Audrey Hepburn having Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Johannes Vermeer’s wan-faced Girl with a Pearl Earring, F Scott Fitzgerald’s jazz-age novella The Diamond as Big as the Ritz: art has a fast reputation for plundering the jewel box. And why not? What could be more evocative or enticing than a gobstopper-sized gemstone – especially when found on an exotic neck.

Repossi Elliptiques ear cuff in black gold with diamonds © Juergen Teller

Jewellery is the star of the Art of Fashion’s third issue – a tribute to the Croisette at Cannes, where film and fine jewellery are once again coming together at the most glamorous of film festivals, and the artisans and craftsmen who make them. Writer Chloe Fox explores the magical power of the pearl, nature’s most alluring mystery, while Vivienne Becker takes the tiara on a cultural trip, from the court of Empress Joséphine deep into the Forbidden City.

Jewellers, an exotic breed of their own, occupy a vaulted position in the luxury world, a realm where expense and execution are only hampered by the limits of their own creativity. But what inspires them? Victoire de Castellane, Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana and Gaia Repossi all talk about works that have sparked their dazzling creations. Shiny happy people? You bet they are.

Jo Ellison, Fashion Editor, FT

Jo Ellison enters the sparkly, bejewelled and very mischievous mind of Dior’s creative director

Victoire de Castellane, the creative director of fine jewellery at Dior since 1998, and designer of her own eponymous line, first started playing make-believe with her mother’s jewellery in infancy and has never stopped since. A shy little girl, whose aristocratic parents’ divorce cast a sad shadow over her childhood, she learnt early on that her dream life was infinitely more exciting than the lonely interior of the playroom. “I was obsessed with having my own universe,” says the designer. “So I decided very, very early on to jump into the world of my own imagination.”

Today, de Castellane is in her studio, a pale grey apartment near Dior’s headquarters on avenue Montaigne in her home town of Paris. She is surrounded by shelves of art books, boards of references and pots of felt pens. The pens are a familiar feature of her artist kit: the tools she uses to depict herself – a long black silhouette with heavy blonde fringe – alongside Monsieur Dior, in sparkly animations in which the two voyage time and space on bejewelled adventures.

De Castellane’s jewels are an especially pretty study in escapism, and she puts play before all other preparation when it comes to work. Her design owes much to the rich screen world she fell in love with, in particular the lush Technicolor of musicals like An American in Paris and Mary Poppins. “I was obsessed with Hollywood, all the Gene Kelly movies, Liza Minnelli, Marilyn Monroe,” she says of her cinematic inspirations.

Still from Disney’s 1964 ‘Mary Poppins’ the concept work for which was created by Mary Blair © Entertainment Pictures/Alamy

One of her early heroines was Mary Blair, the artist who rose to prominence at Disney during the 1940s and created the concept work for Alice in Wonderland, Cinderella and Peter Pan. “I’m crazy about her work,” says de Castellane. “She really created the atmospheres and worlds in which these characters would become immersed. I still want to enter her worlds.”

De Castellane still adores a fairytale, but now prefers to tell her stories with gemstones and precious metals. And while she takes inspirations from diverse subjects – a dancer’s ribbons, an artwork, the line of a chair leg – her ultra-feminine designs are guided by the same primal emotions she got from her cinematic favourites.

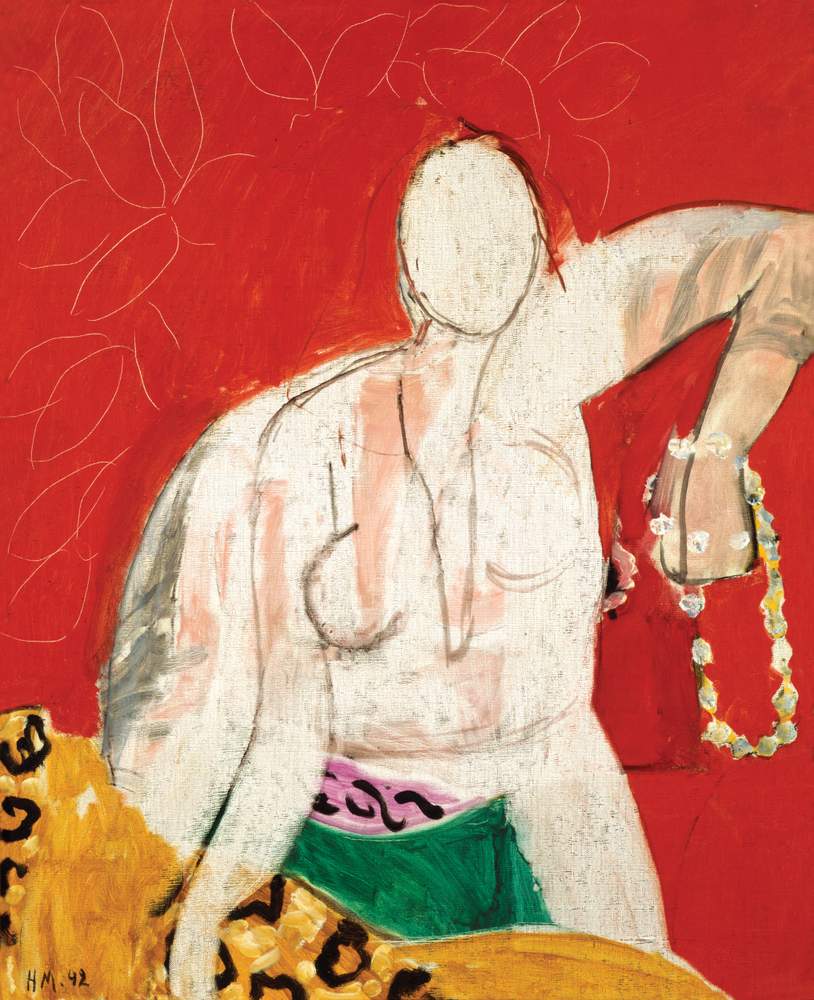

“I take the energy of the good things – the shapes of nature, colours, a painting – as my inspirations,” she says. “It’s not calculated. It’s very spontaneous. I always have a shock when I see a Matisse, for example, because the colours have such a powerful effect on me. They make me feel so happy. Animals make me happy too. I love monkeys. And I love lions, tigers, leopards – all the big cats. And dogs. They make me understand why it’s so good to be alive. For me, it’s very important to find this joie de vivre in my work, and to try and give it.”

