If fashion is a reflection of our cultural preoccupations, the autumn-winter collections offer a curious view as to where the world is now. Not unlike a hall of mirrors in a fairground, designers have offered surprising new angles on well-familiar themes. The resurgence of craftwork, collage, a sense of collective endeavour and a make-do-and-mend sensibility are all powerfully felt this season.

Unsurprisingly also, in a world obsessed with President Trump, many designers have found themselves revisiting the signatures of Americana to unpick its sartorial codes. Some are nostalgic for its indigo denims, prairie-girl femininity and steel-tipped Rawhide swagger. Others have taken their cue from photographers like Edward Weston, Dorothea Lange or Richard Avedon to find its rawer edges and a grittier style. Simon Schama explores the wonder and woes of the mythic West in his ode to the cowboy on these pages.

Model Michaela Kocianova in a Picasso-inspired AW07 haute couture ensembles by John Galliano for Dior ©Guy Marineau

Other designers find inspiration closer to home. The catwalks were a colourful homage to the bright floral fabrics of the Arts & Crafts artists who first presented their decorative schemes in the late 19th century. Perhaps we all need extra cushioning from the outside world?

And then there are those designers who push the boundaries of their creative fields to challenge our notions of what clothing is at all. Charlie Porter looks at the evolution of the avant-garde, in art and fashion, and finds an entwined history. From Schiaparelli’s fur bracelet, to Gucci’s hair-lined loafers, Comme des Garçons’ snow-white cocoons or Balenciaga’s wing-mirror clutches, fashion’s more absurdist ideas are often the most magical. And surprisingly commercial.

Jo Ellison, Fashion Editor, FT

Grit, guns and grime – cowboy country has an irresistibly raw glamour. Simon Schama saddles up

Cowboys may not all die with their boots on, but after they’ve gone, their wardrobe, especially in the hat and shirt department, asks for proper respect. This was apparent at my father-in-law’s funeral where pride of place was given to his favourite hat which lay propped up on a table like a sacred relic. Just what brand of hat it was I’m not sure: not some fancy Stetson anyway, the kind of thing urban cowboys show off at country music concerts or in upscale bars in Austin and Santa Fe. It may even have been a straw hat which cattlemen wear more often than you’d suppose.

To say that my father-in-law Merrill was a cowboy barely begins to tell his story. He ranched and drove cattle most of his life; on his own land to begin with but when he lost that through all kinds of imprudence, grazing them on other ranchers’ spreads. To make ends meet he hunted mountain lion and was so good at it that Nevada made him its official lion-hunter for the northern division of the state, responsible for keeping the big cats off herds and flocks. Pretty soon you’d have to go a long way to find the odd lion that would come within miles of Merrill. At his funeral, one of his devoted riding buddies lauded him with a straight face as a “conservationist”, as if massive culling counts as looking after the best interests of the big cat.

Merrill was the kind of cowboy beside whom the TV gunslingers I grew up with – Tex Ritter, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, all howdy pardner and Pepsodent smiles – were just a bunch of sissies in buckskins and chaps. Merrill was a workhorse; which isn’t to say that he was slow and silent. He had charisma by the wagonload, a rosy weatherbeaten face with a slightly squashed little nose at its centre and sharp attentive eyes of the kind pulp fiction likes to call “gimlet”. He stood six foot and a lot more in his workboots, and when in the mood, could be a joker. Merrill’s idea of a fun was to emerge from the outhouse on Horse Mountain at a family reunion holding the neck of a dead rattler, chuckling while he let it be known that he thought he’d got the last one. He could raise hackles but also inspire devotion. After the funeral service in the little chapel, family and friends reassembled at a small cemetery on a hillside where his last best riding buddy read a poem (yes cowboys do actually write them). When he finished the verses, the friend opened the urn, sank his hand deep into Merrill’s ashes and then smacked it against his heart so that, for a moment, before a mountain breeze took it away, there was handprint of Merrill laid on the soft plaid of the cowboy shirt. This, he would have liked.

If this all sounds like a Western romance, the reality was, and is, often no fashion shoot in the High Chaparral: a life lived with dogs and horses but also with tanks of liquor, uncertain fortunes and eruptions of brutal temper.

Beef being too precious to serve up to the family, my wife and her siblings grew up on a staple (and detested) diet of fried bear and potatoes; though there was much canning of fruit and veg, and a summer ritual of hand-churning peach ice-cream. Inevitably there is a certain amount of human wreckage amid all those guns and trailers: teenage pregnancies, school drop-outs; and a lot of moving around too, back and forth across the California-Nevada line. This is the West which didn’t (and doesn’t) make it into the movies, though there were moments in Brokeback Mountain which ran reality fairly close.

But maybe invisibility is preferable to clinical ethnographic inspection of the kind recorded in the early 1980s when Richard Avedon took his camera to Texas. The results were published as In the American West. I knew Avedon a little from the time I was art critic of the New Yorker in the 1990s, liked him a lot personally and was in awe of his strongest work which often went beyond fashion shoots to document something profound about America. Something about his lighting – and printing – translated into a physical immediacy no one other photographer could even approximate. But In the American West seemed to me to misuse all those gifts with such tendentiousness as to betray the entire project. What was made physically immediate to anyone who could afford the steep price of a swanky photo-album was American carnage, degradation and despair, bundled into a package labelled “The West”.

