Politics is personnel, especially in China’s Communist party system.

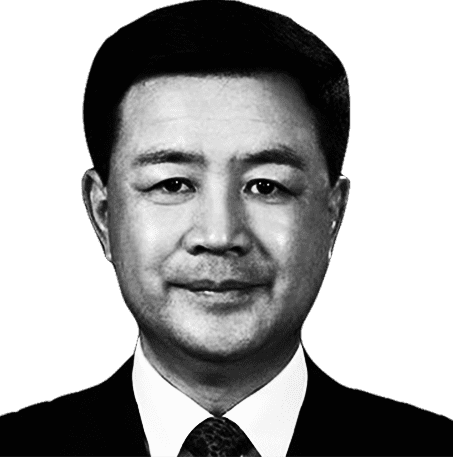

Xi Jinping, who is expected to be appointed for an unprecedented third term as leader, tightened his grip on power on Sunday as he addressed the party’s 20th congress in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

The most powerful ruler of China since Mao, Xi has centralised decision-making in his own hands in a way his recent predecessors could not have dreamt.

Since the early 1990s the Communist party has operated a series of term limits that kept the political peace between different factions. This has prevented rival groups, or one individual leader, from becoming too influential.

Xi has eliminated those restraints. He has achieved this by manipulating appointments to the upper echelons of the Chinese Communist party (CCP) and purging key rivals from the leadership.

It is through his control of the personnel system and a sweeping corruption crackdown that he has been able to bulldoze the factions that once dominated the party, stacking key positions with loyalists and sidelining any potential challengers to his leadership.