She admires Picasso because his work epitomises the child-like attitude she tries to find in the studio. “That’s why it’s so charming because it’s absolutely free,” she says of Picasso’s animal sketches, mere strokes of ink that suggest each creature’s contours.

Likewise, her Dior collections are a girlish mash-up of ideas and inspirations. “I hate to work in a school way,” she says. “I like to have fun working with a subject that’s very classical.” For last year’s Versailles collection, she began with the palace’s interiors, the Louis Quatorze chairs and sumptuous gilt furniture, and then threw in other evocative details. “I didn’t want to do something very first degree,” she says, “so I worked with the idea of the 17th, 18th, 19th centuries and the evolution of jewellery in one piece. It was a little chaotic.”

The Pink Studio, 1911 (oil on canvas) by Henri Matisse (1869-1954) Photo: Bridgeman Images © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2017

The final pieces included black silver, oxidised silver and pink gold settings, with stones cut to represent the different eras. But the mood of the collection was romantic. “An atmosphere can be the start of the inspiration. I can start with a world,” she says. For the Versailles collection, that world was candlelit.

“I think of that scene in Stanley Kubrick’s film Barry Lyndon where everyone is cast in that special colour, that glow,” she continues. “It’s absolutely beautiful. So when I designed this collection I was thinking of the way a woman might be wearing jewellery at night, and that special glittering light that make-up can’t touch.”

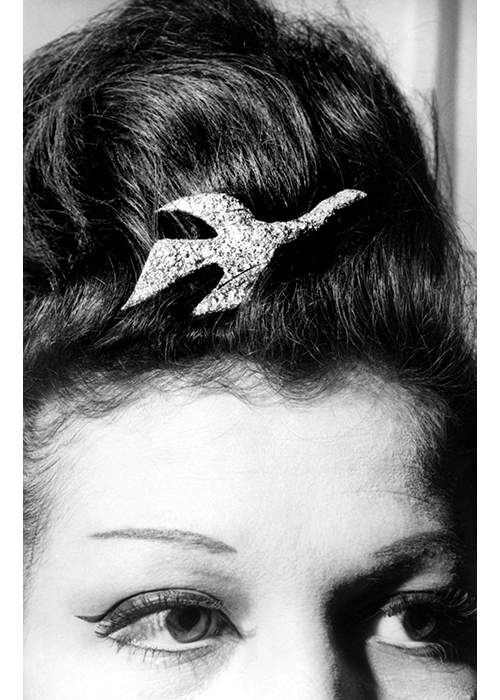

Flying Dove with Rainbow Background, 1952 by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Photo: Bridgeman Images © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2017

For de Castellane, the thrill in creating jewellery is in its longevity. “Jewels carry eternity,” she says. “I love the idea something that has been worn on your skin might transfer to whoever wears it next. There’s a magic in it.” And truly there is a sort of sorcery in how she breathes life into her stones. Like her heroine, Mary Blair, she has a rare skill for finding personality in the inanimate.

There is a sorcery in the way she breathes life into her stones

It is teasing out the personalities of the stones and creating narratives for them that work is about for de Castellane. “It’s like a little story,” she says. In her own collections these stories are bigger, wilder and sometimes quite ferocious. For Dior, they are gentler. “I like the idea of a very naïve world,” she says of her work for the house, “where the world is beautiful, everything is OK, there is no war, people never have illnesses, and everybody can eat what they want.” It’s also a chance for her to loosen up the “sometime serious” reputation of Christian Dior, and “make him a little more punk”.

Work, for this designer, shouldn’t be taken too seriously. “I can’t bear when people aren’t happy at work – it’s like a tyranny, a perversity,” she shrugs. And then offers up a grin as wide as the Cheshire Cat’s. “I like the idea of the game,” she says. “And having a bit of fun.”

Sketch by Victoire de Castellane of herself with Monsieur Dior.

Chanel’s dazzling new collection draws on the ancient Japanese craft of Maki-e

Two cultures combine in Chanel’s latest fine jewellery collection in which the classic high-jewellery skill of stone setting meets a traditional lacquer technique first perfected more than 1,000 years ago. Maki-e, a Japanese art form meaning “sprinkled picture” was first developed in 784AD and became a central decorative feature of the Edo period (1615-1868). The technique – in which slivers of natural resin and mother-of-pearl inlays are lacquered in a shimmer of gold or silver powder – is one of the great Japanese decorative crafts, and the artist Yuji Okada one of its leading practitioners. Okada, who teaches in Kyoto and works alongside his son, created three pieces for the Plume de Chanel collection: a brooch, earrings and a necklace (pictured). The “Artistic Collier Feather” is fabricated in 18 carat white gold and set with a 4.01 carat pear-cut diamond, two round-cut diamonds, with a combined weight of 2.51 carats, and a further 1,300 brilliant-cut diamonds totalling 29.32 carats. But its star quality is Okada’s feathery centrepiece, a black lacquer disc, no bigger than a baby leaf and brilliantly glossy, all set off with mother-of-pearl. JE

Artist jewellery is enjoying a renaissance. Aimee Farrell looks at its most captivating – and collectible – creations, from Man Ray’s mega earrings to Georges Braque’s brooches

