of her. Now that she is back in Pingshang, she worries that perhaps she fought too much with her brother and caused her mother too much trouble.

The view from outside Eva’s school in Pingshang

Her father, Xie Zaisheng, worries about Eva too. He thinks living apart has hurt her self-esteem. “There’s no shame for me to talk about this, it’s a problem for our whole society,” he says. “This is the biggest weight on my heart.”

English was Eva’s father’s ticket out of Pingshang. “Dad was always very strict about me learning English,” Eva says. “He says it’s a way to become someone.”

At first, Eva hated the language: “Dad made me recite the ABCs and I got so mad, I almost ripped up the paper. My dad is very strict, so it was like a cold war at home. Then he sent me to a school in Guangdong called Little Oxford. They had two English teachers per class, one foreign, one Chinese. That’s where I fell in love with English.”

Eva talks about learning English at Little Oxford school in Guangdong

The implacable logic of the gaokao means that Eva would have had to move back to Pingshang for middle school even if her parents had been able to afford more private tuition in the city — their money problems only brought her exile forward by two years.

If Pingshang children do well in middle school (which they attend from age 12 to 15), they might win entrance to a boarding school in a nearby city. A better high school means a shot at a better college, which translates into a job with a city hukou. Children like Eva are sent back to the countryside to have a shot at a better future — in effect, to retrace their parents’ journey.

Thanks to his English, Eva’s father works as a quality control inspector in Guangdong, checking products for foreign buyers. Her mother, a middle school graduate, works at a supermarket. “If there’s something urgent, I call her,” Eva says. “But usually I don’t… I don’t want to bother her. Sometimes she works the evening shift and I don’t know what her schedule is.”

“They are so tired,” she adds. “I make them sad because I don’t behave.”

Eva’s mathematics teacher in Pingshang, Liu Zhenzhen, says Eva struggled when she moved from the city back to the school she had left as a small child. “She needed some time to adjust.”

Schools in Pingshang are good for a town of its size. The administration has not been shy about tapping the town’s diaspora for donations, to fill its budget gaps. A few years ago, a dance studio was built but it remains locked and unused. No dance teacher wanted to live in Pingshang.

The maths teacher rotates among classrooms of 50 children each, seated two-by-two at mismatched desks. The children chant the lesson, shouting out answers when she calls on them. At lunchtime, some lug buckets of food from the canteen back to the classrooms to eat. Others sweep the yard and mop the staircases.

When she grows up, Eva wants to be a teacher.

Eva in a classroom at her rural school

Nearly half of Pingshang’s adults have moved away, mostly to Guangdong. Manufacturing wages there are about 10 times average farming incomes at home. Xie Xiaolin, the head of Eva’s school, says about two-thirds of his 1,100 pupils have at least one parent away. Around one-third have neither parent at home.

He worries about road accidents and poor-quality street food as children make their way alone to school. In his experience, left-behind children tend to perform at the bottom of the class. “Their grades are not that good, and I feel their personalities are troubled,” he says. “First of all because they lack love. Secondly, they are isolated in school. They don’t communicate voluntarily, they are withdrawn.” Some children misbehave.

“It is a contradiction we can’t resolve,” he says. “Parents leave for the good of the child.”

School head Xie worries about the left-behind children attending his school

“The girls are easier to manage,” Eva’s maths teacher says. “The boys are naughty. If their parents aren’t around they tend to misbehave. Some of the girls talk to their grandparents or teachers, some don’t confide in anyone.”

Bad behaviour can work in a boy’s favour, as it did for Eva’s brother. Given the importance of a son in traditional Chinese families, parents are more likely to respond if a boy appears to be having trouble in school. Eva’s cousin, for example, left her office job in the prosperous city of Hangzhou and moved home after her son began skipping school.

It has been eight months since Eva left Little Oxford, and she is struggling to retain her English. Her new school doesn’t teach it. She has heard that her beloved foreign teacher, Emily, has moved back to the UK. She has found a new hobby, Honor of Kings, a fantasy role-playing game for smartphones that has taken China by storm.

It has also caused some storms at home. Eva’s father considers himself lucky to have escaped Pingshang just as China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation opened up a world of opportunity. He learnt English in night classes and by immersing himself in Hollywood movies. He wants Eva to study instead of playing video games.

A portrait of Eva’s deceased grandfather at home in Pingshang

“When we were back for Chinese new year, I discovered her confidence had slipped more than I had realised over the phone,” he says. “So I pushed her to study more — but she said she wasn’t as good as the other students.” The result was a screaming row that Xie now regrets: “I’m not a ‘tiger dad’,” he says, referring to the stereotype of a strict and demanding parent. “I want her to be optimistic and secure.”

Now that he has found decent work again, Xie says he is contemplating bringing Eva back to the city. Maybe, by the time she finishes high school, China’s policies will have changed so that she can apply to college from Guangdong, he muses. If not, maybe she can go abroad to study — but that is a gamble he is not sure he should take.

Eva and her older cousin cook dinner in Pingshang

At home before dinner, Eva sings a clear rendition of an English-language nursery rhyme that Emily taught her. Listening through a window, her cousin brushes away a tear and goes back to the cooking.

After I leave Pingshang, Eva finds another opportunity to practice her English: WeChat, the Chinese messaging app. “OK, sorry, I have a question,” she types. “Do you miss your children?”

Credits

US

Neil Munshi, reporting

Gaia Squarci, photography and video

China

Lucy Hornby, reporting

Giulia Marchi, photography and video

Additional reporting by Archie Zhang

Editing and Production

Edited by Cordelia Jenkins

Picture editing by Alan Knox

Graphics by Cleve Jones

Production by George Kyriakos

© THE FINANCIAL TIMES LTD 2017

All editorial content in this report is created by the FT. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded our reporting but had no prior sight of the content.