It’s not hard to see that Avedon was engaged in some gratuitous over-correction for his fashion photography (which after all needed no apologies). The notion may have been to channel his inner Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, and to depict a kind of American social truth – guns, grit and grime – which the tinny glamour of the Reagan Zeitgeist, embodied in the brush-cutting Rancho del Cielo president, preferred not to be reminded of. The idea was entirely honourable but somehow the execution of it sank in an overflow of disgust. Even when their clothes were barely more than rags, Evans’s and Lange’s images of the Depression-era destitute, gaunt from hunger, often seen as families, was tenderly heroic and came from the same kind of hard-boiled empathy imprinted in the pages of James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Obviously Avedon wanted to sweep away any hint of the sentimental, but what he replaced it with was a bone-cold exercise in metropolitan superiority.

But then it’s striking that there seem to be no modernist painters or photographers who have captured the peopled West as distinct from its pure landscape, much less the true West of highways, gas stations and small town soda fountains. Even Edward Ruscha’s gas stations are strangely minus customers and cars. Ansel Adams and Georgia O’Keeffe loved the West but emptied it of humans when they made their art. Edward Weston folded his model and lover Charis Wilson into Oceano Dunes, her nude body rhyming with the shifting sand. But clothed on Wildcat Hill he catches her full of Western attitude, breeze-blown hair, pale and slender, clasping one arm with the other hand, barely containing the strength of character.

Charis, 1936, by Edward Weston, 1886–1958. Gelatin silver print Sheet: 24.4 x 19.4 cm. The Lane Collection, courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston ©Center for Creative Photography,

The University of Arizona Foundation/DACS 2017

You can find both Weston and Avedon in the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas. Contrary to bicoastal assumptions Fort Worth is one of the great art meccas of the United States, boasting arguably the most architecturally beautiful gallery in the country if not the world, Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum. Although just round the corner, Tadao Ando’s Modern Art Museum, sitting in its limpid reflecting pool runs it close. But Fort Worth also boasts another kind of art: the “Western apparel” emporiums lining streets around the old stockyards. The undisputed monarch of them is Cavender’s Stock Yards, its shelves lined with cowboy boots of every imaginable hide and colour; elaborately stitched and embossed, pointy-toed and high-heeled. To wear any of these masterpieces with jeans would be an act of disrespect unless the jeans – a 19th century invention not of the cattle ranges but the silver mining towns of the Sierra Nevada – are themselves making a statement. No you want to wear these beauties with a good suit though possibly not if your line of work is chartered accountancy or negotiating Brexit.

Once you’ve equipped yourself with a pair, along with a fine cowboy patch-pocketed shirt and a silver belt buckle you can mosey along to the Amon Carter Museum where it’s not all Frederic Remington bucking broncos. Some western painting, Charles Marion Russell’s admittedly romantic images of the Native Americans, made at precisely the time when the social reality had been destroyed, are still poignantly beautiful. John Mix Stanley, a generation before Russell, was more the real thing: explorer and painter, capable of making luminous, moving images of Indian encampments on the Prairies in the 1850s without any sort of condescension.

Amon Carter also has photos of another world in its last round-up time: pictures of west Texas taken in the early decades of the 20th century by Erwin E Smith who was both true cowboy and exceptionally gifted photographer. Some of his shots – moody profiles, off and on horseback – passed into the industry of cowboy platitudes deep in Marlborough country, and a number of them must have been the models for the likes of Tom Mix and John Ford when they wanted to imagine movie range-riders. But Smith was capable of unforgettable singularities: a portrait of Tom Blasingame, a cowboy of legendary longevity who was still riding until, at 91, he dismounted, lay on the grass, crossed his hands over his chest and passed to the Last Round Up. The greatest of all Smith images – and perhaps of all Western images – is “Steer wrestler” (also in Amon Carter) with the animal and cowboy entangled in the dirt as if in a kissing embrace: a pose of stupendous muscular power on the part of both beast and man.

Steer wrestler with downed steer, 1920–35, by Erwin E Smith (1886–1947) ©Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Bequest of Mary Alice Pettis

Forty years ago I came close to an Erwin Smith moment. I was on horseback for the first time trotting through the Maroon Bells mountains in Colorado where I was putting in time roping and wrangling business executives who needed to know something about Machiavelli, Locke and (of course) Adam Smith. The afternoons were ours so there I was on an ancient, swayback mare moving very slowly since she clearly knew a greenhorn when she had one on her back, and periodically letting off foul eructations as we plodded the trail. But a Western epiphany approached when across a shallow gulch another rider, silhouetted in the sunset, waved his hat to me in salutation. Hi-ho Schama! What he shouted over the sagebrush, though, was not what I really wanted to hear: “That point you made about The Wealth of Nations this morning, professor, very shrewd I thought.” I sank deeper in my saddle; giddy-upped old swayback and to lift my spirits sang “Red River Valley” all the way back to the corral. “Come sit by my side if you love me/Do not hasten to bid me adieu/But remember the Red River Valley/And the cowboy who loved you so true”. From the response of her rear end I could tell old swayback wasn’t impressed. Wouldn’t you know, everyone’s a critic.

In a digital age the fashion collage has renewed appeal. We commissioned artist Seana Redmond to cut and paste the themes of the season

Contact sheets marked up in grease-pencil, Polaroids, sketches on napkins and scraps ripped from magazines: fashion is built on a tapestry of ephemera, and lots of bits of stuff. The designer mood board – that collage of materials, references and quotes, that informs the direction of a collection – is still one of the industry’s most powerful tools; while the photographers’ outtakes tell a story far removed from the glossy images that appear in print.