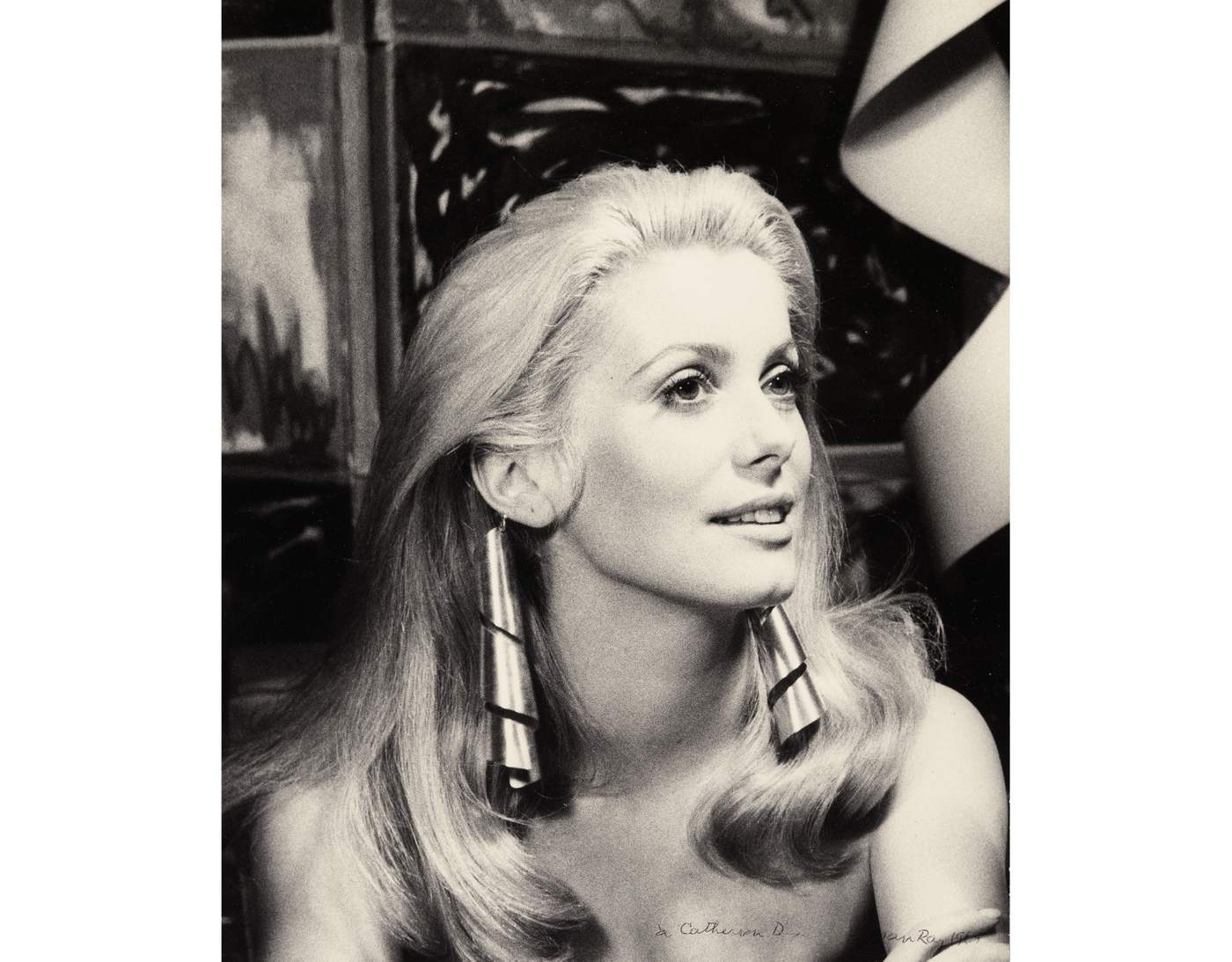

Catherine Deneuve wearing Man Ray’s Pendantif-Pendant earrings in a photo by the artist, 1968. Photo: Sotheby’s France/ArtDigital Studio © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017

Artist jewellery is enjoying a renaissance. Aimee Farrell looks at its most captivating – and collectible – creations, from Man Ray’s mega earrings to Georges Braque’s brooches

Catherine Deneuve wearing Man Ray’s Pendantif-Pendant earrings in a photo by the artist, 1968. Photo: Sotheby’s France/ArtDigital Studio © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017

Fashion has long been in thrall of artist jewellery. In the 1930s, couturier Elsa Schiaparelli commissioned her circle of artist friends including Jean Cocteau and Alberto Giacometti to create experimental jewels for her collections; art world fashion plate Peggy Guggenheim boasted of being the only woman to wear the “enormous mobile earrings” conceived by kinetic artist Alexander Calder; and Yves Saint Laurent, a generous patron of the French husband-and-wife artist duo “Les Lalannes” summoned Claude Lalanne to conjure a series of bronze breast plates, akin to armour, for his dramatic autumn/winter 1969 show.

So when Maria Grazia Chiuri enlisted Lalanne, now in her nineties, to devise the sculptural copper jewels for her botanical-themed Christian Dior Couture debut this year, she put artist jewellery firmly back on the agenda. “The fashion world is finally waking up to artist’s jewellery again,” says the London gallerist Louisa Guinness, a champion of the genre who deals in jewels by painters and sculptors both old and new. One of a handful of gallerists, including Elisabetta Cipriani and Didier specialising in artist jewellery, Guinness is doing a book on the subject, titled Art as Jewellery, due out this year. She recently loaned pieces from her vast collection to accessorise the Victoria Beckham AW17 catwalk show. “Fashion designers are always looking for something original and different, and art jewels are utterly unique,” says Guinness, who set up her eponymous gallery in 2002. “It’s exciting.”

Georges Braque’s Circé, 1962 brooch. Braque jewellery courtesy Diane Venet; all other jewellery shown here © Louisa Guinness Gallery

But why has artist jewellery been overlooked for so long? The simple fact is that many people have no idea that artists as varied as Picasso, Man Ray and Max Ernst ever made jewels. Created sporadically, often in small batches, their works are incredibly rare. But with more art fairs and shows than ever, the pool of collectors is gradually growing – and with it the prices. A few years ago, a brooch by Salvador Dali, “The Eye of Time” sold in London for around £75k, before being re-auctioned months later in Manhattan for approaching £1m.

Yet, strange as it sounds, part of the jewellery’s appeal remains its relative affordability: “Not many people have £100m to spend on a Picasso painting, but you can get a masterpiece of his artistry in jewellery for a fraction of the price,” explains Andres White Correal, Sotheby’s senior director of international business development jewellery, a more profitable division than contemporary art for the first time in 2016. “It’s taken an enormous amount of time to convince people of its intrinsic value,” he says. “Buyers usually want to know how many carats the stone is, or how precious the materials are. But the more other prices rise, the more art jewels become a viable means to step into collecting.”

