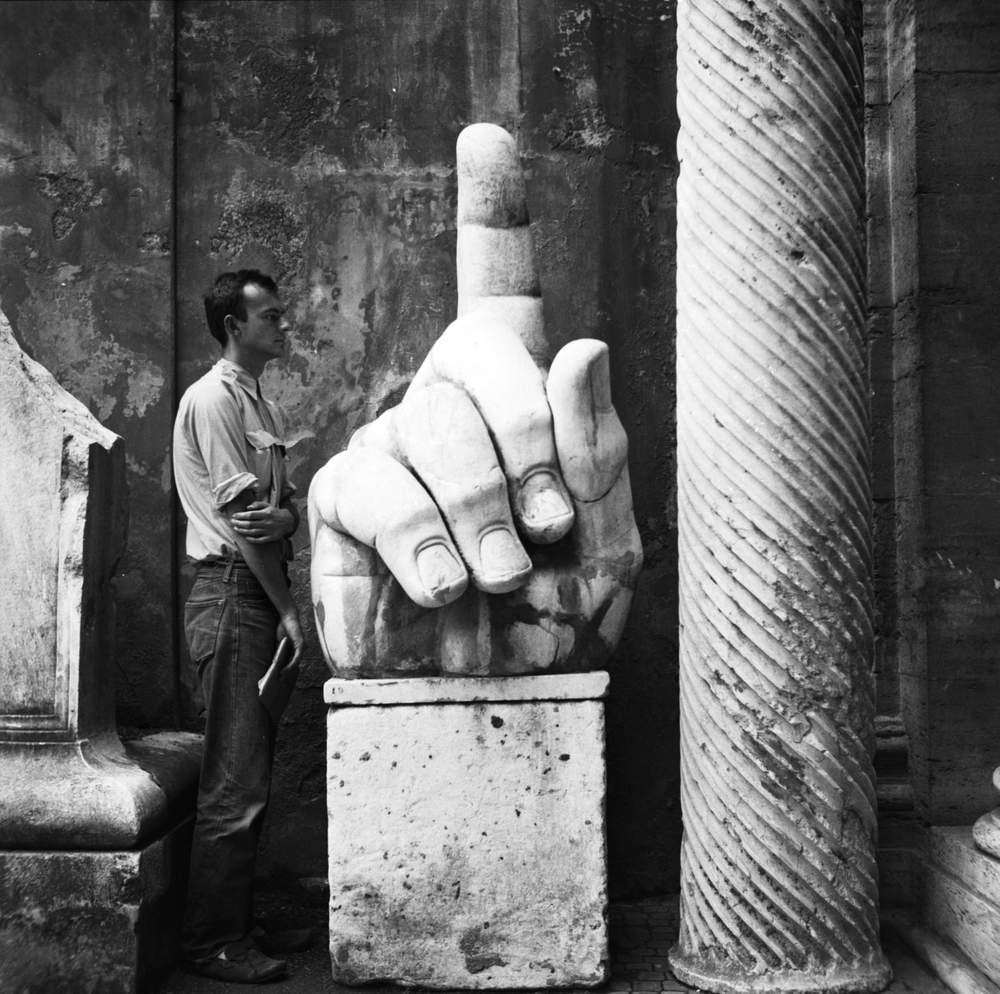

For SS17, fashion designers were pulled in all directions. Inspirations were broad: the joyous dynamism of girls on a beach by photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue, the red-booted potato diggers of 18th-century Ireland, or the still, silent grandeur of Hans Holbein’s portraits of Henry VIII all featured as reference points. But there were themes also, from the crazy swirls of psychedelia, to lush Tropicalia, to the quiet rigour of Brutalism, which lent the season a certain austerity.

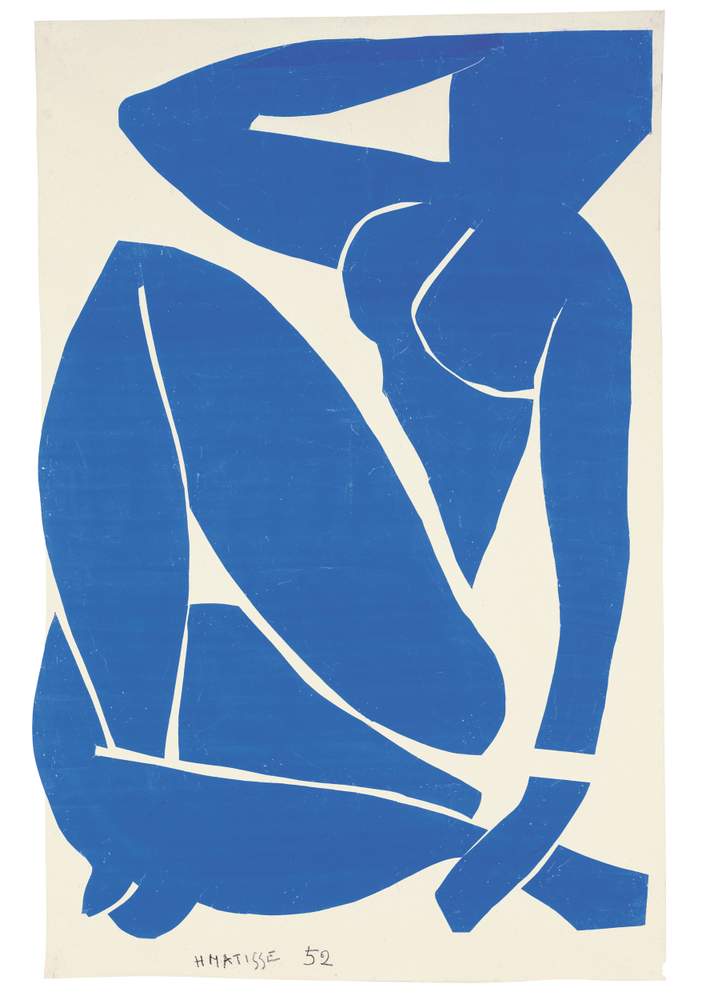

If any colour starred this season it was blue: at Hugo Boss, Jason Wu took the palette of David Hockney’s “A Bigger Splash” to create indigo girls spiked with viridian greens. At Joseph, the blues were abstracted and Matisse-like, while at Céline, Phoebe Philo took Yves Klein’s Anthropometry series to recreate the artist’s body prints on the canvas of a gown. The historian Simon Schama discusses our eternal fascination with this deepest of shades in Into the Blue.

Renée, Biarritz, August, 1930 by Jacques-Henri Lartigue ©Ministère de la Culture, France/AAJHL