Once disregarded, or lost in the studio sweep up, these artistic artifacts have in recent years come to assume a rare value. When Cecil Beaton’s scrapbooks are exhibited alongside his famous portraits they offer a more intimate insight into his personality and the society the photographer inhabited than any silver gelatin print; Guy Bourdin’s Polaroids offer a glimpse into a world before the edit. A designer’s mood board says as much about a collection as the notes on its fabrications.

![Constructivist

‘I’m very influenced by old magazines such as Nova, and an obscure 1970s magazine called Destroy All Monsters, it’s home-made looking with collages and interesting effects. I collect vinyl too: some of the album art is really influential, particularly the Rolling Stones, New Order, Pulp, Blondie, Grace Jones and Pink Floyd – the graphics are just brilliant. The Roksanda show [far left] was perhaps the initial inspiration for this Constructivist collage because she used such angular lines and bold graphics. There were good geometries and colourways at Louis Vuitton [bottom right], Lacoste [centre] and Victoria Beckham [top right] also. Usually my collages start with something a bit softer and rounder, so these new geometric shapes were fun to explore.’ – Seana Redmond Constructivist

‘I’m very influenced by old magazines such as Nova, and an obscure 1970s magazine called Destroy All Monsters, it’s home-made looking with collages and interesting effects. I collect vinyl too: some of the album art is really influential, particularly the Rolling Stones, New Order, Pulp, Blondie, Grace Jones and Pink Floyd – the graphics are just brilliant. The Roksanda show [far left] was perhaps the initial inspiration for this Constructivist collage because she used such angular lines and bold graphics. There were good geometries and colourways at Louis Vuitton [bottom right], Lacoste [centre] and Victoria Beckham [top right] also. Usually my collages start with something a bit softer and rounder, so these new geometric shapes were fun to explore.’ – Seana Redmond](https://www.ft.com/__origami/service/image/v2/images/raw/http%3A%2F%2Fig.ft.com%2Fcc%2Fart-of-fashion%2Faw17%2Fmedia/collage_04-lr_bioo9qn.jpg?source=commercial-content-lambda)

Constructivist

‘I’m very influenced by old magazines such as Nova, and an obscure 1970s magazine called Destroy All Monsters, it’s home-made looking with collages and interesting effects. I collect vinyl too: some of the album art is really influential, particularly the Rolling Stones, New Order, Pulp, Blondie, Grace Jones and Pink Floyd – the graphics are just brilliant. The Roksanda show [far left] was perhaps the initial inspiration for this Constructivist collage because she used such angular lines and bold graphics. There were good geometries and colourways at Louis Vuitton [bottom right], Lacoste [centre] and Victoria Beckham [top right] also. Usually my collages start with something a bit softer and rounder, so these new geometric shapes were fun to explore.’ – Seana Redmond

Into this mix has arrived the fashion collage. While a number of artists, like Linder Sterling and Richard Prince, have been working in the medium for decades, a clutch of young creatives has given this simple art form a new fashionability. Patrick Waugh’s retro collages, which recall old fanzine spreads, are a huge part of the success of his BOYO studio. Kalen Hollomon, an Instagram artist, uses images shot on his iPhone in New York to create irreverent collages that poke fun at big brand advertising: he now has more than 100k followers and his work has appeared in US Vogue.

The art director and visual researcher Seana Redmond first started playing around with the cut-out-and-stick approach earlier this year. “As a researcher for stylists, photographers and designers, I sift through thousands of visuals every day to support their vision, putting together boards of pictures that help provide the inspiration,” says Redmond. “Looking at so many images, they can become hard to absorb, which is something a lot of us struggle with when we’re drowning in visual stimuli. Collage is a fun way to draw on my archive of references and use them to do something for me.”

Loose Threads

‘The craft theme lends itself really easily to collage, and needlecraft was a huge theme at the shows. Many of the images here are taken from the Maison Margiela, Alexander McQueen and Sonia Rykiel shows. Margiela felt very experimental: I love the home-made craftsmanship that sat at its heart. And the embroideries at McQueen were just beautiful’ SR

Initially done as a hobby, Redmond posted her pieces on Instagram and was soon receiving commissions to do collages. Her work is strong, graphic, feminine and quite sensual – fleshy body parts and fishnet stockings feature heavily. “The French really seems to respond to the images,” says Redmond who, likewise, looks across the Channel to Le Monde’s stylist Suzanne Koller and the designer Martine Sitbon, as well as Idea Books for inspiration.

“I like accounts that have a strong visual identity. But for me to be described as very feminine is pretty funny because I’m not very feminine at all.”

Redmond, a fan of the collage artists Katrien De Blauwer, from Belgium, and Danish Evren Tekinoktay, isn’t surprised that this old-fashioned medium has become popular now. “People respond to the home-made-ness of collage,” she says. “It’s such a strong visual aesthetic, it stands out in a digital environment. And there’s something authentic about seeing something handmade.”