For Guinness, who counts Ed Ruscha, Anish Kapoor and Gavin Turk among the contemporary artists whom she has persuaded to create jewels, these works have a value that goes beyond investment potential: “Artists are more interested in the conceptual idea and the form of a piece than simply creating beautiful jewellery,” she says, pointing to Calder, who made more than 2,200 jewels, fashioned from copper wire, pieces of broken glass and even cutlery. “Artist jewellery is about experimentation,” she says. Guinness also recommends the artful display of these wearable sculptures: “If you can hang a Picasso canvas on your wall then why not a necklace?”

Power and purity, influence and chastity – nature's most mysterious gem takes on many guises, says Chloe Fox

I first fell in love with pearls the very same day that I fell in love with literature. I can remember exactly where I was sitting – on a warm, sun-drenched spot of carpet under a window in my grandmother’s house. I can remember the sound of the birds outside, and the smell of the pages of the book that I had found on a dusty shelf. I liked its title – there was magic in it – and its promise to take me to another world.

Tender is the Night did not let me down. I was transported, instantly, from the English countryside to the French Riviera. I sheltered under a broad umbrella on the beach, watching a beautiful group of people – and one woman in particular – basking in the burning sun.

Margarete Penz, 1926 © Atelier Angelo/ullstein bild via Getty

“Her bathing suit was pulled off her shoulders and her back, a ruddy, orange brown, set off by a string of creamy pearls, shone in the sun.”

Even today, all these years later, this image takes my breath away. The glamour of it, the fragility, the hint of a secret waiting to be uncovered…

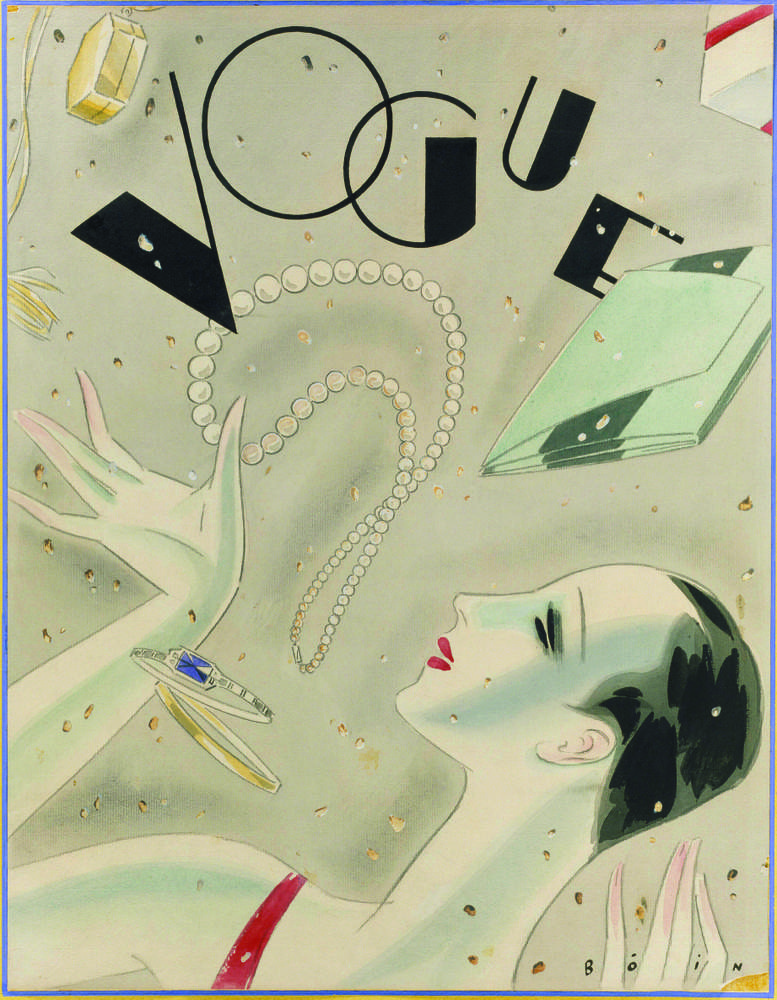

Vogue illustration © Photo by William Bolin/Conde Nast via Getty

F Scott Fitzgerald was certainly not the first author to use pearls to cast a trembling light on a mysterious muse. In his epic Iliad, believed to have been written in the mid-8th century BC, Homer draws the reader’s eyes to the Goddess Juno’s face with a shimmering image: “In three bright drops, her glittering gem suspends from her ears.” Over 2,000 years later, Max Beerbohm’s eponymous heroine Zuleika Dobson winks at her reader with her choice of jewels. “From her right ear drooped heavily a black pearl, from her left a pink; and their difference gave an odd, bewildering witchery to the little face between.”

More than any other gem, the pearl has historically been imbued with the power to tell a story. In the main, this is bound up with its own origins. For a pearl, like the best stories – like truth itself (or pearls of wisdom, indeed) – cannot be found without looking. As John Dryden observed in his 17th century poem, All for Love, “He who would search for pearls must dive below.”