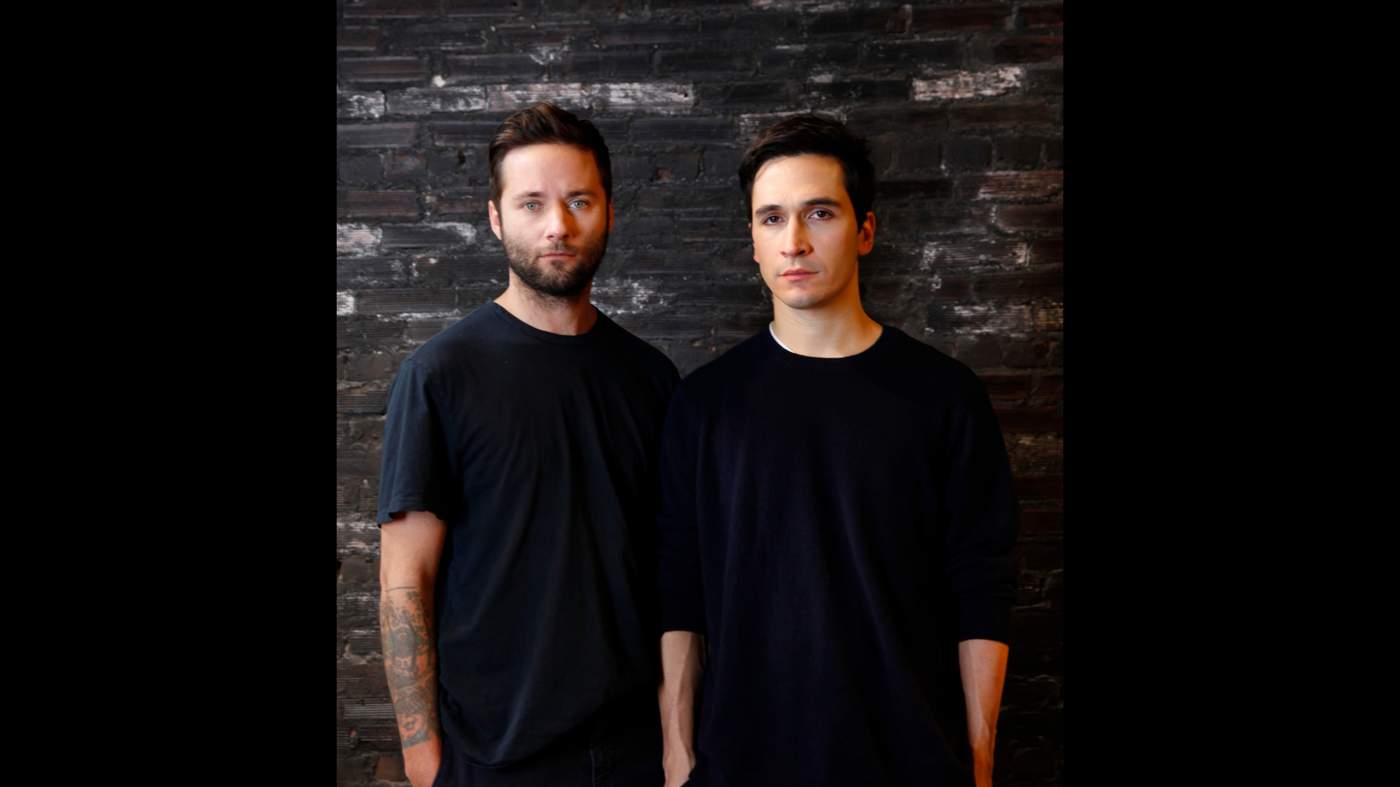

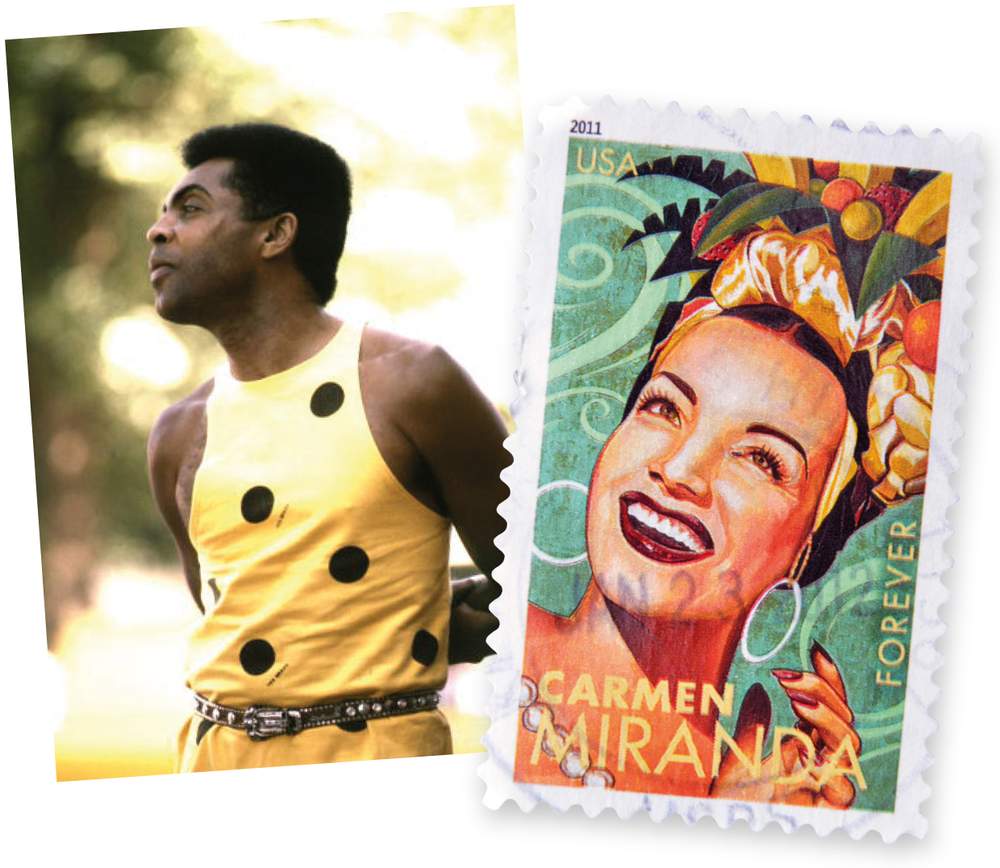

The catwalk was also a place of rediscovery. Both Akris and Proenza Schouler referenced the Cuban-born artist Carmen Herrera on their catwalks: the painter and sculptor who received her first solo exhibition at the Whitney last year, aged 101. The New York-based Proenza Schouler designers Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez have long taken art as a lead for their collections: in

‘It’s bad-ass and extreme’ they describe the works that have most inspired them.

The challenge of taking original artwork and making it both authentic in its execution and wearable is no easy one. For designer Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski at Hermès, however, the thousands of square, two-dimensional designs in the house’s scarf archives were too much temptation to leave alone. In Square Roots she describes how the scarfs’ unique geometries have inspired her work since 2014. Fashion’s rules are boundless, she argues, but sometimes the best things are kept within strict borders.

Jo Ellison, Fashion Editor, FT

For SS17, fashion designers were pulled in all directions. Inspirations were broad: the joyous dynamism of girls on a beach by photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue, the red-booted potato diggers of 18th-century Ireland, or the still, silent grandeur of Hans Holbein’s portraits of Henry VIII all featured as reference points. But there were themes also, from the crazy swirls of psychedelia, to lush Tropicalia, to the quiet rigour of Brutalism, which lent the season a certain austerity.

If any colour starred this season it was blue: at Hugo Boss, Jason Wu took the palette of David Hockney’s “A Bigger Splash” to create indigo girls spiked with viridian greens. At Joseph, the blues were abstracted and Matisse-like, while at Céline, Phoebe Philo took Yves Klein’s Anthropometry series to recreate the artist’s body prints on the canvas of a gown. The historian Simon Schama discusses our eternal fascination with this deepest of shades in Into the Blue.

Renée, Biarritz, August, 1930 by Jacques-Henri Lartigue ©Ministère de la Culture, France/AAJHL

The catwalk was also a place of rediscovery. Both Akris and Proenza Schouler referenced the Cuban-born artist Carmen Herrera on their catwalks: the painter and sculptor who received her first solo exhibition at the Whitney last year, aged 101. The New York-based Proenza Schouler designers Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez have long taken art as a lead for their collections: in

‘It’s bad-ass and extreme’, they describe the works that have most inspired them.

The challenge of taking original artwork and making it both authentic in its execution and wearable is no easy one. For designer Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski at Hermès, however, the thousands of square, two-dimensional designs in the house’s scarf archives were too much temptation to leave alone. In Square Roots she describes how the scarfs’ unique geometries have inspired her work since 2014. Fashion’s rules are boundless, she argues, but sometimes the best things are kept within strict borders.

Jo Ellison, Fashion Editor, FT

Simon Schama celebrates the colour that captivates on canvas and the catwalk alike

Except for the perverse poet Mallarmé who called on ashy fog to obscure the aggravatingly impassive azure, we all like a little cerulean in our lives: the sky above, the gentler kind of ocean below, limpid and warm. But do we want to wear it? I have a pair of sky-blue brogues, three words that don’t really belong in the same sentence, but they make walking like treading on air. I also have an Alexander McQueen boxy sky-blue jacket which may have been a mistake and a whole suit in the same colour from the crazy-great Boston store Alan Bilzerian. But if you want heavenly blue (which is what cerulean means, more or less) you’ll need to go to Amsterdam, to the Rijksmuseum, to the beddejak bed-jacket worn by the girl in Vermeer’s “Woman Reading a Letter”.

Woman Reading a Letter by Johannes Vermeer, c1663. Collection Rijksmuseum

One of the most sublime things the hand of man has made, Vermeer’s painting is bathed in a crystalline serenity which even screeds of literal-minded articles pondering whether the profile curve is a pregnancy or not, can’t spoil, not so long as you gaze at the radiant blue at the centre of the picture. Vermeer was prodigal with his ultramarine, the most expensive of all pigments. Most Dutch painters resorted to the much cheaper smalt, made from cobalt oxide. Over time smalt blue goes fugitive, fading to green, but it was all that artists like Jan van Goyen, dependent on high volume for his livelihood, could afford. But Vermeer was the opposite of a production line, painstakingly producing just 36 paintings over his career. The best of them concentrated maximum intensity of light and colour, and nothing delivered saturated radiance like ultramarine.

The pigment was costly because the lapis lazuli that was its base was originally obtainable only from Badakshan in what is now Afghanistan. In 1271 Marco Polo saw the mountain from which lapis was mined and marvelled at its beauty. The very term coined for the colour – “ultramarine” – beyond the seas – carried with it a charge of the magical-mythical so precious that it could only be used sparingly for sacred painting, in particular for the dress of the Virgin. The central panel of Duccio’s c1315 triptych in the National Gallery in London is a communion of the two sacred colours: ultramarine and gold. Fra Angelico applied it in economic patches. An apocryphal story had Michelangelo leaving his “The Entombment” unfinished for want of the expensive pigment. Conversely, slathering on the ultramarine was a coded boast: done exuberantly by Titian in the drapery of the wine god in “Bacchus and Ariadne”; excessively by the prolific 17th-century Roman painter Sassoferrato in Virgin after Virgin. It was a sign of Sassoferrato’s confidence that a self-portrait sets off his ostensibly modest black and white attire against a ground of spectacular cerulean.

‘Vermeer was prodigal with his ultramarine, the most expensive of all pigments’

The genius of Vermeer, in a culture which had removed religious images from its Protestant churches, was to transfer sacred luminosity to what were ostensibly domestic scenes – the pouring of milk; the reading of a letter – so that they became an intimate epiphany. Given the piety of Vermeer’s faith, it’s hard not to see the Dutch letter reader as a disguised Annunciation with the immaculate conception euphemised into the reception of the letter. Looking into the heart of the blue we are dwelling simultaneously in an earthy and a heavenly world.

This optical transport was scientifically planned. During a recent restoration the Rijksmuseum conservators discovered an undercoat of copper green above the primer and beneath the ultramarine, and it may be that extra layer which accounts for the sustained intensity of the colour. But the whole picture is a diffused rhapsody in blue: the leather backs of the chairs are blue (in all probability they would have been green); the rods holding the map of Holland and West Friesland (those parchment and flesh tones work optically with the blue as foil much like Duccio’s gold) are, in another departure from realism, a dark glowing blue. More important than any of these details is the filtered light itself which Vermeer has made into an ethereal veil of the utmost, pearly delicacy, so that the shadows of the chair backs and the ball-ends of the map rods fall in dark blue hues against the blonde wall.

Simon Schama celebrates the colour that captivates on canvas and the catwalk alike

Except for the perverse poet Mallarmé who called on ashy fog to obscure the aggravatingly impassive azure, we all like a little cerulean in our lives: the sky above, the gentler kind of ocean below, limpid and warm. But do we want to wear it? I have a pair of sky-blue brogues, three words that don’t really belong in the same sentence, but they make walking like treading on air. I also have an Alexander McQueen boxy sky-blue jacket which may have been a mistake and a whole suit in the same colour from the crazy-great Boston store Alan Bilzerian. But if you want heavenly blue (which is what cerulean means, more or less) you’ll need to go to Amsterdam, to the Rijksmuseum, to the beddejak bed-jacket worn by the girl in Vermeer’s “Woman Reading a Letter”.