![Patchwork

‘I think one of the reasons that collage is becoming more popular is that it makes an emotional connection. It’s the same with patchwork, or embroidery, as seen at Alexander McQueen [bottom right] and Balmain [centre]. These techniques have more resonance in the digital age when it’s harder to appreciate the time that might go into something. This season the Missoni and Loewe patchworks [bottom left] were especially strong, and graphic, so they really compliment each other when seen together.’ SR Patchwork

‘I think one of the reasons that collage is becoming more popular is that it makes an emotional connection. It’s the same with patchwork, or embroidery, as seen at Alexander McQueen [bottom right] and Balmain [centre]. These techniques have more resonance in the digital age when it’s harder to appreciate the time that might go into something. This season the Missoni and Loewe patchworks [bottom left] were especially strong, and graphic, so they really compliment each other when seen together.’ SR](https://www.ft.com/__origami/service/image/v2/images/raw/http%3A%2F%2Fig.ft.com%2Fcc%2Fart-of-fashion%2Faw17%2Fmedia/collage_03-lr_t3dvlo0.jpg?source=commercial-content-lambda)

Patchwork

‘I think one of the reasons that collage is becoming more popular is that it makes an emotional connection. It’s the same with patchwork, or embroidery, as seen at Alexander McQueen [bottom right] and Balmain [centre]. These techniques have more resonance in the digital age when it’s harder to appreciate the time that might go into something. This season the Missoni and Loewe patchworks [bottom left] were especially strong, and graphic, so they really compliment each other when seen together.’ SR

Asked to create a series of collages that reflected the themes of the AW17 collections for the Financial Times, Redmond was struck by the season’s bold print and colour. “I was really inspired by the Joseph shows for the prints and the relaxed slouchy tailoring … it looked very considered. And I loved the injection of bold print. I also enjoyed the graphic prints, palette and the retro feel at Miu Miu – ideal for collage making – and the cool girl denims at Calvin Klein and APC.”

True to her form, Redmond also loved Prada, where the principles of collage were applied to both the clothes – in which floral mohairs, tweeds and leathers slicked with retro-looking poster prints were patchworked together in bold colourful looks – and the set, which recalled the walls of a teenage girl’s bedroom. The entire stage was tacked up with overlapping pictures, posters, passport photo booth prints and cut outs. Sticking things together never looked so cool. JE

Peter Pilotto’s posse. Front: Peter Pilotto. From far left: furniture designer Martino Gamper; Andreas Schmid of antiques store Schmid McDonagh; painter Peter McDonald; artist Francis Upritchard; lighting designer Bethan Wood; glassblower Jochen Holz; and Christopher de Vos

Peter Pilotto’s posse. Front: Peter Pilotto. From far left: furniture designer Martino Gamper; Andreas Schmid of antiques store Schmid McDonagh; painter Peter McDonald; artist Francis Upritchard; lighting designer Bethan Wood; glassblower Jochen Holz; and Christopher de Vos

They started as friends, they soon became collaborators. Grace Cook meets the artists, furniture makers, curators and creatives who make up three designer clans. Portraits by Gabby Laurent

Peter Pilotto and Christopher de Vos launched the Peter Pilotto label in 2007. Renowned for their digital prints and strong use of colour, they won the BFC/Vogue Fashion Fund in 2014, and the Swarovski Collective Award the following year.

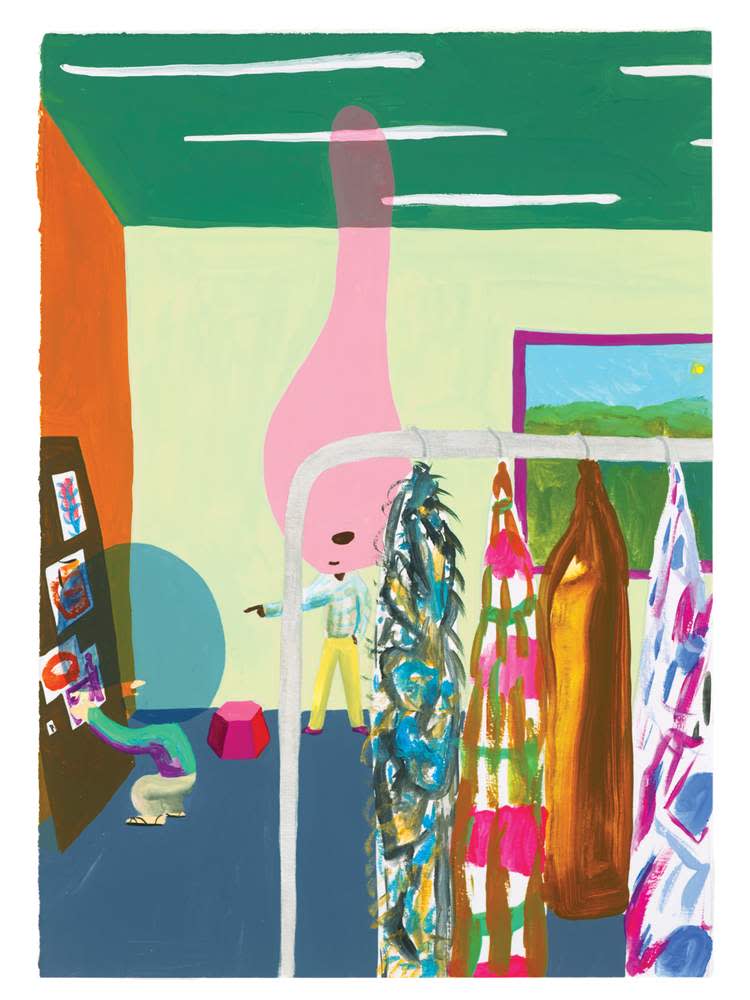

Peter Pilotto’s creative family was born seven years ago when the furniture designer Martino Gamper made a rail for Pilotto’s Dover Street Market concession. Pilotto became friends with Gamper and his wife, the artist Francis Upritchard, and more introductions were made. Soon the group of friends were trading clothes for artworks. Fast forward to AW17, and the tight-knit artistic circle worked together on the Peter Pilotto catwalk show.