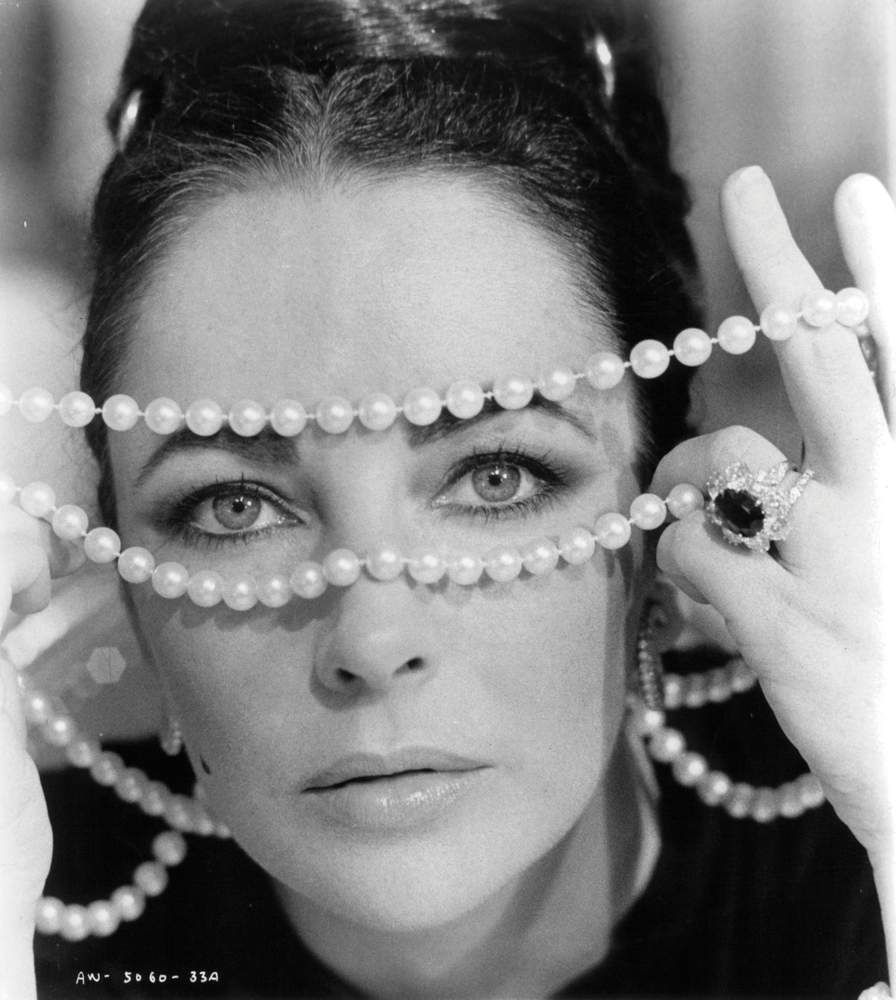

Elizabeth Taylor in ‘Ash Wednesday’, 1973 © Photo by Paramount/Getty

A hazardous endeavour, that for centuries involved ropes, stone weights and a great deal of trust between a diver and his mate in the boat above, pearl diving was seen, by early Islamic pearl hunters in the Arabian Gulf, as a test from God; the pearl a reward for the true believer. Century after century, across culture after culture, pearls have fascinated humanity, not least because of the mystery surrounding their creation. Early Hindu mythology held that pearls were made from dewdrops that the molluscs absorbed when they rose to the surface of the sea at night to breathe. Ancient Greeks considered them the result of lightning strikes. To the Romans, they were the frozen tears of gods.

A pearl will shine its light on anyone who will have it

The truth, as is sadly so often the case, is much more prosaic. When a foreign body is caught inside the shell of a mollusc (not just oysters – Who knew? – but also clams and mussels), the tender flesh is irritated into secreting a protective substance. Over time, this substance solidifies into layers of nacre. If a genuine pearl is cut in half, it can be seen to be made up of rings, just like the trunk of a tree. The more layers a pearl has, the more capable it is of refracting the light and basking its wearer in that wonderful iridescent glow.

But forget its excretal origins. It is the rarity of a perfect pearl that is the secret of its allure. While only one in every 2,000 oysters produces a pearl, only one in every 10,000 of those is deemed round enough, flawless enough, to be used as a jewel.

And herein lies the true power of the pearl. Because the pearl, over and above all else, is a flawlessly formed paradox, a priceless piece of perfection borne of a routine physical function. Simple and mysterious, the pearl has, over time, also added layer after layer to its own story, becoming a tiny emblem of a much bigger picture.

Woman with Pearl Necklace, 1942, by Henri Matisse (1869-1954). Archives H. Matisse © Succession H. Matisse/ DACS 2017

Take a walk through the annals of history, and you will find the simple pearl reigning supreme. A marker of luxury until the Medieval period (as a sign of her wealth and power Cleopatra famously dissolved a priceless pearl earring in a glass of wine and drank it), it then began to be viewed as a Christian symbol of purity and chastity. Here, after all, was a gem that Matthew deployed in his New Testament book to signify the great value of the Kingdom of Heaven (“The kingdom of heaven is like a merchant in search of fine pearls”, Matthew 13:45).

As time passed, the gems’ own capacity for miraculous conception saw them naturally associated with the Virgin Mary, a link which was then exploited by the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I. A passionate pearl enthusiast, Gloriana – whose own father Henry VIII had used pearls (most notably in Hans Holbein’s famous 1536 portrait of the king, codpiece and all) to advertise his virility – had pearls painstakingly sewn into all of her clothes to emphasise her purity. Customarily, she also wore seven or more ropes of large, fine pearls, the longest of which extended to her knees. Less than half a century later, in 1649, Charles I deployed the pearl as a signaller of his own innocence and purity when he went to his execution wearing a single pearl earring.

Coco Chanel, Paris, 1936 © Lipnitzki/Roger Viollet/Getty

Influence and chastity, power and purity; the pearl’s real secret weapon is its ambivalence. Because, with ambivalence, comes power; the power for the wearer to be exactly who or what they want to be. Thus a debutante can be a beautiful innocent, quivering at the beginning of her adult life, and Rihanna can be a knowing minx; Margaret Thatcher can be a woman in charge and Marilyn Monroe (who wore the same simple string of Mikimoto pearls that her one true love, Joe DiMaggio, gave her on their honeymoon to their divorce hearing just nine months later) can be a woman on the edge.

And staring boldly but trepidatiously out of the canvas of Johannes Vermeer’s celebrated 17th century oil painting, The Girl with the Pearl Earring can be all of these things, and yet none of them.

Fashion, that cultural magpie, has enjoyed an enduring love affair with the pearl; a tryst that was cemented, and democratised, by Coco Chanel, a woman with her own mysterious origins. As Christian Dior once mused, not without a whiff of resentment, “With a black pullover and ten rows of pearls, she revolutionised fashion.” Despite being presented with a yard of real pearls by her lover the Duke of Westminster every birthday and Christmas, Chanel was more than happy to play with the fake variety. In the decades since, as climate change and overfishing have made the uncultivated pearl a rarer and rarer find, the fake pearl has continued to reign supreme on catwalks and red carpets the world over.