One of the most sublime things the hand of man has made, Vermeer’s painting is bathed in a crystalline serenity which even screeds of literal-minded articles pondering whether the profile curve is a pregnancy or not, can’t spoil, not so long as you gaze at the radiant blue at the centre of the picture. Vermeer was prodigal with his ultramarine, the most expensive of all pigments. Most Dutch painters resorted to the much cheaper smalt, made from cobalt oxide. Over time smalt blue goes fugitive, fading to green, but it was all that artists like Jan van Goyen, dependent on high volume for his livelihood, could afford. But Vermeer was the opposite of a production line, painstakingly producing just 36 paintings over his career. The best of them concentrated maximum intensity of light and colour, and nothing delivered saturated radiance like ultramarine.

The pigment was costly because the lapis lazuli that was its base was originally obtainable only from Badakshan in what is now Afghanistan. In 1271 Marco Polo saw the mountain from which lapis was mined and marvelled at its beauty. The very term coined for the colour – “ultramarine” – beyond the seas – carried with it a charge of the magical-mythical so precious that it could only be used sparingly for sacred painting, in particular for the dress of the Virgin. The central panel of Duccio’s c1315 triptych in the National Gallery in London is a communion of the two sacred colours: ultramarine and gold. Fra Angelico applied it in economic patches. An apocryphal story had Michelangelo leaving his “The Entombment” unfinished for want of the expensive pigment. Conversely, slathering on the ultramarine was a coded boast: done exuberantly by Titian in the drapery of the wine god in “Bacchus and Ariadne”; excessively by the prolific 17th-century Roman painter Sassoferrato in Virgin after Virgin. It was a sign of Sassoferrato’s confidence that a self-portrait sets off his ostensibly modest black and white attire against a ground of spectacular cerulean.

‘Vermeer was prodigal with his ultramarine, the most expensive of all pigments’

The genius of Vermeer, in a culture which had removed religious images from its Protestant churches, was to transfer sacred luminosity to what were ostensibly domestic scenes – the pouring of milk; the reading of a letter – so that they became an intimate epiphany. Given the piety of Vermeer’s faith, it’s hard not to see the Dutch letter reader as a disguised Annunciation with the immaculate conception euphemised into the reception of the letter. Looking into the heart of the blue we are dwelling simultaneously in an earthy and a heavenly world.

This optical transport was scientifically planned. During a recent restoration the Rijksmuseum conservators discovered an undercoat of copper green above the primer and beneath the ultramarine, and it may be that extra layer which accounts for the sustained intensity of the colour. But the whole picture is a diffused rhapsody in blue: the leather backs of the chairs are blue (in all probability they would have been green); the rods holding the map of Holland and West Friesland (those parchment and flesh tones work optically with the blue as foil much like Duccio’s gold) are, in another departure from realism, a dark glowing blue. More important than any of these details is the filtered light itself which Vermeer has made into an ethereal veil of the utmost, pearly delicacy, so that the shadows of the chair backs and the ball-ends of the map rods fall in dark blue hues against the blonde wall.

There’s only one other being which manages the same degree of celestial-blue radiance, and that’s the Morpho butterfly. It has the same colour contrast of pale brown and brilliant cerulean as the Vermeer but deployed more functionally. The creamy-brown underside of the Morpho’s wings work as protective camouflage as it flits through the South American rainforest, feeding and mating. It has just 115 days to get this done but the odds of successful reproduction may actually be enhanced by the startling fact, discovered by Nipam Patel at UC Berkeley that many Morphos are gynandromorphs, with both male and female cell tissue present in their wings. But those wings are, by butterfly standards, enormous: 12cm wide; and when fully displayed by the male, are the flashiest bolt of colour in the forest.

Two Women at a Bar (oil on canvas) by Pablo Picasso, 1902. Artwork: ©Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2017. Photo: Bridgeman Images

After the invention of synthetic chemical pigments, starting in 1826 for ultramarine, but industrially produced later in the 19th century, blue-struck artists – Cézanne, Renoir, Picasso and, especially, Matisse could use variations of ultra and aquamarine lavishly. Cézanne could chill his blues, almost cruelly where, as costume or background they make the portraits of his wife inanimate. (It was not a happy marriage.) Or as in the Provençal skies over the Mont Sainte-Victoire he could make them tumid with heat.

Blue Nude III (gouache on paper) by Henri Matisse, 1952. Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France ©Succession H Matisse/DACS 2017

But the Morpho of modernism was Yves Klein for whom the perfect ultramarine came to serve as the be all and the end all of his work. For Klein (much taken with Zen) that peerlessly rich blue was the visualisation of impassive infinity, the colour which liquidated line, edge, space. In quantities that would have made Duccio and Vermeer faint, Klein produced work that were nothing but blocks of blue. There was a totalising madness about his quest for a hue that would exclude the slightest trace of the mineral impurities found in lapis lazuli. Klein bound the pigment in a synthetic resin he had specially commissioned and which he believed would retain the saturation of the colour in purer concentration than if it were suspended in any oil emulsion. When he had nailed it he patented the colour as International Klein Blue (IKB). In 1958 his fetishism extended to a controversial attempt to drown the obelisk on the Place de la Concorde in blue light; to creating IKB versions of Louvre icons like “The Winged Victory of Samothrace”; and to exhibiting the saturated (he liked to say impregnated) sponges as sculptures in their own right. The obsession made him a poster-boy for minimalist contempt for any kind of gestural art as well as figuration, the liberator of colour free from the presumptuous intervention of an artist’s hand.

‘For Yves Klein, that peerless blue was the visualisation of infinity’