Staged in the Waldorf Hotel in London, the space was filled with an eclectic mix of furnishings and objects – in glorious technicolour. Guests sat on Gamper’s rainbow-hued stools, drinking juices from glasses made by Jochen Holz, while models stomped a runway filled with fringed shagpile rugs by the designer Max Lamb. The invitation was painted by Peter McDonald – a scene he secretly drew after visiting the studio to buy a gift for his wife.

Each friend donated pieces for the show. “There wasn’t a strategy behind it,” says Pilotto’s partner and the label’s co-creative director Christopher de Vos of the collaboration. “While we were all talking, we thought, oh why don’t we do this and that, and ‘Bethan, bring in your lamp…’”

“All our friends are in art and design, and what we have at home or here in the studio or in their homes… these are real things that are super beautiful and super creative,” says Pilotto, of this coming together. “We just thought, these are the things that surround us constantly.”

Their friends – Upritchard and Bethan Wood, as well as the artist Caragh Thuring – regularly wear the brand. “We met a few of our artist friends through collectors because they would buy a Peter Pilotto, but they would also collect our friends’ art or their design pieces or furniture,” says de Vos. “It’s interesting, that universe of London, how it connects people together.”

Often they find themselves working with similar aesthetics. “Before pre-fall, Francis came to the studio and she was like, ‘You’re doing a painted check like that? That’s exactly what I just saw at Caragh’s studio’,” says Pilotto. “We are all so aligned.” Upritchard found a piece of unused fabric in the Pilotto studio, and turned into a sculpture that was exhibited at the Venice Biennale. Upritchard also collaborated on the SS17 collection: a holiday in Greece formed the jumping off point.

Peter and Christopher by Peter McDonald, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry, London

Part of the decision to show in a big open space at the Waldorf was due to members of the group commenting that previous runway sets had prevented the audience from properly seeing the clothes. “They analyse really carefully how their work is displayed, whether it’s exhibitions or at the Biennale,” says Pilotto of their contribution. “It’s not fashion, but it’s still so relatable.”

The friends are often found weeding in Upritchard’s allotment together, or travelling everywhere from Scotland to the Tyrol and Marrakech. “We just enjoy collaborating because we get to see each other more,” says Pilotto. Holz created a twisted glass earring for AW17 – the first piece he has created to be worn. Special editions of Gamper’s stools will be available on the Peter Pilotto website. Wood’s lamp, previously only exhibited in galleries in Europe, will be used in the brand’s internationally travelling pop-up store, which launches in London next month.

Working together allows each artist to reach new clients, without it ever having to be a calculated marketing decision. “I had so many requests from customers wanting this rug that we found a way of making it available,” says de Vos. “You need to create that emotional bond with your people, to let them into your world and into what inspires you,” he explains. “Experience is so important. I feel that is what is modern.”

Christopher Kane’s clan. Clockwise from top: art director David Bailey Ross; Christopher Kane; and co-creative director Tammy Kane

Christopher Kane’s clan. Clockwise from top: art director David Bailey Ross; Christopher Kane; and co-creative director Tammy Kane

Christopher Kane launched his eponymous label in 2006, in partnership with his sister Tammy. In 2013, he received investment from Kering, and opened his flagship store on London’s Mount Street the following year. Kane is often inspired by art: he incorporated the UFO illustrations of the late artist Ionel Talpazan into his AW17 collection.

Christopher Kane’s favourite artwork is one of his own: a picture of his mother, done spontaneously on Boxing Day two months before she passed away. Initially intended as a joke, it was done on neon pink paper with glitter pens and crayons alongside his niece Bonnie, aged five. “Art doesn’t need to be by a famous artist,” says Kane. “Before you learn to read and write, you’re given a pen to draw with. I can even find art in Bonnie’s drawings. I think they’re good.”

Kane attributes his democratic approach to art to his childhood in the Scottish industrial town of Newarthill: “It was very dark and very grey, and there was not much to do except draw.” And he keeps his collaborators close: his sister Tammy, five years his senior, is co-creative director at the brand; a close family friend, David Bailey Ross, who went to college in Glasgow with Tammy, is art director. Having two other Scottish accents at the helm is essential, says Kane. “My perspective on things like art is different from other people’s… David is from the same background as us. We’re not Oliver Twist but it was hard. Other people [in this industry] have grown up in New York or London…”

Works by Galerie Gugging artists on display in the Christopher Kane Mount Street store

All three are inspired by what Kane describes as the “real world”: they get each other’s references. They love Tracey Emin’s “My Bed” because there is “no fantasy” with it. He takes the same attitude in his design: elevating the everyday. His AW16 show, Beauty Expired, was inspired by a rubbish tip. “We made a coat look like a cardboard box [in corrugated leather],” he says. “We created shredded flowers to look like rubbish and put them on hemlines… Yes she’s wearing a bin bag, but it looks great.”