Rihanna performs at the Victoria’s Secret show, New York, 2012 © xposurephotos.com

With none of the hardened snobbery of the diamond, the pearl will shine its light on anyone who will have it, be it the Duchess of Cambridge or Dita Von Teese. It is just as happy to wink and flirt, as it is to curtsey and nod. But what it will always do, however it’s worn, is allude, and speak of something beyond itself I read Tender is the Night in a single sitting; a whole, blissful day lost to literature. Underneath Nicole Diver’s beautiful brown back, set off by a string of creamy pearls, was indeed a heart full of secrets and suffering; layers of life hidden beneath the stillness, drawing me deeper and deeper in, until there was no turning back.

Marilyn Monroe hosts a press party at her home in Los Angeles, 1956 © Earl Leaf/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

Marilyn Monroe hosts a press party at her home in Los Angeles, 1956 © Earl Leaf/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

‘Talk to me Harry Winston, tell me all about it!’ sang Marilyn Monroe in ‘Gentlemen Prefer Blondes’. Jewellery has always played a central role in cinema: Audrey Hepburn’s Holly Golightly chose to have ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’, while Richard Gere gave Julia Roberts a $250,000 ruby choker in ‘Pretty Woman’. Today, those jewels are as likely to shine on the red carpet as they are on the big screen. Grace Cook looks at the most sparkly associations in history

Bulgari

“Elizabeth Taylor was the first real red carpet diva,” says Bulgari’s creative director Lucia Silvestri. The relationship between the actress and jewellery house began in Rome in 1963, at the same time as her love affair with Richard Burton. In the city to film Cleopatra, Taylor would visit the house’s founder Gianni Bulgari in the nearby Condotti store on her breaks. The store became a favourite hideaway for the couple seeking to escape the paparazzi (they even enjoyed exclusive use of a secret entrance). Bulgari soon became testimony to their tempestuous relationship: Burton’s many gifts to Taylor included a 60.5 carat Colombian emerald necklace which Taylor wore at their first wedding in 1964. And long after their divorce.

Sophia Loren was one of the house’s early ambassadors. More recently Sienna Miller, Nicole Kidman and Keira Knightley have worn Bulgari on the red carpet. Many of the pieces have glamorous pasts: the emerald, sapphire and diamond necklace worn by Knightley to the 2006 Oscars was created in 1967 for the Shah of Persia, while the fabled Serpenti necklace has charmed everyone from Julianne Moore to Naomis Watts and Campbell. “Movie stars are now part of our DNA,” says Silvestri.

De Grisogono

Founded in Geneva in 1993, De Grisogono has dressed aristocracy and actresses alike. Models Bella Hadid, Naomi Campbell and Jourdan Dunn favour its colourful diamonds and contemporary designs, while royals including Prince Emanuele Filiberto of Savoy are friends of the house. In 2001, founder and creative director Fawaz Gruosi cemented the brand’s place at the Cannes Film Festival with the launch of a lavish party which takes place at the Hôtel Du Cap-Eden-Roc. Last year, among the guests were Leonardo DiCaprio, Chanel Iman and Karlie Kloss, who wore jewellery pieces made up of over 1,000 diamonds. “The success is due to the beautiful people and jewellery,” says Gruosi. “The key is to mix celebrities, royal subjects and friends, all on one very glamorous evening.” De Grisogono’s Gypsy earrings – a cluster of intertwined ellipses embedded with sparkling gemstones – has racked up impressive red carpet mileage having been worn by Kloss (pictured, in 2015) and Charlotte Rampling. Gruosi is as much a regular of the carpet as his baubles: in recent years he has accompanied Natalie Portman and Heidi Klum to events.

Harry Winston

Known during his life as the “jeweller to the stars”, Harry Winston revolutionised the red carpet in 1944 when he became the first jeweller to loan diamonds to an actress for the Academy Awards. The star in question was Jennifer Jones, who went on to win the award for best actress for The Song of Bernadette. The house has continued to dress red carpet royalty ever since. Harry Winston jewels have proven to be something of a good-luck charm for its wearers: Scarlett Johansson, Gwyneth Paltrow and Jessica Chastain have all won in Harry Winston – Chastain wore a total of $3m worth to collect the 2013 Best Actress Golden Globe for her role in Zero Dark Thirty. The house also claims ownership of the world’s largest orange diamond, which was transformed by the New York-based maison into a “pumpkin diamond ring” and worn by Halle Berry at the Academy Awards in 2002 – the year she won the award for best performance by an actress for her part in Monster’s Ball.

Chopard

Chopard’s glittering association with the Cannes Film Festival dates back to 1997 when its co-president and creative director Caroline Scheufele redesigned the trophy for the festival’s top prize, the Palme d’Or. Four years later, the house launched the Trophée Chopard, given each year to recognise and encourage the careers of two young actors. And for the past decade the house has created a dedicated haute joaillerie red carpet collection of designs numbered to match the edition of the year’s festival. This year has found the house partnered with Rihanna on a 70-piece collection inspired by the singer’s Bajan roots, and featuring megawatt orange sapphires and paraiba tourmalines that evoke the island’s lush tropicana. Cannes’ la Croisette has also become the platform for Chopard’s Green Carpet Collection. Launched in partnership with Livia Firth in 2013 to promote sustainable luxury, the collection uses only fair-mined gold. Last year, the house introduced its first collection of ethical gemstones with a 53 carat Zambian emerald and diamond necklace, worn by Julia Roberts, and a pair of 18 carat pear-cut emerald and white gold earrings worn by Julianne Moore.

Saints and saviours, the spirit of Dolce and Gabbana’s fine jewellery begins with all things sacred. Interview by Jo Ellison

It was always going to be different. Dolce and Gabbana first unveiled their high jewellery collection, Alta Gioielleria in 2013 to accompany the launch of their couture-line collections. The twice-yearly collections fast became a unique event in the fashion calender, staged at an exclusive location and attended only by a select number of invited clients. Just like the fairytale clothing, the jewellery is big, bold and fun, combining baroque decadence, gothic symbolism and religious iconography in one-of-a-kind pieces which are both wonderfully kitsch and breathtakingly beautiful.

Whereas much of the jewellery world is dominated by a rather germane conservatism, Alta Gioielleria has a playful irreverence. Collections have included huge golden bird-of-paradise earrings, necklaces strung with gem-encrusted crucifixes and giant technicolour flowers. The designs are a hectic hybrid, combining marquetry, enamelling or filigree techniques, a vibrant colour palette and vast, rare gemstones. In the exuberant spirit of Dolce and Gabbana style, more is more is more.