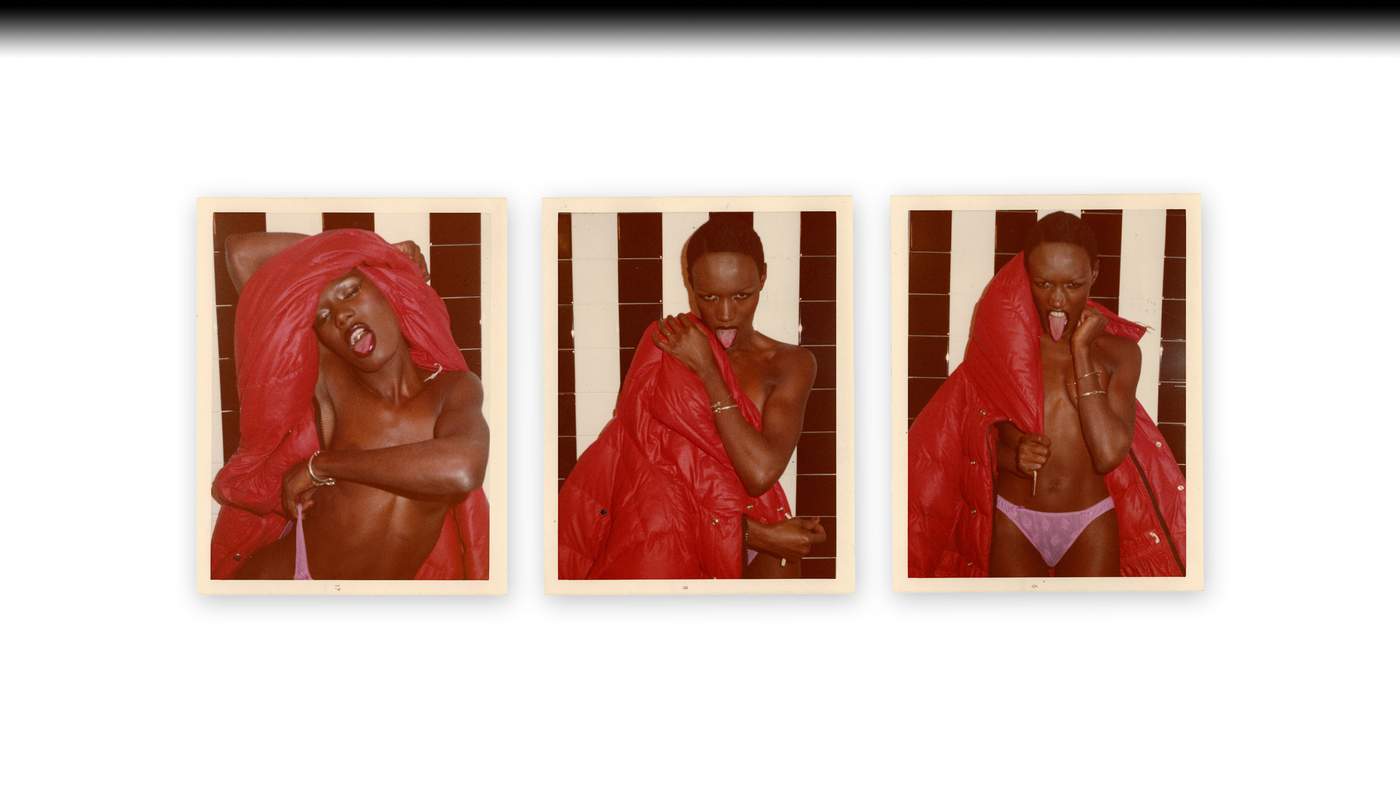

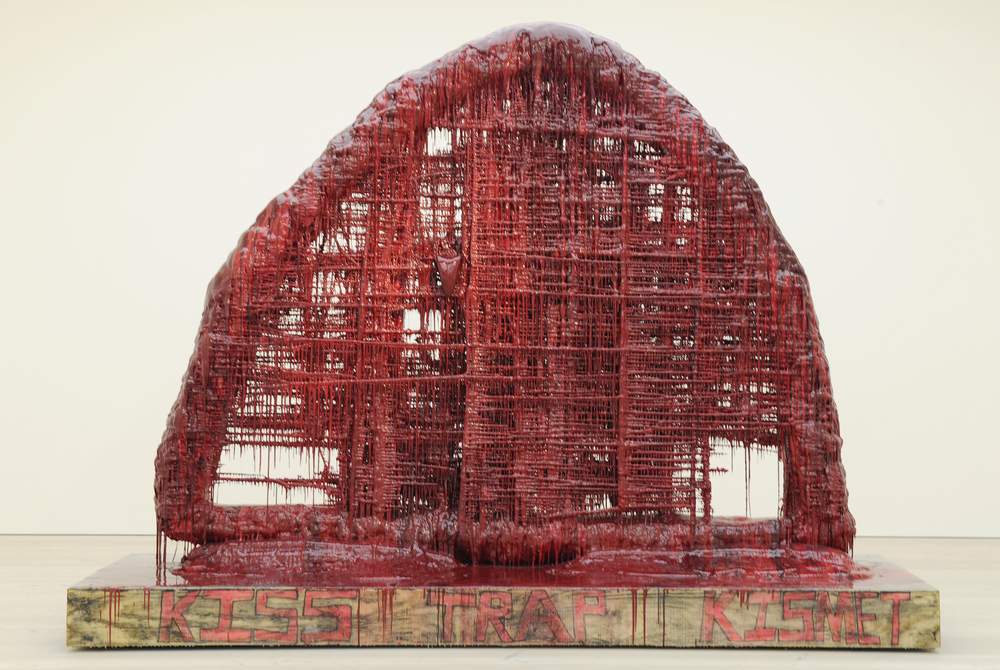

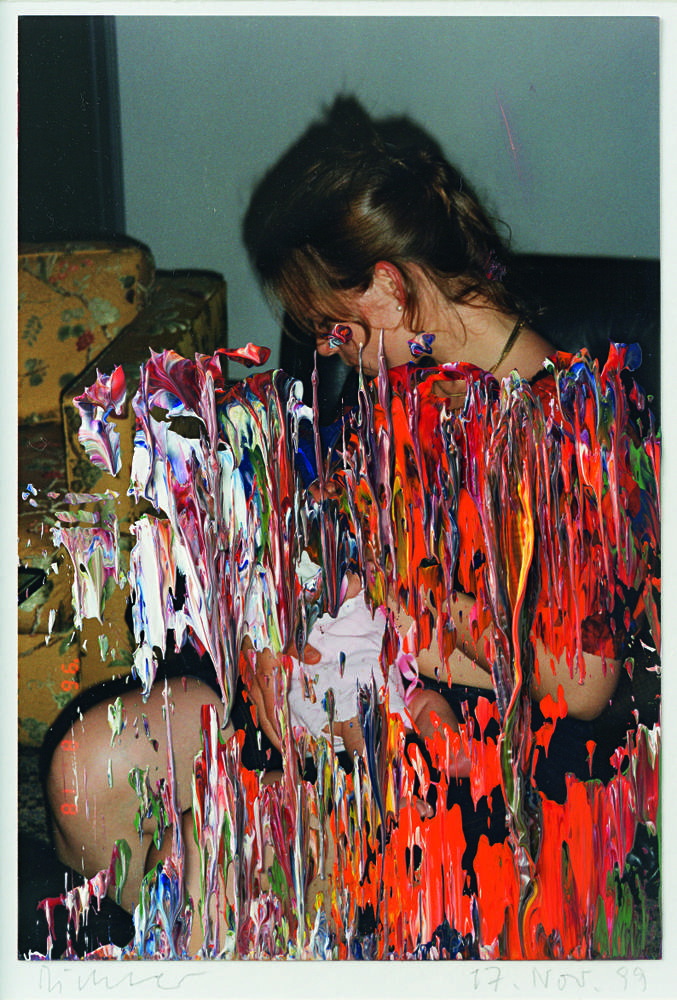

However tediously monomaniacal the serial Blues seem on the pages of catalogues and monographs, when you are in the actual presence of the work Klein made in the last few years before his fatal heart-attack at the age of 34 in 1962, the intensity of the paintings does deliver the retinal punch of its sensory force-field. Few of the paintings are, in fact, perfectly flat. Many of them are textured, pitted, studded and in some cases incorporate those sponges. The paintings that raised most eyebrows were done with what Klein called the “living paintbrushes” of naked female bodies, daubed in that same blue and then rolled over sheets of white paper. The best of them are actually very beautiful, flowing with a kind of balletic, exuberant vitality.

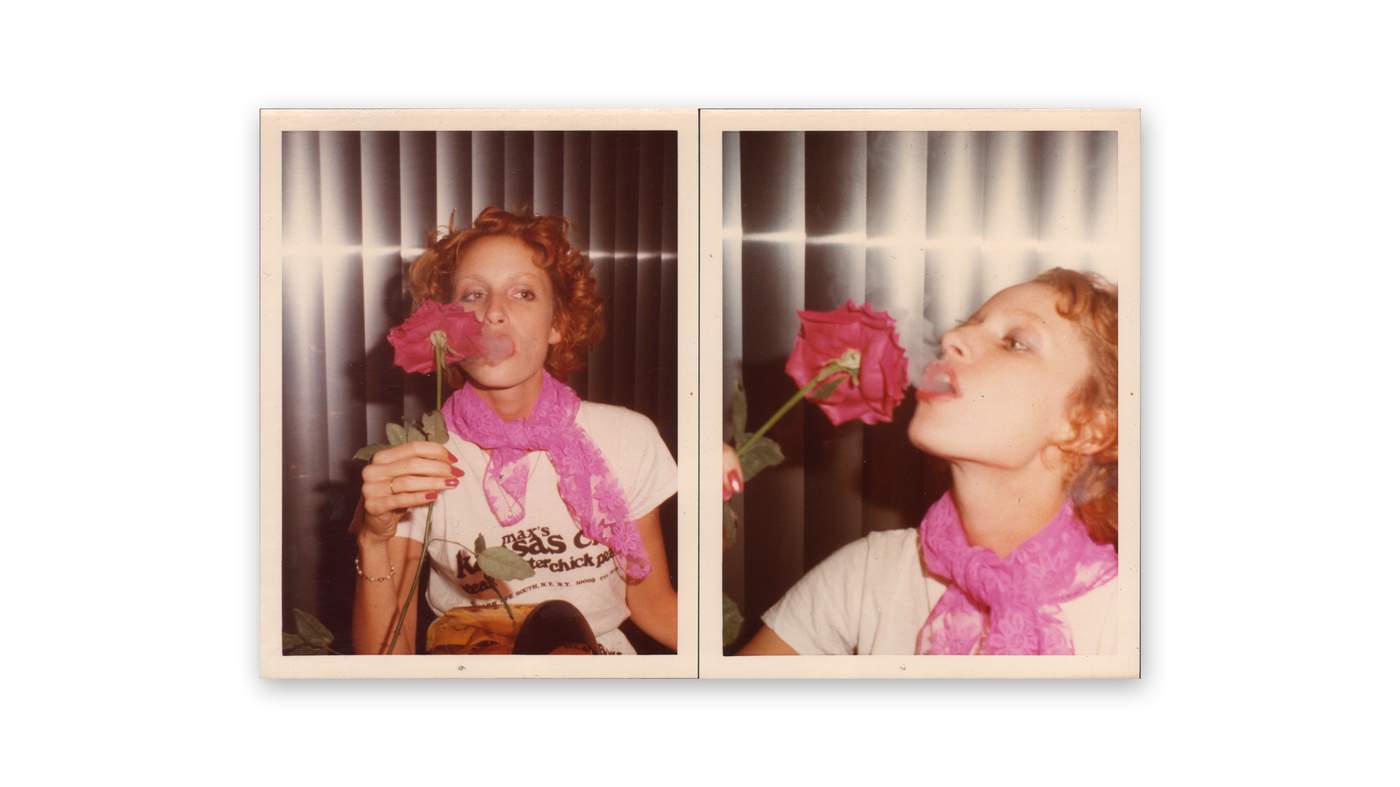

Yves Klein realizing an Anthropometry (ANT 15) in his studio at 14, rue Campagne-Première with his model Michèle, 1960, Paris. Artwork: ©Yves Klein, ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017. Photograph: Shunk-Kender ©J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2014.R.20)

Celine SS17

Blue can calm but, turning cold, blue can also kill. The calming hue can turn into the herald of mortality as blue stains appear on rosy flesh. It’s a bad sign when your lips go blue. And the colour is of course dense with sadness; the spectrum’s equivalent of the long sigh. As an expression of melancholy, “the blues” apparently came from the “blue devils” which, in 17th-century English, were said to possess those suffering from alcohol withdrawal.

But when the Blues are sung with that paradoxical union of joyful mournfulness – by Bessie Smith or Muddy Waters – they somehow make us happy. But if you want the all-time moody howl, there’s only one performance to have in your head while you’re hunting for blue suede shoes. That would be “Blue Moon”, sung, to the soft clip-clop of a cowboy’s horse, by Elvis: the only version of the song which drops Lorenz Hart’s unpersuasively golden ending.

The exhibition ‘Yves Klein’ is at Tate Liverpool until 5 March

There’s only one other being which manages the same degree of celestial-blue radiance, and that’s the Morpho butterfly. It has the same colour contrast of pale brown and brilliant cerulean as the Vermeer but deployed more functionally. The creamy-brown underside of the Morpho’s wings work as protective camouflage as it flits through the South American rainforest, feeding and mating. It has just 115 days to get this done but the odds of successful reproduction may actually be enhanced by the startling fact, discovered by Nipam Patel at UC Berkeley that many Morphos are gynandromorphs, with both male and female cell tissue present in their wings. But those wings are, by butterfly standards, enormous: 12cm wide; and when fully displayed by the male, are the flashiest bolt of colour in the forest.