The Kane siblings think of themselves as “outsiders” and Kane’s work has often drawn on Outsider art. For pre-fall, he collaborated with Galerie Gugging – a psychiatric “house of artists” that provides care to creatively talented residents. “There’s this artist called Judith Scott, a mentally ill, Down’s syndrome woman who was abandoned by her family,” says Kane. “She does the most amazing sculptures, beyond anything else you’ve ever seen.”

Works by Gugging artists are currently on show at the Mount Street store, and Kane has used their art in his collection: a smiley face by Heinrich Reisenbauer is woven into a sweater; a watercolour by Johann Korec has been worked into a chiffon column gown. “They’re are free from all inspiration, all innovation, they are just doing things with their hands,” says Kane. “It comes from a real, raw place. To me, that’s true, original art.”

Roksanda’s set. From left: Roksanda Ilincic; director of Tate Galleries Maria Balshaw; illustrator Julie Verhoeven; CEO of Serpentine Galleries Yana Peel; and head of research at Adjaye Associates, Ashley Shaw-Scott Adjaye

Roksanda’s set. From left: Roksanda Ilincic; director of Tate Galleries Maria Balshaw; illustrator Julie Verhoeven; CEO of Serpentine Galleries Yana Peel; and head of research at Adjaye Associates, Ashley Shaw-Scott Adjaye

Roksanda Ilincic is a womenswear designer, who launched her Roksanda label at London Fashion Week in 2005. In 2017, she became a board member of the Royal Academy of Art and the influence of art in her collections has been strongly evident since 2011.

‘Julie Verhoeven changed my belief in colour,” says Roksanda Ilincic, of the illustrator who was her tutor at Central Saint Martins. “She was a vision. She walked through the doors of the classroom and I saw how colour can relate to real life and that it didn’t have to just be a concept. It was the conveying of this medium that brought us together.”

Ilincic’s fashion family has grown since her MA days, and these women – Verhoeven, along with Maria Balshaw, Yana Peel, and Lady Ashley Shaw Scott Adjaye – are at the forefront of the designer’s mind when it comes to her collections. “For me, the true ambassadors of my brand are people like these women,” she says. “As a designer, you are exposed to people in other artistic categories like music, film, literature, art… in some cases, very influential women that are running the art world.”

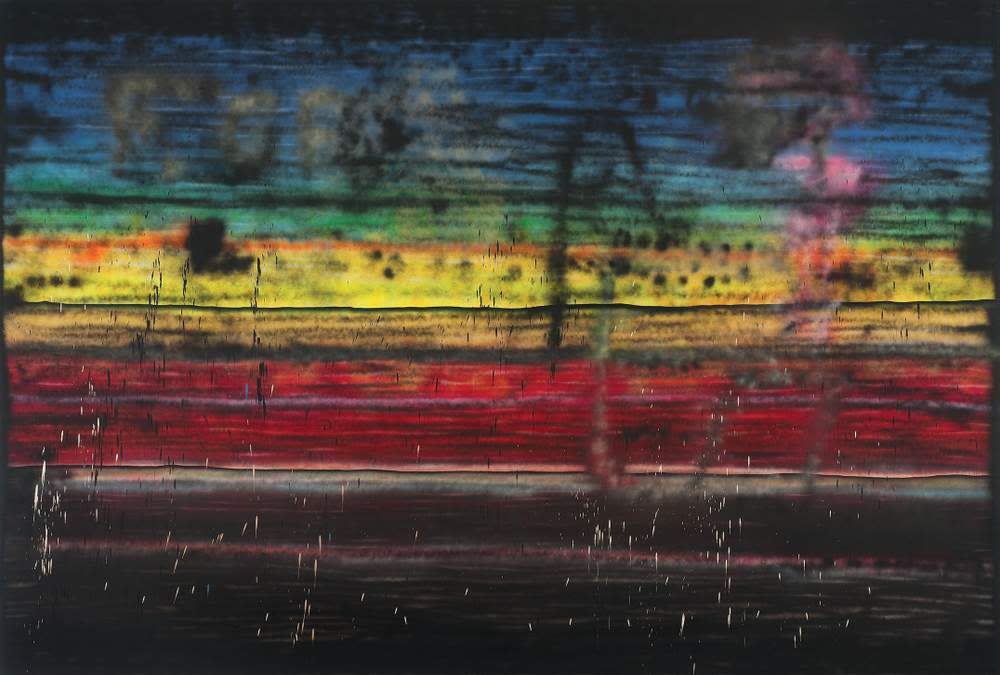

A Rothko-inspired catwalk look from Roksanda AW17

Each season, Ilincic is inspired by a different artist. A trip to the Royal Academy proved fruitful inspiration for AW17, where she found herself in an empty room looking at Rothko’s. “I was alone at an exhibition in front of these artworks... The experience felt so surreal in that moment that I felt I had to dedicate the whole colour palette to those paintings,” she says. “Hence, there is a lot of red... I spend as much time as I can in galleries, it is food for thought.” It’s not the first time Ilincic has reinterpreted artworks. In 2013, she collaborated with the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation on a capsule of eight dresses inspired by Albers’ square. Exhibited in an in-store installation during Frieze Art Fair, they were hung from scaffolding, surrounded by concrete and bricks.