Sicily, 1975 © Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos

The designers’ jewel designs are perhaps a product of their professional naivety. Neither is a trained jeweller, and the pieces are defined by the mood of the collections rather than the cost or availability of a particular stone. “It’s important that the jewellery is in harmony with the dress,” explained Domenico Dolce after the Alta Moda show which was staged in the workshops of La Scala, Milan, in January. “For us, it’s not just that you buy our jewellery, the jewellery should be complimento with the dress. The jewellery is made with the same inspiration as the clothes, because we love the connection.”

Oftentimes, his customers are more cognisant of the market than he is. “We sell all the big stones, the classic pieces,” he continued. “It’s a good market, because the customers understand the stones. I don’t want to know the price, because when I know the price, I want to die.”

As with their clothes, Alta Gioielleria is a synthesis of all the things Dolce and Gabbana cherish: the romance of the Sicilian widow, the opulence of Renaissance Italy and, most significantly, the iconography of the Roman Catholic church. “We present one message,” says Dolce of the designers’ world view. “We love huge jewellery, the Renaissance, the beauty of Italian frescoes and the paintings of Raphael or Michelangelo. We love Sicilia. Maybe we are a bit romantic or too boring but this is our culture. This is our myth. It’s very strong, it’s very romantic. And it’s always about the sacred.”

Crucifixes and images of the Madonna are well known to those familiar with the Dolce look. “It’s our DNA,” says Dolce who wears a long leather thread on his wrist strung with medals of patron saints and the Virgin Mary. “We grew up with the mamma going to church every Sunday morning. I’m a Catholic and I’m devoted to the Virgin. Which isn’t to say that my culture is the best or the only one, simply that I love and respect it.”

The designer’s holy inspirations take many forms: a tiara might recall a church altar; gowns are drawn from saints’ dresses seen at the holy festivals; intaglio rings and crosses appear everywhere. Some might frown at the idea of such spiritual relics being reimagined in the realm of high commerce, but for Dolce it’s all meant in good faith. “I believe in my devotion,” he explains, “but obviously my faith has a more private dimension also. We don’t create serious devotional pieces.”

Dolce and Gabbana Alta Gioielleria pieces at the house’s Spring 2017 Alta Moda show

Though the designers act as magpies, welding the most magnificent features of their heritage into their own creative narrative, they’re wary of taking too copyist an approach. They throw in some paste, or “fake” jewels, to give everything a modernity – and their affections for more modern icons, like Justin Bieber and Selena Gomez, are entwined with their traditional devotions. “When you’re too precise you can make something too retro,” says Dolce. “We love working in a different way, to mix the age, the style, and come back with something new. Traditional materials can be too heavy, and then customers don’t want it. It has to be easy.”

Ultimately, however, the Alta Gioielleria pieces, like the clothes, will become part of someone else’s culture and someone else’s story. According to Dolce, this is the most fundamental feature of his design. “You need to understand what people are dreaming of,” he explains. “I think of this all the time when I design. How each look will have one life, one home, one owner…”

Dolce’s references are only part of a story. “The pieces are nothing without the character,” he says. “We propose, but at the end of the day, people are themselves. The customer reinvents it. We just help them along that journey. Because we want the pieces to live”.

Through her fascination with art and architecture, Gaia Repossi has injected a modern spirit into a century-old jewellery house, writes Carola Long

Gaia Repossi © Antoine Doyen

‘The starting point for a design usually comes from a reference – say a specific architectural hook by Frank Lloyd Wright, or Donald Judd’s furniture,” says Gaia Repossi. This year marks her tenth anniversary as creative director of the 97-year-old jewellery house founded by her family, and she is explaining her evolving creative process over mineral water at London’s Chiltern Firehouse restaurant. Inspiration is everywhere – she’s just spotted the twisted trunk of a giant pot plant which would be a good basis for a cuff – and the art world is a particularly rich source of ideas.

You won’t find her in the Louvre sketching marble busts, though; the 31-year-old favours modern art and photography. In particular she is drawn to work by Judd, Franz West, Alexander Calder, Wolfgang Tillmans, Juergen Teller and Hiroshi Sugimoto, whose studio she recently visited. She says, “the subconscious has a huge influence in the creative process because maybe you don’t like the artist at first, and little by little you absorb it then poof! It comes.”

The influence of modern art is apparent in Repossi’s jewellery even before specific references reveal themselves. The former painting and archaeology student’s designs are sculptural, minimal and have a captivating tension between the strict and the playful. Stars, flowers, or baroque curlicues are nowhere to be seen in her rings or bracelets.

The house’s modernity is underlined by the newly redesigned store on Paris’s Place Vendôme. Designed by architect Rem Koolhaas and his OMA team, the three-storey building eschews the inside-a -jewellery box feel of a more classic boutique in favour of a rich futurism. Myriad reflective surfaces, many in a signature rose gold colour, are combined with features intended to fuse architecture and display.

Rem Koolhaas’s Repossi store, Place Vendôme, Paris © Cyrille Weiner

“The store was inspired by the jewellery and the jewellery was inspired by the store,” says Repossi of its design which in turn attracts architecture students who come to appreciate Koolhaas’s work, and sometimes end up buying a trinket or two. It also houses furniture by Judd, which she collects. In her Paris home (she spends time too in LA with her boyfriend the artist Jeremy Everett), she has a bed, tables, stools and a bookcase by the late American artist’s studio. “It’s an amazing experience to live with his work,” she says, in her soft Parisian whisper.

Judd’s work was also an inspiration behind the Berbère collection. Launched in 2010 it included a range of earrings and rings with ribcage-like stacks of semi-circles that spawned a multitude of copycats. She was particularly drawn to the room full of aluminium Judd boxes at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, a museum founded by the artist. Repossi explains, “they have an infinite system, thousands of variations, and I work with systems a lot: certain motifs or colour combinations that repeat throughout the collections”. Concepts from Judd’s geometric, repetitive structures were combined with images from Berber art and the tribal tattoos of the Tuareg, nomads inhabiting the Northern African desert. The result is a collection of rings and earrings with an armour-like, anatomical quality.