Two Women at a Bar (oil on canvas) by Pablo Picasso, 1902. Artwork: ©Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2017. Photo: Bridgeman Images

After the invention of synthetic chemical pigments, starting in 1826 for ultramarine, but industrially produced later in the 19th century, blue-struck artists – Cézanne, Renoir, Picasso and, especially, Matisse could use variations of ultra and aquamarine lavishly. Cézanne could chill his blues, almost cruelly where, as costume or background they make the portraits of his wife inanimate. (It was not a happy marriage.) Or as in the Provençal skies over the Mont Sainte-Victoire he could make them tumid with heat.

Blue Nude III (gouache on paper) by Henri Matisse, 1952. Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France ©Succession H Matisse/DACS 2017

But the Morpho of modernism was Yves Klein for whom the perfect ultramarine came to serve as the be all and the end all of his work. For Klein (much taken with Zen) that peerlessly rich blue was the visualisation of impassive infinity, the colour which liquidated line, edge, space. In quantities that would have made Duccio and Vermeer faint, Klein produced work that were nothing but blocks of blue. There was a totalising madness about his quest for a hue that would exclude the slightest trace of the mineral impurities found in lapis lazuli. Klein bound the pigment in a synthetic resin he had specially commissioned and which he believed would retain the saturation of the colour in purer concentration than if it were suspended in any oil emulsion. When he had nailed it he patented the colour as International Klein Blue (IKB). In 1958 his fetishism extended to a controversial attempt to drown the obelisk on the Place de la Concorde in blue light; to creating IKB versions of Louvre icons like “The Winged Victory of Samothrace”; and to exhibiting the saturated (he liked to say impregnated) sponges as sculptures in their own right. The obsession made him a poster-boy for minimalist contempt for any kind of gestural art as well as figuration, the liberator of colour free from the presumptuous intervention of an artist’s hand.

‘For Yves Klein, that peerless blue was the visualisation of infinity’

However tediously monomaniacal the serial Blues seem on the pages of catalogues and monographs, when you are in the actual presence of the work Klein made in the last few years before his fatal heart-attack at the age of 34 in 1962, the intensity of the paintings does deliver the retinal punch of its sensory force-field. Few of the paintings are, in fact, perfectly flat. Many of them are textured, pitted, studded and in some cases incorporate those sponges. The paintings that raised most eyebrows were done with what Klein called the “living paintbrushes” of naked female bodies, daubed in that same blue and then rolled over sheets of white paper. The best of them are actually very beautiful, flowing with a kind of balletic, exuberant vitality.

Untitled Anthropometry, (ANT 76) 1960 by Yves Klein. ©Yves Klein, ADAGP, Paris / DACS, London, 2017

Blue can calm but, turning cold, blue can also kill. The calming hue can turn into the herald of mortality as blue stains appear on rosy flesh. It’s a bad sign when your lips go blue. And the colour is of course dense with sadness; the spectrum’s equivalent of the long sigh. As an expression of melancholy, “the blues” apparently came from the “blue devils” which, in 17th-century English, were said to possess those suffering from alcohol withdrawal.

Yves Klein realizing an Anthropometry (ANT 15) in his studio at 14, rue Campagne-Première with his model Michèle, 1960, Paris. Artwork: ©Yves Klein, ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017. Photograph: Shunk-Kender ©J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2014.R.20)

Celine SS17

But when the Blues are sung with that paradoxical union of joyful mournfulness – by Bessie Smith or Muddy Waters – they somehow make us happy. But if you want the all-time moody howl, there’s only one performance to have in your head while you’re hunting for blue suede shoes. That would be “Blue Moon”, sung, to the soft clip-clop of a cowboy’s horse, by Elvis: the only version of the song which drops Lorenz Hart’s unpersuasively golden ending.

The exhibition ‘Yves Klein’ is at Tate Liverpool until 5 March

Untitled Anthropometry, (ANT 76) 1960 by Yves Klein. ©Yves Klein, ADAGP, Paris / DACS, London 2017

Power sleeves and steely stares, the collections had commanding presence

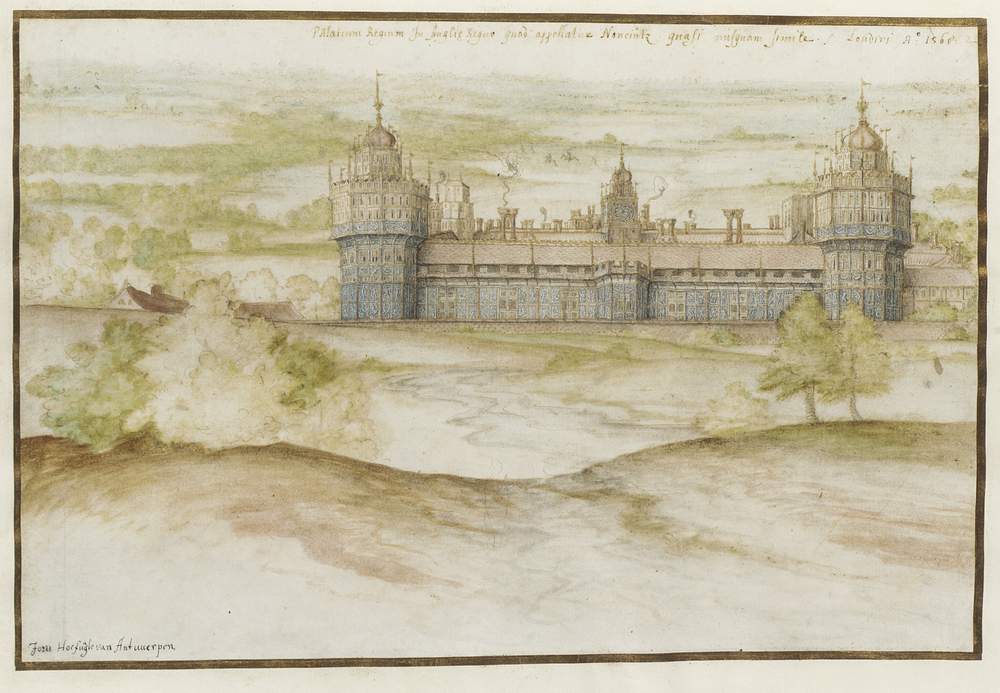

No surprise the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth lead many designers to re-examine that era’s dress codes. At JW Anderson, Hans Holbein’s famed depictions of that most alpha of English monarchs, Henry VIII, had inspired a wardrobe of leg-of-mutton sleeves, burlap day dresses and quilted corsetry. Described as “urban armour” for the modern working wardrobe, Jonathan Anderson wanted to work with “relics of aggressive masculinity”, and yet reinterpret them in a gentler, raw-edged way.

Victorian engraving of Henry VIII based on Hans Holbein’s 1537 portrait. ©Alamy

There were more Tudor moments at Marques’Almeida where elaborate ruffles and rich, colourful brocades recalled Elizabethan silks yet remained 21st century in sensibility. The sculptural bodices, bell-shaped sleeves and ankle-skimming breeches and boots also had a princeling charm. There were thigh-high boots at Balenciaga too, where designer Demna Gvasalia added a sheen of opulence to his spandex looks with archive jewelled embellishment and jersey silks. A bold Tudor shoulder featured frequently, ruffled, billowed and caped at Ellery, Simone Rocha and Céline. But nowhere was it quite so dramatic as at Comme des Garçons, where designer Rei Kawakubo’s study of “invisible clothing” found one model swathed in layers of ruffled red velvet. As wide as she was tall, she commanded attention, her presence as powerful as any Renaissance king. Jo Ellison

Nonsuch Palace from the South by Joris Hoefnagel, 1568 ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London

No frills: designers make a feature of fashion’s raw materials

Simple, clean tailoring with outsize features and, yes, lots of grey were a regular feature of the spring shows, where looks were reduced to an essential functionality on many of the catwalks. Presented almost in opposition to the sprauncier florals and patterns which appeared alongside, these were the pieces that added grit to so much girlie glamour. There were utilitarian separates at Hermès and Mulberry, where Johnny Coca used khaki work jackets and liquid leathers to punch up school-boy pinstripes, while practical all-in-ones tempered the more bohemian rhapsody at Isabel Marant.

Boston City Hall by Kallmann, McKinnell & Knowles, 1969. Photo: Ezra Stoller ©Esto, all rights reserved.

Designers eschewed accessories in favour of an outsize detail or silhouettes. The shoulder made a statement at Stella McCartney, while Marni’s cool separates were worn with pannier-style pocket bags. As with the architects whose raw design gained prominence in the 1950s, these designers took a similar interest in showing a garment’s construction; overstitching, button details and pockets took centre stage. There was volume too: shoulders were heightened or rounded to create a new architecture, while sleeves were pushed up to the elbow to convey a workmanlike attitude, or long and knuckle-sweeping with outsize cuffs. The mood was businesslike, no nonsense and tough. JE

The Brutalist Playground is at the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, Germany, until 16 April

How did a shipwrecked dress, a disco diva and a potato digger inspire the SS17 collections? Aimee Farrell finds out