Formerly an architecture student, it’s no surprise that the designer’s friends are so heavily rooted in this artistic sphere. Ilincic was introduced to Balshaw via email, by a friend who insisted they met. “The way these women are changing and influencing our society and are adding incredible things to our culture is so inspiring,” she says. “Their lifestyles and the choices of what they wear is something I’m very aware of.”

There are now more direct artist collaborations with fashion designers than ever, says Ilincic. “When I started to study fashion, maybe art looked down on fashion as a consumer industry,” she says.

“I was always so envious of periods of time when these artists were colliding, but that is happening now in fashion. The time has ripened a mutual respect for all of us… That diversity, coming from many different disciplines, is enriching.”

Having friends so closely linked to other artistic industries is advantageous to her. “Sometimes it is good to step out of fashion. You go back to designing in a completely different direction than if you were stuck in your own world.”

Root out horticultural prints in Arts & Crafts furnishing fabrics says Flora Macdonald Johnston

Just as a set of underlying ideals united architects, designers and artists within the Arts & Crafts movement, so too is fashion collectively minded this season as designers revisit the 19th-century moment that turned the home into a work of art. Bold wallpaper florals and textured silhouettes at Etro are matched at Preen by Thornton Bregazzi and Emilia Wickstead with bloomy designs with cinched waists and puffed sleeves – all lending looks a cosy upholstered feel – while Junya Watanabe pairs heritage brocades and pungently clashing furnishing fabrics with punky tartans and leathers. Chloé’s sleeved shift dress in a muted floral palette recalls William Morris’s wallpaper print Artichoke. At Erdem, a rich yellow velvet evening gown echoed The Demon, a print by the Arts & Crafts architect and designer Charles Voysey. There’s clearly one style to home in on this season.

Mr Christian Dior by René Bouché ©René Bouché

Mr Christian Dior by René Bouché ©René Bouché

With her creative collaborations, designer Maria Grazia Chiuri is continuing the house tradition of looking to art for inspiration

‘Before Mr Dior was a couturier he was a gallerist, so it’s evident that he was obsessed with art,” says Maria Grazia Chiuri of the founder of the house, celebrating its 70th anniversary, of which she is now creative director of womenswear. She is speaking a few days after her AW17 couture show, in part an homage to the designer’s original vision, and in the week Christian Dior, Designer of Dreams opens at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

Friends with Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí, Dior was deeply embedded within the art world, and his six successors have all nurtured similar relationships with the creatives around them. “We were working on the collection at the same time as we were working on the exhibition, and this legacy between Dior and artists became very clear,” says Chiuri of the ways in which she has connected with the house’s founder in her own designs. “He chose living artists who were close to him, and part of his personal life, so I decided to do my runway show with Pietro Ruffo who is a Roman artist.”

Maria Grazia Chiuri ©Brigitte Lacombe.

A new creative director coming into a storied fashion house is invariably faced with the challenge of reinterpreting the brand’s heritage for a modern audience. For Chiuri, who was announced as Dior’s first female designer in May 2016, finding artistic narratives, whether they be tarot embroideries inspired by René Gruau illustrations, or jewels by the sculptor Claude Lalanne, has become an essential way in which to explore the house codes. “Dior is not only about the dress, and the Bar jacket…” explains the Italian designer. “We are working on an idea of the brand to communicate the value of the brand. And so this reference that Mr Dior was an artist and a gallerist is a sign for the house.”

For the AW17 couture show, staged in the garden of the Hôtel des Invalides in Paris, Chiuri commissioned Ruffo to design the set decor, planted with grasses and trees in a star shape, and dotted with sculptures of wooden animals. Branches of the catwalk corresponded to the five continents while an astrological-looking star-shaped work, entitled “L’étoile céleste” was suspended overhead. Chiuri also used it to design a grey silk taffeta dress painted with constellations.

The show’s genesis began in the archive where Chiuri found a 1954 map showing Christian Dior boutiques. When she visited Ruffo in his studio she found him, “working on a map of migration”. The stars aligned. “We’ve always moved around the world,” she says of the theme of global travel that underscored the show, but the journey was more intimate also. “The map print we used on the dress was like a map of memory, my personal map of the Dior archive. A map is not only about places or cities, but also about emotion. I think art, too, can help fashion to have emotion.”

Dior haute couture AW17 ©Dior

Christian Dior’s involvement in the art world was particularly deep. From 1928 to 1934 he ran art galleries in partnership with friends, first Jacques Bonjean then Pierre Colle. “His great idea was to mix famous artists such as Picasso, Braque and Miró, with young talents,” says Florence Muller, fashion historian and co-curator of the exhibition at Musée des Arts Décoratifs. “These included Giacometti, Alexander Calder, Leonor Fini, Jean Cocteau and Salvador Dalí, with whom he became friends. Around 1935, however, Dior found himself in dire financial straits and on the advice of a friend began doing fashion illustration. In 1938, he met artist René Gruau, whom he later commissioned to design the advertising imagery for his perfume, Miss Dior.” He set up his own house in December 1946 (his groundbreaking first collection was shown the following February) and his transformation to couturier was complete. But what co-curator and director of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs Olivier Gabet calls “his painter’s eye” remained.