More decorative is the Suspensions collection, which looks to Alexander Calder. Requiring no piercing, these mobile-like earrings appear to float on their own. Repossi’s miniature structures are engineering puzzles, and can take time for the ateliers to perfect; the Serti sur Vide line with its rings composed of separate but connected bands, and diamond ear cuffs, took two years. Repossi says, “I have an Italian atelier who say to me, ‘Miss Repossi, every time it’s a new technique.’” Some ateliers panic, some love the challenge.

The secret of Repossi’s success is in balancing this artistic experimentation with adornment that compliments the wearer rather than overwhelms them. “For me what makes jewellery modern is something unusual, something a little bit unexpected but at the same time not necessarily a statement,” she says. “Jewellery can have a tendency to decorate, cover and suffocate. It should follow the body.” Tracing her sharp jawline with a finger laden with her slim rings, she notes that, “when we shoot an image sometimes the earring will create a certain line to complement the jaw, there are different rhythms and shapes which really work, like a prop reshaping the face.” This quality is particularly in demand with actresses on the red carpet. Isabelle Huppert, Tilda Swinton, Julia Roberts, Emma Stone and Alicia Vikander have all worn Repossi, as does the artist Cindy Sherman, who likes “the most modern pieces”.

This flattering effect is showcased in the new ad campaign by Juergen Teller. Repossi says she hopes that the shots are “almost like artworks” and they certainly underline the brand’s provocative, rigorous and intellectual core. Does Repossi consider her work to be art? She laughs that it would be “vanité, pretentious of me to say it is but you need an artistic sensibility to create an object with its own aesthetic. It’s an applied art. I hope my jewellery is nourishing and has an identity and a soul. I am attracted to artistic influences that combine with the practical needs of what I do. They create a beautiful visual world that I just swim in.”

Vivienne Becker explores how the majesty of the tiara has been exploited – and subverted

As muses go, the exotically beautiful, effortlessly elegant Joséphine de Beauharnais, Napoleon’s first and most famous Empress, hasn’t been given her due. She exerted huge influence on fashion – those classically inspired, high-waisted, goddess-like gowns and low-cut, ruff-frilled necklines – but an even stronger, far more enduring influence on jewellery. In particular the tiara.

Poetic, alluring and allusive, with its echoes of golden diadems of Imperial Rome, the tiara was the jewel she made her own, turning it into the ultimate symbol of feminine power and privilege, of fairy-tale transformation for future generations. Today that influence is revived, re-evaluated and re-invigorated by Chaumet, the place Vendôme master jeweller, whose founder, Marie-Étienne Nitot, became court jeweller to Napoleon Bonaparte. Joséphine’s style and taste still drive Chaumet’s creativity, and the tiara remains the heart and soul of its story; a story now told in an exhibition, Imperial Splendours, in the Palace Museum, Beijing (formerly the Forbidden City) through some 300 jewels, objects and artworks charting Chaumet’s course from its own imperial roots in 1780 to the present day.

The tiara was the scintillating star of the show, punctuating each era, and brought up to date with “Vertiges”, an arresting, contemporary tiara designed by 21-year-old Scott Armstrong. The Central Saint Martins student was the winner of a competition organised by Chaumet in collaboration with the London fashion college to create a tiara for the 21st century. Armstrong took Chaumet’s ongoing theme of naturalism, French formal gardens and Joséphine’s mad love for horticulture as the starting point for his dynamic, architectural tiara, in which ordered, geometric diamond lines and arcs are overgrown with a chaos of clustered green tourmalines and garnets.

Scott Armstrong’s Vertiges diadem. Chaumet, Paris

If Joséphine was mad about her gardens, her passion for jewels bordered on reckless obsession. Far more than a fashion icon or trophy wife, she understood the propagandist power of fashion, finery and jewels – especially jewels – to inspire confidence, loyalty and allegiance, to convey the pomp and majesty of Imperial might. Every one of the magnificent gem-encrusted parures made for her by Nitot was crowned with at least one imposing tiara. These she wore with great panache, as seen in her many portraits, often low on the forehead, countering their classical rigour and dignity with sumptuousness and sensuality. For Josephine the tiara was both a political and a style statement, she harnessed its power and re-invented its ancient, ritualistic associations for a new age, giving it a fresh fashionability and freedom of creative expression.

By the Belle Epoque, the tiara (now loaded with newly discovered South African diamonds) became the ultimate possession and status symbol of ladies of style and substance, their passport into society, essential wear at court, for smart dinners, soirées and the opera. Designs were lyrical, endlessly expressive, and Chaumet was the place to go for the “It” accessory of the day.

The house offered a vast choice of styles, as their design archives show, neo-classical, romantic and naturalistic. Then in the 1920s as the tiara morphed into the racy bandeau, geometric designs, in the prevailing Art Deco style, appear. The transformative beauty of the diamond tiara, the halo of light wreathing the face and head, also marked rites of passage, from American heiress into British aristocrat, from schoolgirl to debutante, and maiden into married woman – as etiquette decreed only married women could wear a tiara, a symbol of rank, status, elitism.

These deeply entrenched associations with wealth, power and privilege were seized on and subverted by the grunge generation, most memorably in 1995 by Courtney Love, at the Vanity Fair Oscars party. She paired her long ivory nightgown dress provocatively with a tipsy, twinkling crystal tiara, as if pulled from a dressing-up box. It was a way too of beckoning jewels back into fashion, with suitably grunge style shock and irony; the tiara became the cult accessory of a youth-powered fashion rebellion. In the same year, Gianni Versace won a De Beers’ Diamonds International Award for a diamond-set tiara, modelled by Madonna, the material girl, turning the social order on its head (pun intended).

Courtney Love at the Vanity Fair Oscars party in 1995 © Vinnie Zuffante/Getty

In 2015, as Saint Laurent reprised its seminal 1990s grunge slip dress, tiaras once again tripped down the catwalks – nostalgic, subversive, and blazing a new trail of head and hair jewels. While in Asia, the jewelled tiara is now highly prized as “treasure”; an instant heirloom, a shining symbol of success. Joséphine, Chaumet’s magnificent muse, would be proud.