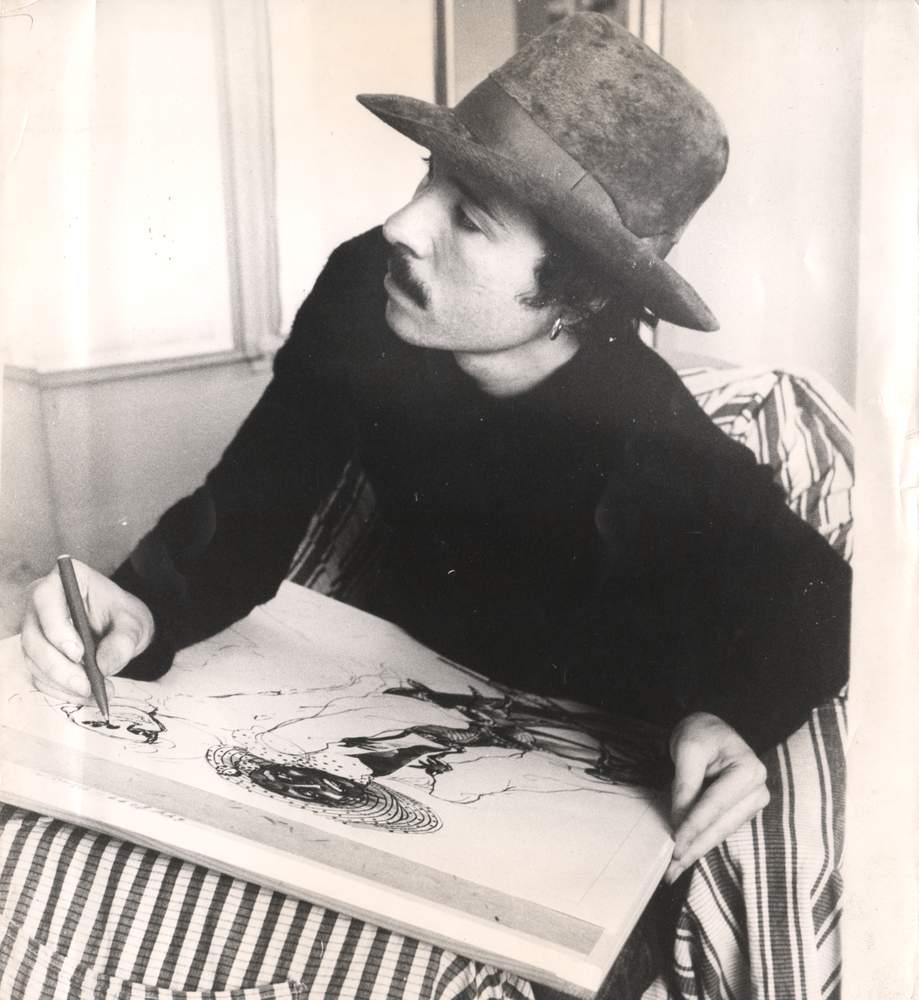

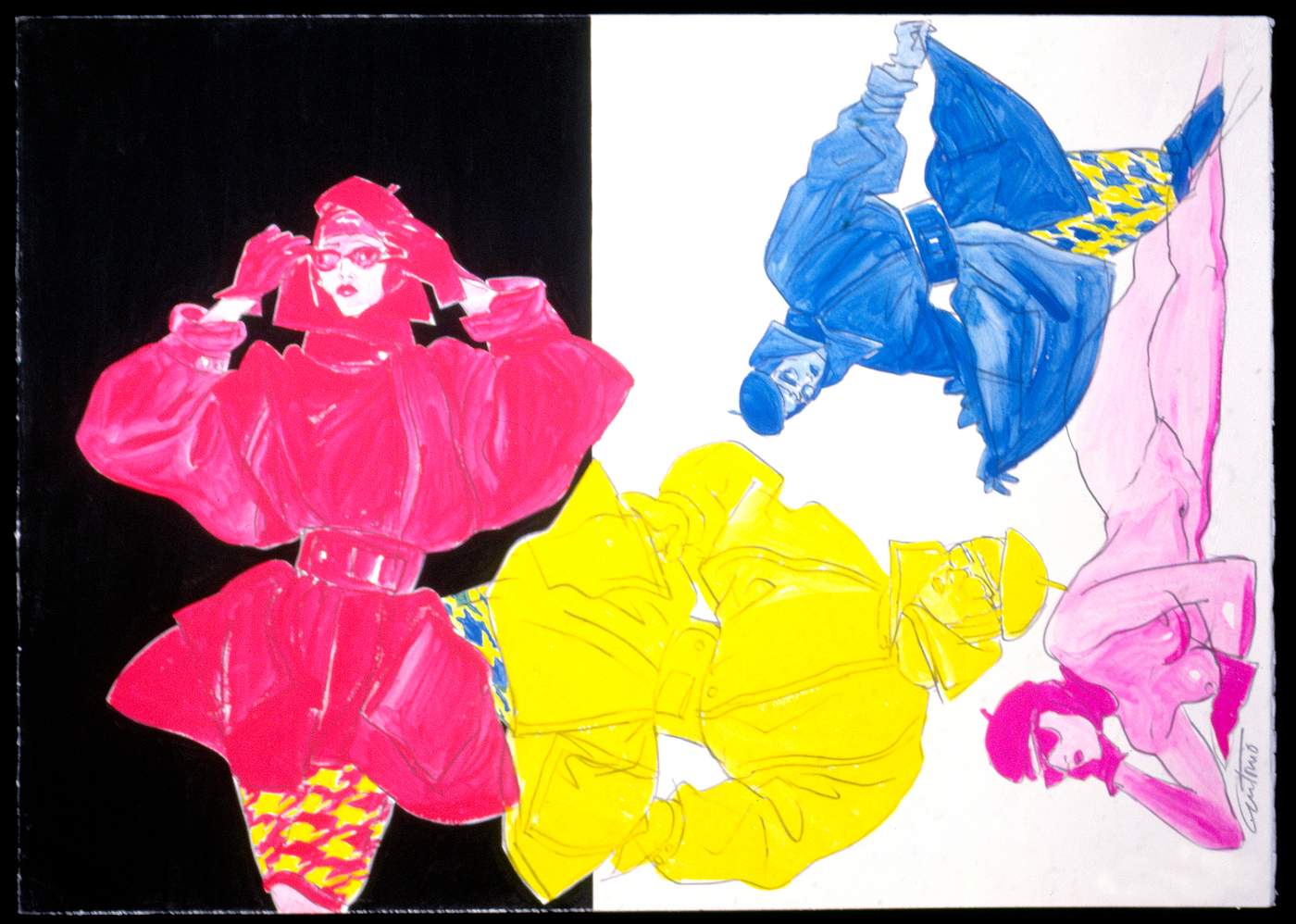

Sportmax Coats, pencil & watercolor, Milan, 1983 ©The Estate of Antonio Lopez & Juan Ramos

Bibi, Arlette and Irène. Storm in Cannes. Cannes, May 1929 by Jacques-Henri Lartigue ©Ministère de la Culture, France / AAJHL

Fashion gets groovy with whirling prints and acid-like abstractions

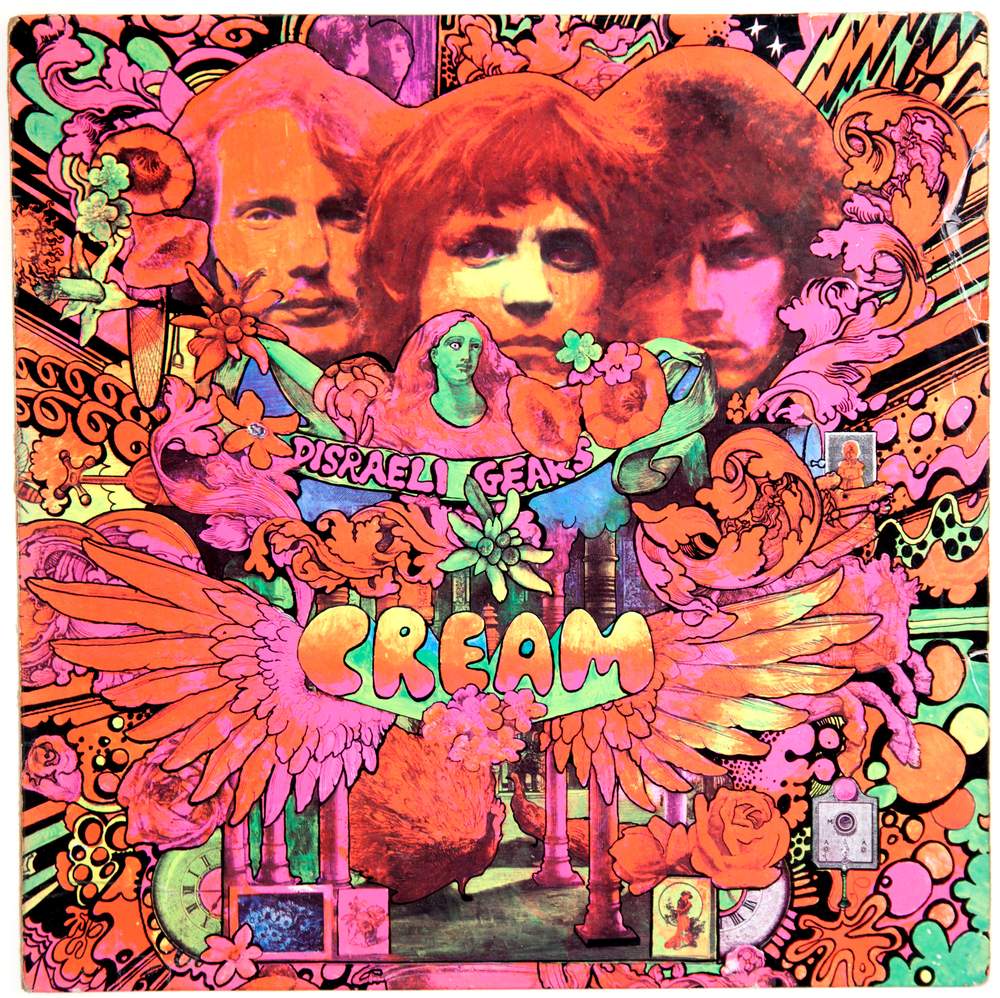

Maximalists rejoice! The rainbow colours and groovy attitude of psychedelia are back. And this season it’s part of a mash-up of influences that takes the 1960s and 1970s movement into new territory. Mary Katrantzou took ancient Greek motifs and patterns and “fused them with psychedelic art”; trippy optical squares on flared trousers, tunic dresses and skirts with peplums that mirrored the shape of ancient vases. At Louis Vuitton, Nicolas Ghesquière also offered an optical arrangement of chequered black and white which evoked the monochrome paintings of Bridget Riley. Flowing shapes, eclectic prints and hippy-style embroidery at Roberto Cavalli conjured up Woodstock so strongly you could almost smell the joss sticks.