This sensitivity to art has been a characteristic of all the designers who have followed in Dior’s footsteps, from Marc Bohan and his Pollock-inspired splatters, to John Galliano’s 2007 Bal des Artistes show, and his spirit and passion for art is felt in the house to this day. For Chiuri it’s essential that her artistic associations be authentic. “I don’t think you can just use an artist because they’re an artist. You need to have a connection.” Carola Long

‘Christian Dior, Designer of Dreams’, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, until 7 January, lesartsdecoratifs.fr/en

Self-portrait of me now in a mask by Gillian Wearing, 2011. Collection Mario Testino ©Gillian Wearing, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Self-portrait of me now in a mask by Gillian Wearing, 2011. Collection Mario Testino ©Gillian Wearing, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Can fashion still be avant-garde? From furry shoes to rubber skirts, Charlie Porter finds a stealthily subversive spirit flourishing

What happened to the avant-garde? The question is as relevant for art as it is for fashion. For an artist working today, to be called avant-garde would be naff. Saying that a fashion designer is avant-garde makes them sound old-hat. Yet the definition of avant-garde, of creative acts that are at an experimental forefront, still stands.

Take the fashion house Comme des Garçons. The designs of Rei Kawakubo are at a vanguard, pushing the idea of garments to places not yet understood. Kawakubo has proclaimed her total dedication to “the new”, wanting to create designs that have never before existed. Yet to describe her work as avant-garde would be to do it a disservice. It’s like it removes from the clothing its emotional, real-life charge.

Comme des Garçons AW17

It’s a problem that affects many words connected to past ideas about the future. Modernism today is anything but modern. Perhaps it’s because avant-garde is an idealistic notion, used first in the early 19th century to link art with bold ideas of social and political change. Try being idealistic about anything today: it’s impossible. Our idea of avant-garde is linked to the Surrealists, Dadaists and other radicals of the early 20th century. Photographs of avant-garde artists and their actions are most often in black-and-white. Jean Cocteau; Man Ray; Max Ernst: artists whose work is now a lifetime away.

The designer Elsa Schiaparelli was deeply engaged in the movement. Hats came in the shape of shoes. Buttons were insects or lips. Sweaters had trompe l’oeil collars and bows, taking on surrealist ideas of making things not quite what they seem. She also advanced avant-garde ideas, especially when she collaborated with artist Meret Oppenheim to create a fur-covered bracelet. It was this bracelet that led Oppenheim to make “Object”, her fur-covered cup that is one of the most celebrated works of the movement.

Model wearing a Schiaparelli dress, 1947 ©Horst P Horst/Condé Nast via Getty Images.

Schiaparelli closed her house in 1954, and the brand was dormant for decades. In 2007 it was bought by Tod’s owner Diego Della Valle, who relaunched Schiaparelli as a couture house. Surrealism is still its lynchpin, exclusive is its clientele, but few would call the work of its creative director Bertrand Guyon as avant-garde.

Often, contemporary designers borrow from the world of avant-garde. The present-day manifestation of that Oppenheim fur cup might be the fur-trimmed loafer that has become one of Gucci’s biggest sellers under Alessandro Michele. Japanese label Undercover makes a range of purses in the shape of random objects like cakes, tinned tomatoes and a chick in an egg as part of its core product. Meanwhile, in his new menswear collection for Loewe, Jonathan Anderson showed earrings dangling with mini trumpets. The absurd still appeals to a fashion eye.

But these are just details. Earlier this year, the National Portrait Gallery in London staged the exhibition “Behind the Mask, Another Mask”. It brought together the work of surrealist Claude Cahun with Turner Prize-winner Gillian Wearing, artists born 70 years apart. The work of Cahun, little known until the 1980s, questioned gender and identity. Her work was clearly avant-garde.

In her present day work, Gillian Wearing addresses the same issues. Is she also an avant-garde artist? No, because her work is too connected to reality. Is her work subversive? Yes, with stealth. Maybe this is where the instincts previously described as avant-garde are channelled today: into subversion and transgression.

Sometimes this attitude is stark, like the work of Rick Owens. He is a designer who creates for a parallel universe, one that is frank about its interests in mortality and alternate living. Buy one of this season’s sleeping bag-style dresses at one of his stores, and your till receipt will come in a card printed with an image of Owens blowing his brains out. The safe world of luxury this ain’t.

Balenciaga AW17

At Balenciaga, there is a much more furtive subversion at play. Artistic director Demna Gvasalia has long declared an interest in presenting reality as fashion. It can result in looks that are avant-garde by any other name. His AW17 womenswear show featured a skirt that looks to be made from car footwell mats. The brand caused online uproar when it presented a leather version of the classic Ikea blue shopper for £1,400.

But Gvsalia’s subversion is becoming so stealthy as to be almost imperceptible. At his SS18 collection, he sent out models dressed in purposefully bad tailoring. His inspiration was dads on a day out in the park, and his view of fatherhood is clearly bleak: blazers were oversized, lank, and came complete with creasing at the elbows and at the seat. Gvasalia said it took painstaking work to make them look so real, with weights sewn into the lining to make them hang so depressingly. The result was one of the most remarkable collections of the menswear season.

The point? Today’s avant-garde does not necessarily want to be seen that way. If anything, those at a creative vanguard are now more likely to want to pass as weirdly normal: hence fashion’s ongoing obsession with tracksuits and trainers.

And what of Rick Owens and Rei Kawakubo? Both are masters at creating stealth sellable collections that fund their catwalk radicalism. Commercialism that pays for the uncompromising: perhaps their most avant-garde action yet.