Cream’s Disraeli Gears album cover, 1967 ©Alamy

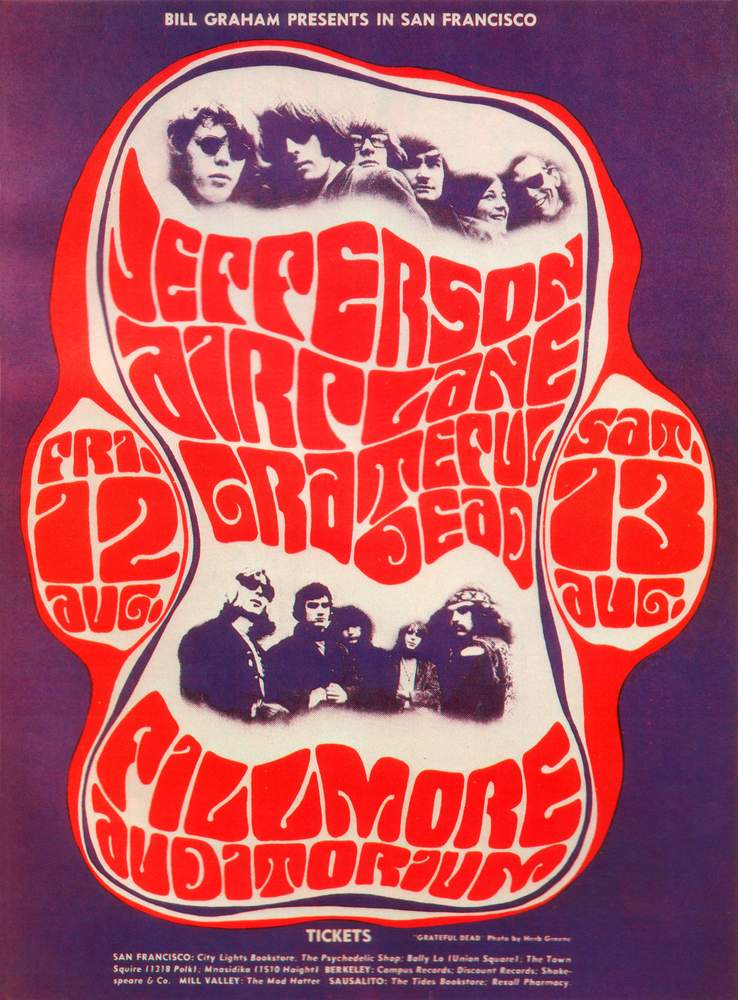

Fringing, skinny scarves and flares also owed a lot to psychedelic rock star Jimi Hendrix, while the palette echoed the clashing block colourways of that era’s poster art. Hendrix was also a major influence on designer Chitose Abe, creative director at Sacai, who summoned Hendrix’s personal style as one of her “game changers”. Youth culture was at play too at Marc Jacobs, whose club-kid models were inspired by raves, acid house, anime, Harajuku girls, Boy George (hence those controversial colourful dreadlocks) and 1980s London. Stomping down the catwalk to rave classic “Born Slippy”, models wore jackets and towering platform boots decorated with hallucinatory illustrations by artist Julie Verhoeven. Taps, cacti, rainbows, snakeskin, mouths, lemons and ovens all mingled together in her kooky cartoonish designs. Far out. Carola Long

Poster for 1967 Fillmore auditorium concert ©Lebrecht Music and Arts Photo Library / Alamy

For Proenza Schouler’s Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez art is essential to their work. They talk about the people whose palette, passion and creative process inspire them

How do you use art in design?

Jack McCollough It changes every season. Sometimes it’s texture, sometimes it’s palette. Sometimes it’s just the artist’s process and how they work that inspires us. We never like it to feel like a direct reference. Fashion can feel a bit recycled, so we try to look beyond that and get different ideas from all over the place.

Why does art inform so much of your work?

Lazaro Hernandez We started our company right out of school, we don’t have the 100 years of fashion to pull from our archives. Proenza Schouler isn’t this heritage brand. We’re just pulling ideas and images from our lives and making it up from scratch. JM American modernism is something we’re really drawn to. I guess we’re in a fashion dialogue at any moment. What’s happening. What’s our stance on this thing that’s happening right now? Are we going to go in that direction or not? And sometimes we reject what’s happening and we go the opposite direction.

What are you drawn to currently?

JM I think aesthetically, we’re in a new phase. We used to sketch the collections at the very beginning of the season, and our sketches were exactly how the show would look. Now the show will be completely different. LH I think we’re more confident and therefore we’re freer and looser with things. We’re not being too rigid. The SS17 show was a good example: we used a bunch of different references and approached it more as a curatorial project than as a fashion collection. Mixing all these references into one big pot and seeing what came out. The whole thing had movement and more life and energy to it.

Have you ever bought the art you work with?

LH We definitely try to collect what we can, and where we can afford it. The Robert Rymans and the Cy Twomblys are a little… expensive for us.

Do you think fashion is art?

JM We think fashion is design. I think art has a spiritual quality. Art has the quality of just being an object and a thing that exists that fashion doesn’t have. I think good fashion has to work on many levels, but at the end of the day it’s a product. It has to be bought and sold and produced. And it has to have a function. It’s not enough to create clothing just to sit on a mannequin in a museum. We like to think the clothing we make has to have a life after we present it on the runway. It’s for women to use and wear and own. I think that functional aspect makes it not art. It can be art-like but we would never say that we’re artists in any way. We have too much respect for real artists to say that.

The catwalks bloomed with lush florals and a Latin American beat

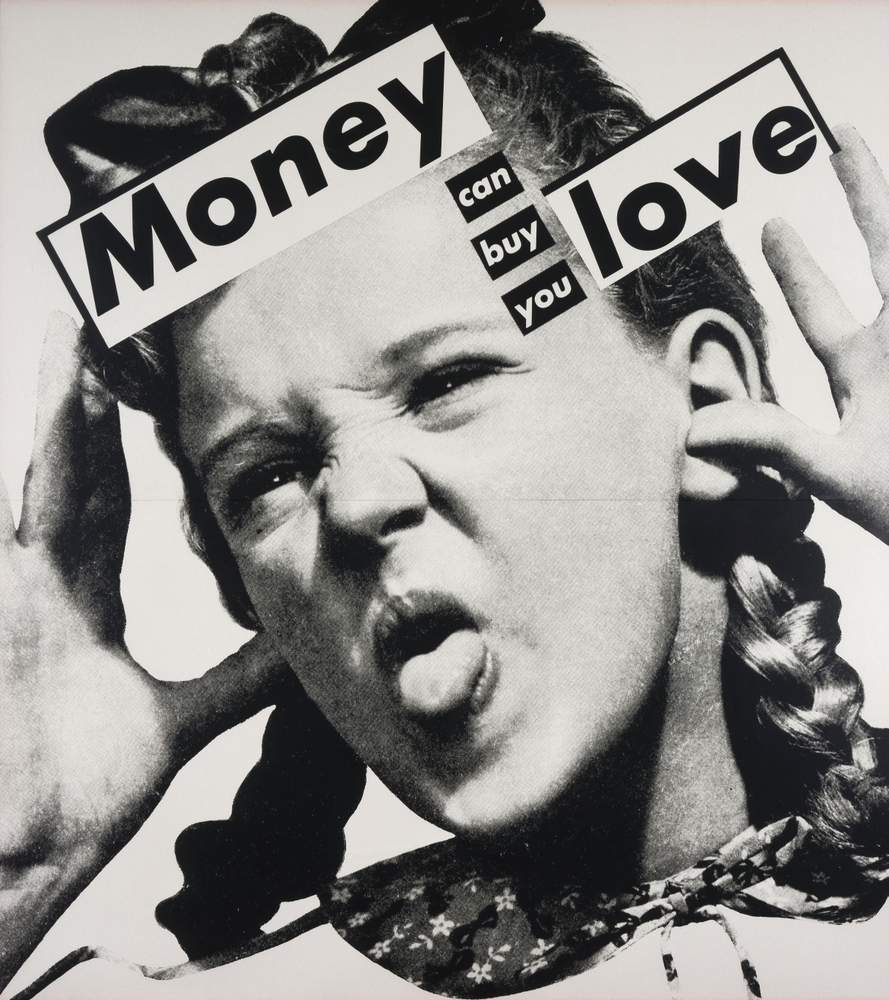

Feminism! Love! Futuresex! For SS17, designers said it with a slogan

At Hermès, designer Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski has taken the house scarf to new dimensions. By Jo Ellison

A big square, typically measuring 90cm-by-90cm, and designed in infinite variety, the carrè (or scarf) has become as powerful an emblem of Hermès as the saddlery on which the French luxury house was founded in 1837 – and far, far prettier to behold. Serving as a canvas for infinite interpretations, the first scarf design was a simple block-print conceived in 1937 by Robert Dumas, one of the Hermès-family heirs. Today the house boasts an archive of more then 2,000 scarf designs, to which a stable of some 50 freelancers contribute further designs each year.

For the house’s current womenswear designer, Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski, the scarf has become an intrinsic part of her design. Since taking the creative reigns in 2014, the French-born designer has used the scarf in myriad ways, incorporating prints into her ready-to-wear collections and pushing the technical capabilities of the studio in her quest to reinvent it.

“There’s a very strong heritage feeling with the scarf,” she explains from her design studio in Paris. “It’s about the equestrian world. It’s about travelling. It’s about the dream. It’s about so many different things. When I arrived at Hermès, I was fascinated by what could be revealed when you work on the colours of a classic scarf, but also how you could show things you might not see when you wrap it around your neck. I wanted to push it to another level.”

Vanhee-Cybulski’s fascination plays out in many ways. “I like to play with the different proportions and cuts,” she says. As well as creating separates tailored from the scarf’s precise proportions, she has spliced it to create knife-edged pleats, and punched its designs into leather. She loves the scarf because, while tailoring requires a strict adherence to “the architecture of a garment’s construction”, a scarf, “you just drape, so it’s much more pure”.

One thing she won’t do, however, is cheat. “I always use the exact dimensions of the scarf, whether it’s the 70cm, 90cm or giant 140cm squares. I try to stay purist because we work with screenprint factories and a specific frame. And if you have a perimeter that you can’t overcome, it’s interesting… within that perimeter, you find your freedom of creativity.” But does she have favourites? Of course she does…

Brides de Gala by Hugo Grygkar, 1957

One of the house’s most distinctive scarfs, by the designer of the first Hermès carrè, Hugo Grygkar, with input from Robert Dumas, the “Brides” has adorned the heads of both Queen Elizabeth II and Sophia Loren. “It’s a very interesting scarf because it represents two things for me: an extreme minimalism, and a deep femininity,” says Vanhee-Cybulski who has returned to it several times in her studio. “I wanted to liberate it for a contemporary woman. And I love the idea of taking something that belongs more to a certain type of pop culture and mixing it with a very intricate drawing of the saddle.” The scarf also offers a specific challenge. “Because an illustration is one dimensional, I have to erect a volume and a dimension for it to be worn on the body so the colours and the composition are really important. That’s always interesting.”

Eperon d’Or by Henri d’Origny, 1974

Conceived by Henri d’Origny, one of the most illustrious of the Hermès scarf designers who has spent 55 years working with the Maison des Carrès, this bandana scarf has been a key code of Vanhee-Cybulski’s collections. She is especially drawn to its kaleidoscopic quality. “I always fall back on d’Origny’s scarves as a source of ideas and inspirations,” she says. “He’s an extraordinary illustrator, but this idea of symmetry is innate in him: he can really draw within a square which is not an easy thing to do.” Despite their vintage, the Eperon, like the Brides de Gala suggests a certain modernity to the designer also. “I’m a big fan of the artists Josef Albers and Dan Flavin,” she continues “and when I see the Henri d’Origny I feel that same sense of composition. It’s unique. Within that square he manages to create all these intricacies and designs and twist them into something dynamic. Then, when you drape or tailor it, it allows you to unknot another dimension. He’s a great mental gymnast.”

Indigo Eperon d’Or bandana silk twill print man’s shirt and skirt with inverted pleats, Hermès AW15

For her debut collection, AW15, Vanhee-Cybulski used the scarf to create a bold print shirt and panelled skirt constructed from perfectly proportioned pieces. “I wanted to look at a new androgyny,” she says of the sporty day collection which also featured leather overalls and quilted equestrian jackets. “This was a confident men’s shirt made in twilled silk. I liked the tension, and that this look was a dialogue between something masculine and something extremely feminine. I think also, it was about injecting my story into the house, to study the scarf or motifs that are the DNA of Hermès and see how I could translate them in a more specific way.”

Le Jardin de la Maharani by Anna Faivre, 2016

“I love the idea of paisley,” says Vanhee-Cybulski. “It come from a very classic tradition and it was something I really wanted to translate into a garment.” Developed and used for a small capsule collection last year, Vanhee-Cybulski took the Maharani and its paisley design and used it in every way. She found its most delicate expression, however, in a pastel paisley perforated leather. The technical specificity of the task was painstaking. “You have to work on perspective, so we chose to translate the drawing with three different diameters – small holes, medium holes, bigger ones. It was a very long project. Also, we placed the pattern as though draped, like you would a silk scarf; everything had to be absolutely calibrated so that it could be framed within the little leather pieces because, how do you translate a 90cm-square into leather skins which are a bit smaller?” With immense patience, it transpires.

Passementerie by Françoise Heron, 1960

Anyone can submit a scarf design to Hermès. The house currently works with around 50 freelancers worldwide, including Kermit Oliver, a former postman who lives in Waco, Texas, who has designed 16 carrès. Françoise Heron, whose Passementerie scarf inspired the house’s latest resort collection, is known for richly feminine designs but always leaving her scarfs unsigned. “The Studio Dessin is an amazing database because we work with so many different illustrators,” says Vanhee-Cybulski. “We have our classics and then sometimes we make a discovery, so it’s very dynamic.” Moreover, it’s constantly evolving. “It’s extending the know-how and the sensibility of the house but also the sensibility of the illustrators,” says the designer. “It’s a great place of dialogue.”

Dress, in silk marocain crêpe, flat screen-printed with a design inspired by the Passementerie scarf, and sneakers, in woven silk with Cavalcadour print, Hermès Resort 2017

Eperon d’Or by Henri d’Origny, 1974

Vanhee-Cybulski used the Eperon d’Or in the SS16 collection, this time making a feature of its bold blue trim. This was a “contemplative” design, says Vanhee-Cybulski. “The more you look at the scarf, the more you understand the different shades and perspectives, and the more you observe, the more you connect the dots. The blue lines frame the square. They’re very loud; they’re really shouting out to help you understand the outlines of the garment, but when you look inside, you just see all these different weaves that give you an idea of different volumes and shades.”

Sailor dress in the ivory white Eperon d’Or silk jacquard, Hermès SS16

Vanhee-Cybulski enjoys the rigour of a scarf’s geometry. “Whether you are a fashion designer or a car designer, there are rules or certain ways of doing things. I think it’s interesting to understand how it works so that you can choose to go along with it, or not. It’s always a statement of choice.”

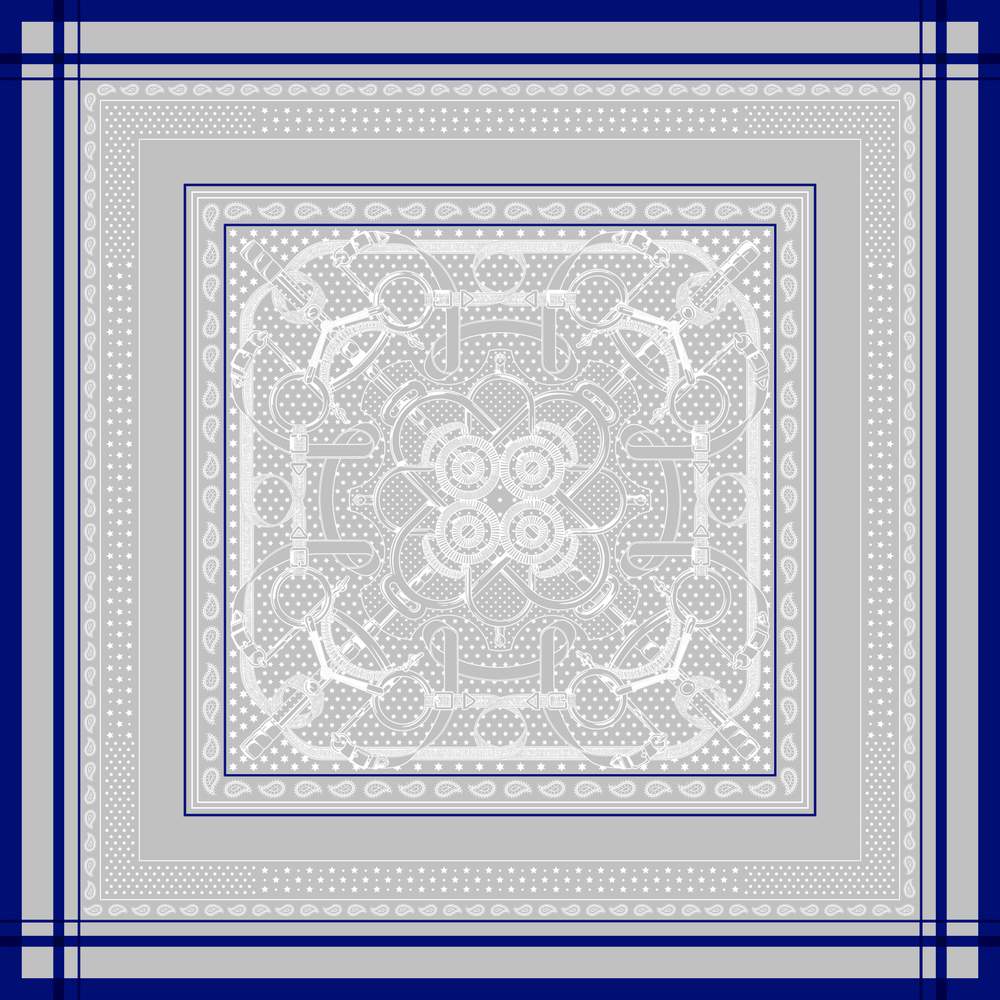

Cavalcadour by Henri d’Origny, 1982

For SS17, Vanhee-Cybulski took a classic scarf design of belts and horse bits by d’Origny and used its distinctive lines on prints and embroideries. The art was in the subtlety of its use. “If you look closely, the Cavalcadour was everywhere,” she says. It was there on the skirts, folded into knife-edge pleats interspersed with the “Fantôme” version (below) of the Cavalcadour that rendered it in simple monochrome. It was used also as the subtlest of embroideries on crisp white cotton shirts and khaki shirt dresses, “where all the stitches were representative of the scarf’s design” says the designer. And it was printed, like a ghost pattern, on acid yellow silk. Like the most beguiling of optical illusions, the Cavalcadour only revealed itself to those who were searching for it. Says Vanhee-Cybulski: “I just wanted to give the scarf a whole new dimension.”

Silk and polyester pleated knit wraparound skirt printed with the Cavalcadour Fantôme motif, Hermès SS17